A Year in Constitution-Building: What 2025 Revealed, What 2026 May Bring

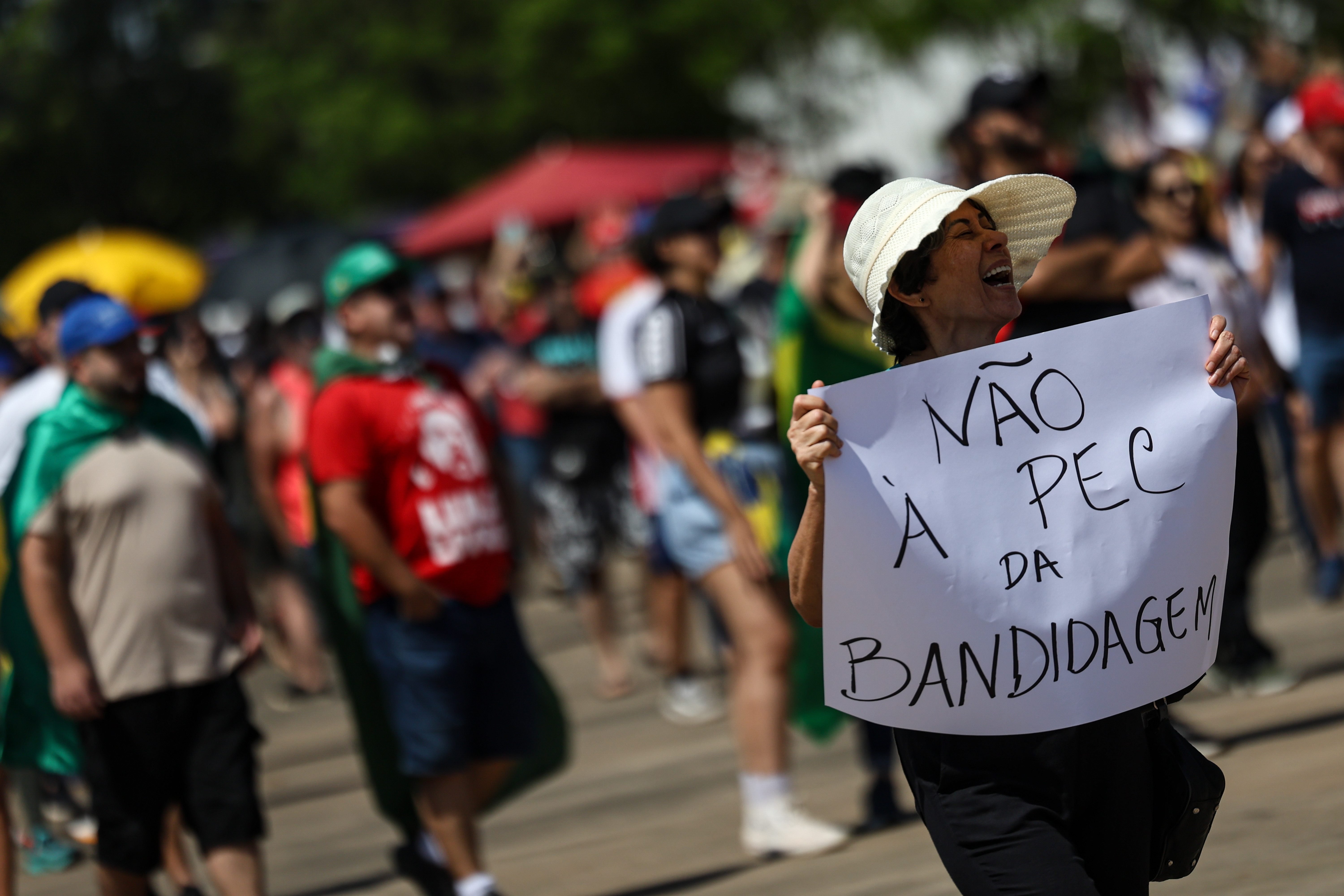

In September, hundreds of thousands of citizens took the streets of Brazil to reject the “PEC da Blindagem”, a proposed constitutional reform to expand parliamentary immunity and limit judicial oversight of lawmakers, ultimately resulting in its unanimous rejection in the Senate. Elsewhere, it is the “Gen-Z” that has sought to drive meaningful change, orchestrating mass protests in countries such as Bangladesh, Madagascar and Nepal in the quest for a more democratic future. Whatever their trigger, these movements demonstrate that, in 2025, people around the world remained actively engaged in resisting democratic backsliding and seeking constitutional change.

