Constitution building in 2017 through the lens of ConstitutionNet’s Voices from the Field

Introduction

Constitution building is often described as unfolding in ‘waves’. Nevertheless, the number of constitutional reform processes happening in any given year reflects the fact that it has become a ‘permanent’ feature of global constitutional developments. Following on the trend in the last years, 2017 witnessed its share of constitutional reform efforts in virtually every corner of the world. The Constitution-Building Programme of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) has been reporting on these developments through its dedicated platform, ConstitutionNet. In particular, the Voices from the Field series has given local experts a unique medium to provide detailed accounts of the background, process, actors, contentious substantive issues, and the prospects in the constitutional reform processes in their respective countries. In this end of year editorial, we look back at some of the core issues in terms of both process and substance.

A notable experiment in terms of constitutional reform process in 2017 was the resort to ‘Deliberative Polling’ in Mongolia.

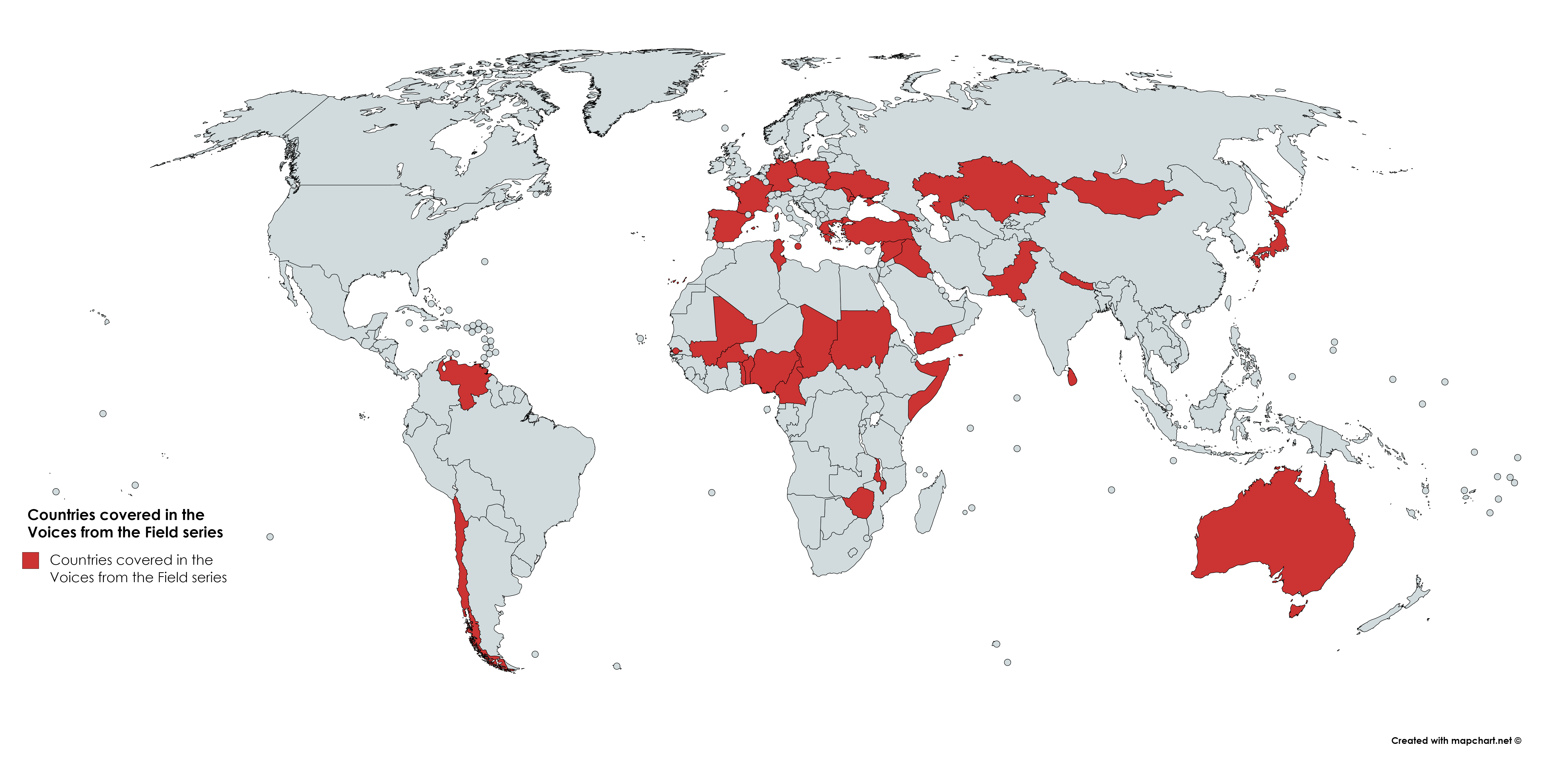

In 2017, ConstitutionNet published 44 original Voices from the Field spanning constitutional reform projects in 35 countries from all parts of the globe: from Africa (12 countries), to Asia (seven countries), to Europe (10 countries), to the Middle East and North Africa (four countries), and to Latin America (two country). Seventeen of these countries were covered in the 2017 Voices from the Field series for the first time. The number of countries covered constitutes almost one in five of the membership of the United Nations. Remarkably, this number does not include the full list of countries undergoing constitutional reforms as reflected in ConstitutionNet’s daily updates (such as Ecuador and Guyana in Latin America, the Bahamas in the Caribbean, Libya in the Middle East, Ireland in Europe, the Philippines in Asia, and Mauritania and Burundi in Africa). Few of the reform processes were finalized (e.g. Georgia, Turkey), some have stalled (e.g. Mali), some have been rejected (e.g. Australia, Benin) and, in most others, the process continues (e.g. Chile, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, and Venezuela).

A significant number of constitutional reform efforts do not succeed.

Perhaps the most notable experiment in terms of constitutional reform process in 2017 was the resort to ‘Deliberative Polling’ in Mongolia. The establishment of a constituent assembly in Venezuela also raised issues regarding the conditions of formation of such assemblies and the rules for their composition and working procedures. Issues of group identity and the management of diversity were prominent throughout the year from Spain to Australia to Cameroon to Sri Lanka. Another crucial area of constitutional reform efforts has been the composition and mandate of institutions checking the exercise of power by the political institutions (courts and prosecution services), which were the focus of reforms from Zimbabwe to Ukraine to Poland to Mongolia to Malta. Other recurring substantive issues included gender inclusion (Benin, Nigeria), reforms towards more proportional electoral systems for legislatures in local and regional elections (Tunisia) and for the national legislature (France, Greece), changes away from the first-past-the-post electoral system for the presidency (Malawi, Togo), as well as shifts in the system of government (Sri Lanka, Turkey).

