Introduction

The Arab Republic of Egypt is a transcontinental nation on the northeast of Africa and the southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. The Republic lies between Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Gaza Strip and Israel to the northeast, the Red Sea to the east, Sudan to the south and Libya to the west. Covering over 1,001,450 square kilometers, Egypt is home to more than 85.2 million people making it the world’s fifteenth most populated nation. The great majority of the population lives in the arable land found in the banks of the Nile River. Cairo, the capital city and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, is home to over eleven million people. Approximately 90% of the populace is Muslim and 99.6% are ethnic Egyptian.

Snapshot: Egypt’s Post-Mubarak Constitution making

|

|

English |

Arabic |

Commentary |

|

Constitution |

Link | ||

|

Draft Constitution by the 50 member committee (C50) |

|

||

|

The 50 member committee’s rules of procedure |

|

||

|

The presidential decree establishing a 50 member committee to prepare a final version of the draft constitution |

|

||

|

The proposed changes to the 2012 Constitution |

|||

|

The Constitutional Declaration suspending the 2012 constitution and establishing a new road map for the country |

|||

|

The 2012 Constitution |

|||

|

Draft Fundamental Principles Document |

|||

|

The March 2011 Constitutional Declaration |

Constitutional history of Egypt

The 1923 Constitution

The constitutional history of modern Egypt can be traced back to the Egyptian revolution of 1919. Following rising agitations against Britain, which had governed the territory as a protectorate since 1914, and increasing demands for independence, British rule over the territory was formally terminated under the terms of a joint declaration between Britain and Egypt in 1922. This declaration provided for the establishment of a 30 member legislative committee, made up of political parties and members of the revolutionary movement, with the responsibility to draft a constitution for an independent Egypt. Promulgated in 1923 the Constitution established a constitutional monarchy with the King as the head of the executive. The 1923 Constitution enshrined many personal freedoms and liberties; such as a mandate for primary education, privacy of the house, property, and telephone. The 1923 Constitution created a bicameral parliament with powers to convene itself in case it was not called into session in accordance with the schedule. This Constitution has served as the model for all Egyptian constitutions that have followed. The 1923 Constitution gave much power to the king but sought to a limited extent to empower the people.

Although a step in the right direction towards democratization, the 1923 Constitution still had many problems. First the King could single-handedly disband parliament, appoint up to two-fifths of the Senate, and veto parliament bills. The Constitution protected the king’s image and gave him power to ratify laws. Furthermore, successive kings frequently ignored or violated the Constitution. The Constitution also does not mention women, except once: requiring primary education for boys and girls. Exceptions, conditions, and qualifications within the Constitution made it easy for the government to infringe on the personal liberties listed in the constitution. Intermittent interference by the British into Egypt’s politics and policy making also hindered the Egypt’s march towards democratization. A new constitution promulgated in 1930 briefly replaced the 1923 constitution for five years. This new Constitution, unlike the 1923 Constitution that enfranchised all adult males, limited the franchise to those owning a certain amount of property.

In 1952 a Free Officers’ Revolution abolished the constitutional monarchy and set up a republic under a new constitution.

The 1952 Constitution and Developments between 1952 and 1971

Adopted following the abolishment of the constitutional monarchy, the 1952 Constitution transformed Egypt into a republic ruled by elements of the military, who were responsible for the 1952 revolt. Because of the domination of the political sphere by the military, through the Revolutionary Command Council, the period between 1952 and 1970 were characterized by an erratic constitutional development. This period saw the military constantly issuing and revoking constitutional edicts that were at best self-serving and hindered the development of any effective multiparty democracy that the 1952 revolution was designed to accomplish. Accordingly, three constitutions would be issued and repealed in the twenty years in between. The first was the Constitution of 16 January 1956. The Second was the Unity Constitution of 1958, following the creation of the United Arab Republic of Egypt and Syria, and the third was the Interim Constitution of 25 March 1964, issued following the dissolution of the Egypt-Syria union. This Constitution remained in place until a new one was promulgated in September 1971.

The Constitution of 11 September 1971

This Constitution remained in force - with few amendments in 1980, 2005 and 2007 – until its dissolution in February 2011. It stipulated four main goals: world peace, Arab unity, national development and freedom of humanity and all Egyptians. The 1980 amendment is significant for having made Sh’ria (Islamic law) the basis of all laws. This differs from previous constitutions that were secular in nature and did not require laws to conform to principles of Islamic law. Article of the 1971 Constitution however, declared Islam the state religion and Arabic its official language. Article 2 also establishes the principles of Islamic Shri’a as a main source of legislation. A 1980 amendment changed the article to declare Shri’a as the main source of legislation. Under Mubarak the Supreme Court read article 2 narrowly, displeasing certain Islamic factions.