However, this year, only one constitution-making process led to the adoption of a new (controversial) constitution (Guinea), and the overwhelming majority of constitutional amendments adopted were driven by anti-democratic actors—aimed to concentrating greater power in the executive, undermine the rule of law, or encroach on human rights—whereas only a handful of countries have passed amendments providing for additional democratic safeguards in their constitutions.

The Constitutional Governance and Rule of Law programme of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) followed these developments closely on ConstitutionNet, the knowledge-sharing hub for the constitution-building community. Through our Voices from the Field series, ConstitutionNet invited local constitutional experts from around the world to analyse the process and content of reforms in their respective countries. In 2025, we published more than 30 original articles on critical ongoing constitutional reform processes. Through these articles, Voices has expanded its coverage to approximately 140 countries since its launch in 2013. In addition, in 2025 our regular news digests brought over 250 updates on news regarding constitutional reform to our readers, to ensure a comprehensive overview of the world of constitution-building in 2025.

The following sections review some notable trends and developments in 2025, before flagging ongoing constitutional reform efforts which will be worth watching closely in 2026.

The Quest for Constitutional Overhauls

In many places around the world, such as Turkey and Venezuela, adopting new constitutions seemed to be high on the political agenda this year. Constitution-making processes, however, fail more often than one might think, and while many countries have embarked in comprehensive overhauls of their constitutional frameworks in 2025, only Guinea was successful in adopting a new constitution, and through a process taking place under a military regime.

Elsewhere, constitution-making processes have stalled or failed. In The Gambia, unresolved disputes over presidential term limits, weakened checks on executive power, perceived lack of inclusive consultation, and persistent political fragmentation led to the failure of a new draft constitution during its second reading in the National Assembly. In Haiti, amid a controversial constitution-making process whose legitimacy was widely questioned, the transitional government decided to abandon its plans to draft a new constitution, while in Ecuador, the proposal to establish a Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution failed during a nationwide referendum. In Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Republika Sprska, progress on a new draft constitution stalled following the revocation of Milorad Dodik’s presidential mandate and uncertainty surrounding the leadership of the entity’s government.

This reflects a troubling pattern worldwide whereby only a minority of large-scale constitution-making processes have succeeded in the last decade, out of which none were truly inclusive.

Consolidating Executive Power

Aside from constitutional replacement, constitutional amendments were primarily used to consolidate executive power and erode checks and balances.

For example, extending the length of presidential terms (Chad, Guinea, Nicaragua, Benin, Zimbabwe), removing presidential term limits (Chad, El Salvador), changing eligibility requirements for presidential candidates (such as requiring candidates in Djibouti to have resided in the country continuously for five years, effectively preventing the opposition in exile to compete), and removing age limits for presidents (Djibouti, Cuba).

In Pakistan, executive dominance was also cemented by granting the President and certain high-ranking military officials lifetime immunity from arrest and civil and criminal proceedings and granting the President control over judicial appointments.

In Nicaragua, in addition to subordinating the judiciary and legislature to the executive branch and eliminating checks and balances, the establishment of a co-presidency opened the door for former Vice President and wife of President Ortega to be designated co-President.

Djibouti also removed the requirement that new constitutions be submitted to a referendum to be registered and published, effectively strengthening the ability of the executive and its parliamentary majority to steer controversial constitutional changes without popular approval.

Attacking the Rule of Law

Constitutional reforms in 2025 have also put the rule of law under increasing pressure.

In Hungary, the 14th Amendment removed the rule that the prosecutor general must be selected from the ranks of career prosecutors, opening the position to political appointees. It also increased the minimum age for appointing new judges and altered professional eligibility criteria in ways that favoured candidates from outside the current judiciary, a change widely interpreted as facilitating the appointment of government allies. Additionally, the amendment allowed judges to stay in office until age 70 instead of retiring at 65, a set of reforms broadly regarded as strengthening political control over Hungary’s judicial system.