Stalled constitutional reform process

Before discussing the principal issues that arose in constitutional reform processes in 2017, it is important to note that not all reform efforts that started before 2017 have been finalized. In fact, a number of processes have stalled. In Sierra Leone, the government has officially rejected the overwhelming majority of the recommendations of the Constitutional Review Committee, which were developed following extensive public engagement. Despite pressure from civil society organizations, the constitutional reform process in Tanzania does not appear to be a government priority. The legislative consideration of constitutional amendment propositions of the Liberian Constitutional Review Committee has also stalled. With a new president expected to take over following the run-off elections planned for 26 December 2017, the reform process is unlikely to take center stage. Despite repeated expressions of interest, the Zambian government is yet to reinvigorate the constitutional reform in response to the rejection of proposed reforms in a referendum in 2016. Similarly, in Yemen, the constitution reform process did not produce a final constitution. With the ongoing peace and transitional efforts taking center stage, the fate of the constitutional reform process is uncertain. While the constitutional reform processes in Libya and Burkina Faso have made some progress, the outcome of the processes is unclear at best.

Despite the significant number of constitutional reform efforts that do not succeed, the causes, consequences and lessons of these efforts are underexplored. The Constitution-Building Programme of International IDEA plans to undertake initiatives to understand these efforts better.

New modalities of public involvement in constitution building processes

Beyond the traditional focus on the content of constitutions, the idea of an open, inclusive and participatory constitution making process has taken root, particularly in the context of the making of new constitutions or significant amendments. Constitutions are no longer the exclusive domain of political institutions and actors and experts. Active popular participation and input is recognized as the foundation for claims of popular authorship of constitutions, reflected in the much touted, ‘We, the people …’. Nevertheless, the exact modality of participatory constitution making is still an evolving notion. While such processes have taken the form of constituent assemblies (Venezuela, Nepal) and large-scale public consultations, particularly in conflict-affected settings (South Africa, Kenya), but also in stable democracies (Chile), new models of popular participation have emerged.