Pakistan’s 27th Amendment, passed through one of the fastest and most controversial processes in its recent history, introduced reforms widely seen as weakening judicial independence. Most notably, it created a Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) whose chief justice and initial judges are appointed by the executive, heightening concerns about political influence over a court newly invested with exclusive authority over constitutional interpretation and fundamental rights. Future appointments will be made through the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP) now dominated by executive and political actors after the 26th Amendment. The amendment also raises the retirement age for executive-appointed FCC judges from 65 (the limit for supreme court judges) to 68 and allows for the transfer of high court judges without their consent on the recommendation of the executive-led JCP.

In Brazil, the so-called “Shielding Constitutional Amendment” (“PEC da Blindagem”) was introduced to expand parliamentary immunity and limit judicial oversight of lawmakers, but—as mentioned above—was ultimately rejected following widespread nationwide protests, underscoring the impact of civic engagement in defending the rule of law.

In Italy, a constitutional amendment separating the functions of judges and public prosecutors, currently united in a single body, will move to a nationwide referendum expected in spring 2026. While the reform was purportedly introduced to strengthen the impartiality and transparency of Italy’s judicial system, many have raised concerns about threats to prosecutorial independence and autonomy.

In Malta, most provisions of a constitutional bill attempting address its inefficient justice system failed due to lack of bipartisan support. While one measure passed, creating a body to investigate complaints against members of the judiciary, scrutinize their assets, and inquire into judicial delays, a lack of clarity regarding the scope of this new role suggests that significant shortcomings in Malta’s court system remain unresolved.

Against a backdrop of global rule-of-law regression, some countries have recently adopted proactive measures to protect their judiciaries from future democratic backsliding (Norway, Germany). In 2025, Sweden introduced constitutional amendments to strengthen the independence of its judiciary, which received broad public support. The final parliamentary vote on the proposed amendments (which also includes controversial changes on Sweden’s constitutional amendment procedure) is expected to take place following the 2026 general elections.

Undermining Human Rights

Alongside continued rule of law regression, human rights and fundamental freedoms were once again under significant strain throughout 2025.

Hungary and Slovakia both adopted constitutional amendments enshrining a strictly binary definition of sex in the Constitution, while in Monaco, in a rare occurrence, Prince Albert II refused to sign a constitutional bill legalising abortion despite the proposal passing with a large majority in Parliament. In Hungary, the 15th Amendment afforded children’s rights precedence over other fundamental rights, except the right to life, which effectively provided a constitutional basis for the government to ban the Pride March, while Slovakia introduced a controversial provision affording Slovak law precedence over European Union law in matters of “national identity”. In Kyrgyzstan, while ruled unconstitutional, a proposal to reinstate the death penalty for certain crimes left civil society in fear that similar proposals could be reinstated and used to further shrink civic space and crackdown on dissent.

Many countries have also proposed constitutional amendments undermining citizenship rights (Vanuatu, Sweden, Estonia, Russia). In Hungary, the 15th Amendment introduced a vague and unprecedented provision allowing for the “suspension” of Hungarian nationality for dual citizens. Two months later, Hungary’s Citizenship Act was amended to describe the procedure for citizenship suspension of naturalized dual citizens “deemed to pose a threat to public order, public, or national security.” In Cambodia, the Cambodian People’s Party passed a constitutional amendment removing the long-standing prohibition on the revocation of citizenship, instead leaving it to be “determined by law.’’ In both cases, the amendments raise concerns about their potential to silence political opponents and critics and create a chilling effect on dissenting voices, especially given the lack of judicial independence and adequate legal safeguards in both countries.

Given these global developments, it is unsurprising that fears of fundamental rights regression contributed significantly to the failure of Ecuador’s constitutional referendum.

On the brighter side, in Cyprus, a new constitutional right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment was adopted, including a positive state obligation to protect the environment, and procedural guarantees such as access to information, justice, and effective remedies. While its potential to apply to public and private actors alike remains uncertain, this certainly represents a positive step towards environmental protection in the country. In Malta, a similar constitutional amendment proposal failed to pass in Parliament.

Reforming the Legislative Branch

2025 also saw many countries embarking on reforms to their legislative branch.