In Iceland and Ireland, constitution makers have experimented with ‘constitutional conventions’ /’citizen assemblies’ where ordinary people from all sensibilities are brought together to deliberate upon and decide on profound constitutional issues. The latest Irish Citizen’s Assembly, established in 2016, which included randomly selected citizens but also representatives of political parties, discussed and finalized recommendations on the controversial issue of abortion. The Assembly has adopted its report, which is awaiting approval in the legislature and in a referendum, which is expected to be held in 2018.

The new models of public participation allow ordinary people (mini-publics) not only to discuss and propose constitutional solutions, but also to influence the drafting of the text of the constitution.

Mongolia has also employed ‘Deliberative Polling’ in constitutional reform where a randomly selected group of people met over a period to deliberate upon and pass recommendations on a range of constitutional reform issues. The process allowed the participants to review and even reject proposals from prominent political parties. Remarkably, the Mongolian Parliament has amended the relevant laws to make Deliberative Polling a formal requirement in all future constitutional amendment processes. In both Ireland and Iceland, the resort to citizen assemblies has not been formalized, although in Ireland it may now be considered as a conventional part of the amendment process, at least in relation to socially controversial subjects.

While there may be differences in their nomenclature and exact composition, the above innovations allow ordinary people (mini-publics) not only to discuss and propose constitutional solutions, but also to influence the drafting of the text of the constitution, a traditionally technocratic exercise even in participatory constitution making processes. As these new models of participation become more prominent, including possibly in Chile, their relative value as well as lessons regarding their optimal composition, their agenda-setting power, scope of their mandate, working procedures, as well as the practical aspects (such as timing and cost) requires further study.

So far, while the constitutional convention in Iceland had an open mandate and considered a wide range of constitutional issues, in Ireland and Mongolia, their mandate was largely limited to specific and predetermined constitutional issues. The particular value of and challenges of resorting to them in processes of making new constitutions is less understood.

Moreover, in all the three cases, the outcomes of the participatory processes were subject to the approval of the political institutions and, in Ireland, also to a referendum. In Ireland, only a handful of the recommendations have been put to a referendum, and in Iceland, politicians have largely abandoned the reform project and the draft constitution was never approved in parliament or presented for final popular approval, although the proposals were well received in a consultative referendum. The interaction of these ‘mini-publics’ with traditional procedures involved in constitutional amendment processes needs further investigation. In particular, the manner of approval of the outcomes of such processes, i.e. whether existing political institutions should have the authority to adopt or modify the proposals, or whether the proposals should be directly submitted to a referendum should be explored.

Group identity continues to be a critical driver of political mobilization.

Moreover, citizen assemblies have principally been employed in constitutional reform processes in small and stable democracies. Their potential and relative utility in larger countries, and in conflict-affected contexts and in transitions from authoritarianism and political instability remains untested.

To contribute to knowledge and practical lessons in relation to citizen assemblies, the Constitution-Building Programme of International IDEA plans to organize activities in 2018 and beyond.

The constitutional management of diversity and gender

Group identity continues to be a critical driver of political mobilization. Identity-based claims are mainly driven by members of minority groups, whether ethnic, religious, linguistic, or indigenous groups. Beyond the stalled secession drive in Catalonia, which has nonetheless triggered a constitutional reform process, minority groups from around the world have sought constitutional reforms usually in the form of increased territorial decentralization of authority (Sri Lanka, Mali), fiscal powers (Spain), and in some cases specifically federalism (Chad). The Australian case is unique in the sense that it focused on demands of indigenous peoples, who live dispersed across the country, for a ‘Voice’ through an advisory body in the national legislative process, rather than territory based decentralization of power.

While the level of success of minority groups in each country varies, demands for autonomy, both territorial and non-territorial, are likely to pose continuous challenge to centralized models of governance in plural societies. Constitutional frameworks are vital to these demands. The refinement of mechanisms of constitutional accommodation of identity-based claims should therefore continue to occupy constitutional practitioners and theorists alike.

The issue of gender and the political representation of women was also discussed in Tunisia, Nigeria, Malta and Benin. While changes to the electoral law in Tunisia resulted in better representation for women in local and regional political institutions, in Nigeria, the reforms for the representation of women in the national legislature and executive were rejected. In Benin, parliament rejected all the proposals for constitutional reform, which included provisions for better gender representation. The reform process in Malta is still at an early stage.

Reforms targeting courts and ‘fourth’ branch institutions

Constitutional courts have been recognized as critical institutions in modern constitutional thought. This is reflected in their formal empowerment to decide on issues hitherto domains of the political institutions. Constitutional courts have also increasingly become consequential in constraining and legitimizing the exercising of government power. This is why they are often targets of constitutional reforms, as evidenced in the reforms in 2017. Indeed, in the case of Poland, the ruling party has pushed for a number of reforms that could undermine the independence and effectiveness not only of the constitutional court but also other regular courts.

Some of the reforms aimed at enhancing the accessibility, independence or effectiveness of courts. For instance, the reforms in Ukraine require a more transparent and competitive process in the appointment of judges to the constitutional court. In Mongolia, the reforms aimed at empowering the legislature vis-à-vis a weakened presidency in the process of appointment of the highest judges. The reforms in Georgia shifted the power of nomination from the president to the judicial council. The attempted reforms in Benin would similarly have reduced the involvement of the political actors in the appointment of constitutional court judges, although they would at the same time have reduced the court’s powers over the validity of elections. In contrast, in Zimbabwe, the first amendment to the 2013 Constitution has enhanced the authority of the President in appointing the highest judges thereby reversing some of the gains in the recent constitution. While most of the reforms related to the composition of constitutional courts, the reforms in Kazakhstan empowered the constitutional court to review proposed constitutional amendments and to provide advisory opinions at the request of the president of the country. Moreover, the president no longer has the power to veto decisions of the court.

Reforms towards enhancing the independence and impartiality of the prosecution service should attract enhanced engagement.

The reforms affecting courts necessitate continued discussion on enhancing the independence and impartiality and accountability of judges, as well as in terms of protecting gains of inclusive reform processes in establishing independent institutions.

Related reforms in Malta aim at enhancing the independence and impartiality of the prosecution services and the police commissioner, who are currently appointed by the prime minister. The main proposal is to require the approval of candidates selected by the prime minster with a two-third legislative majority, which will enhance cross-party consensus in a de fact two-party system. Appointment mechanisms that reduce the involvement and role of the political institutions have also been proposed. Similarly, the proposed amendment to the Bahaman constitution would separate the prosecution services from the political office of the attorney general. While the constitutional building community is usually focused on the design of the courts, considering their importance, the reforms towards enhancing the independence and impartiality of the prosecution service should attract comparable engagement.

Systems of government and electoral systems

Some of the constitutional reform efforts were related to changes to the system of government. The Turkish constitutional referendum, one of the few in 2017, saw the finalization of the process of formalizing the shift from a parliamentary to a presidential system. In Mali, the proposed amendments would greatly undercut the powers of the prime minster, largely shifting from a semi-presidential toward a de facto presidential system. Georgia approved constitutional amendments finalizing the shift from a semi-presidential to a parliamentary system. Sri Lanka is mulling a similar move. The shifts in Georgia and Sri Lanka reverse the more common transition from parliamentary to presidential systems. This calls for the triggers and potential consequences of these transitions, and the related constitutional reforms such transitions may necessitate or entail.

The shifts in Georgia and Sri Lanka reverse the more common transition from parliamentary to presidential systems.

There were also reform efforts aimed at electoral systems for the head of state (Malawi, Togo) particularly to require a 50%+1 majority for the election of presidents, as well as for parliament (France, Greece) towards adopting a more proportional electoral system. Tunisia also implemented a new electoral law for local and regional elections, which particularly aimed at enhancing the presentation of women and the youth.

Concluding remarks: 2018 prospects

Constitutions largely reflect power relations and compromises at the time of their making. As the power balance shifts, the pressure for reform rises. In this context, constitutional reforms will continue to be prominent features of politics. In 2017, the constitutional reform drive showed no sign of slowing down. Constitutional politics are also likely to dominate 2018 in countries around the world, from Spain to Sri Lanka, The Gambia to Tuvalu, Mongolia to Venezuela, and from South Sudan to Ukraine. The Constitution-Building Programme of International IDEA and ConstitutionNet will continue to provide regular updates and original analysis to make sense of the multifaceted interaction of actors, context, processes and substantive issues, and to provide comparative lessons for national and international practitioners, policy makers and other actors involved in undertaking or assisting constitution reform processes worldwide.

Until then, we wish our readers a wonderful holiday season.

Adem K Abebe is the editor of ConstitutionNet.