While Belgium decided to abolish its Senate following decades of institutional erosion and Kazakhstan announced the start of comprehensive parliamentary reforms and a potential shift towards a unicameral parliament, Benin approved a major constitutional reform establishing a new 25-member senate, including members appointed by the President, and New Zealand is proposing to extend the country’s maximum parliamentary term from three to four years. Further, Malaysia passed a constitutional amendment bill to strengthen the independence of its legislature by revising key constitutional provisions on parliamentary leadership and administration.

Zambia also enacted a far-reaching constitutional amendment bill which, among other changes, expanded and restructured its National Assembly by increasing the number of elected seats, introduced a mixed-member proportional system to widen representation, and revised rules on nominations, by-elections, and parliamentary terms.

Finally, a number of countries have proposed reforms aimed at achieving gender parity or introducing gender quotas in their parliaments (Belgium, Kenya, Nigeria, Kyrgyzstan).

Between Transition and Continuity: on the Horizon for 2026

In 2025, some countries entered periods of political transition while others laid the groundwork for significant constitutional reforms, with several set to unfold in 2026.

Syria signed a constitutional declaration setting a five-year transitional period in March and held parliamentary elections in October—a first step toward stabilization and reform. Yet, it is still uncertain whether the newly formed parliament can live up to the high expectations as it takes on the critical responsibility of drafting a new permanent constitution for Syria.

In Bangladesh, Madagascar, and Nepal, the Gen-Z took to the streets demanding a more democratic future, leading to the fall of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, President Andry Rajoelina, and Prime Minister K. P. Sharma Oli and marking a period of political transition in each country. In Madagascar, the military-led transitional government has announced national consultations in 2026, followed by legislative and electoral reforms, a constitutional referendum in early 2027, and presidential elections thereafter. Bangladesh’s July Charter, endorsed by 24 political parties, bundles over 80 reform proposals, around half requiring constitutional amendment. Persistent disagreements among parties cast uncertainty over the referendum set alongside the February 2026 general elections, leaving broad consensus in doubt. In Nepal, the government signed a roadmap with Gen-Z leaders, pledging a Constitutional Amendment Recommendation Commission to review the Constitution, consult the public, and propose key reforms.

2025 also saw the appointment of several constitutional review bodies (Ghana, Turkey, Palestine, Venezuela). Simultaneously, ongoing reviews stalled in Barbados, which is yet to act on the 2024 recommendations of the Constitutional Reform Commission, continued to unfold in Armenia, Nigeria and the British Virgin Islands, and resumed in Saint Lucia. In South Sudan, the Presidency has announced plans to establish a committee to amend key provisions of the Transitional Constitution in a push to deliver national elections in 2026.

As we step into 2026, we will likely see the next phase of constitutional reform after completion of constitutional review in Ghana. We also anticipate ongoing debates and the possibility of significant constitutional reforms in countries such as Niger and Senegal, which recently held national conferences to produce recommendations as a foundation for constitutional changes, as well as Fiji and Sri Lanka. Elsewhere, constitutional referendums are on the horizon (Zambia, Bangladesh, Armenia, Italy, Madagascar) and will test whether constitutional reform can still be driven by popular will.

Whether any of these processes will culminate in the adoption of new constitutions and democratic consolidation, result in new forms of democratic backsliding or simply dissolve into stalled ambitions and unfinished reforms, remains to be seen. Through ConstitutionNet, we will continue to deliver timely updates and original analyses of these developments in 2026, tracking constitutional reform processes as they unfold globally.

As we start 2026, International IDEA’s Constitutional Governance and Rule of Law team would like to thank our readers for their continued engagement and interest in the world of constitution-building.

About the Author

Alexandra Oancea is the Editor of ConstitutionNet and Associate Programme Officer for the Constitutional Governance and Rule of Law Programme at International IDEA.

Suggested Citation

Alexandra Oancea, ‘A Year in Constitution-Building: What 2025 Revealed, What 2026 May Bring’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 8 January 2026, https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/year-constitution-building-what-2025-revealed-what-2026-may-bring

Contribute to Voices from the Field

If you are interested in contributing a Voices from the Field piece on constitutional change in your country, please contact us at constitutionnet@idea.int.