In addition, the 1971 Constitution established a multi-party, semi-presidential system of government with a strong executive authority on the one hand, and a legislative and a judicial authority on the other hand. However, significant restrictions on political activities effectively made Egypt a one party state. The Constitution subjugated political parties to the law and the government could control who could for a party and in which elections they could participate. For example, in 2007 Mubarak regime passed amendments to the Constitution, prohibiting the formation of political parties based on race, religion, or ethnicity. The amendments were put to a popular referendum and, despite low voter turnout and boycott by opposition groups, passed with 75.9% approval. This sowed the seeds of deep resentment against the system that would eventually explode in the popular revolts on 25th of January 2011, spurred by similar events in Tunisia.

Subsequent amendments to the 1971 Constitution increased the power of the executive and abolished the two term limits. A 2007 amendment to article 179 allowed the president to transfer any defendant to any court crimson charges of terrorism.

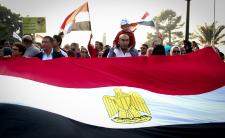

Constitutional and political developments in the post Mubarak era

Following a two week long people revolt between 25 January and 11 February 2011 that saw the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces took over the state, dissolved state institutions, suspended the Constitution and announced the establishment of an eight man constitutional committee (there were no women appointed) - with a ten day deadline - to prepare a technical report to review certain articles of the Constitution. A referendum, on March 19, 2011, approved the draft proposed by the Committee ratified. This was followed by parliamentary and presidential elections in January and May of 2012, respectively. Both elections saw the emergence of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, as the dominant political force in Egypt, winning 70% of the seats in parliament and while their presidential candidate Mohammed Morsi won the presidency. It was also the first time an Islamist had been elected to the presidency.

Once installed, the new parliament had the responsibility to prepare a more permanent Constitution for Egypt. Parliament's main role was to establish a representative constituent assembly composed of both MPs and others outside the parliament to drive the process. A constitution declaration issued on March 30, 2011 required the formation of a hundred-member Constituent Assembly within six months, to draft a new constitution. The process, however, took almost a year because as stakeholders could not agree on its composition. Eventually, 100 hundred member assembly mostly dominated by the Islamists drawn from the FJP dominated parliament was established provoking public outrage. The assembly was criticized for want of diversity and representativeness. The body was constantly under legal challenges seeking to dissolve it as it worked on the constitution. Christians continued to complain about the distribution of seats, and most of their representatives boycotted. In October 2012, the assembly announced that it had completed the first constitutional draft. A public awareness campaign followed to educate the public on the constitution. The assembly finalized the drafting process on November 29, 2012.

As more legal challenges were mounted against the body, and the Supreme Constitutional Court accepted to review the cases brought against it, President Morsi as part of a process bent on consolidating his power issued a new constitutional declaration on November 22, 2012 which amongst others prohibited- pending the completion of a permanent constitution – any judicial challenge to his decisions. This effectively barred any form of judicial review of the constituent assembly which had been established with Morsi’s support. This decision paved the way for the assembly’s draft to go to referendum. In December 2012, the draft was adopted in a public vote. Many people though criticized the document as lacking popular ownership giving the rushed and closed process through which it was developed.

The 2012 Constitution strengthened the role of Islam in the legislative and judicial process. It made Shari’a the principle sources of Egyptian law. The constitution defined those principles as "evidence, rules, jurisprudence and sources" accepted by Sunni Islam.

Constitutional challenges under Morsi Regime

Egypt’s new 2012 Constitution lasted for approximately six months. Many segments of the society resisted the increasing hold of the FJP on the state and Morsi’s consolidation of executive powers. He argued that it was necessary to ensure the transition of the country and the implementation of the Constitution. This resistance eventually took violent forms with regular clashes between Islamists and secularists. During the anniversary of the revolution against Mubarak on 25 January 2013, clashes erupted between pro and anti Morsi supporters. Violence between the various groups continued as the society increasingly became divided between the ruling Islamists and the secularists who resisted their rule. Events escalated on 30th June as millions took to the street demanding Morsi’s resignation. On 1 July 2013, the military gave the pro-Morsi and anti-Morsi faction 48 hours to reach a solution or face military intervention. Following the former’s inability to find a political solution, the military deposed Morsi on July 3, 2013, suspended the Constitution and set up an interim government headed by the Supreme Constitutional Court President, Adli Mansour.

Five days after taking office on 8 July, President Mansour issued a new Constitutional Declaration outlining a new transition process and interim governing structures. The Declaration granted Mansour legislative and executive powers—which Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood had sought all along. It granted the Interim President the powers to appoint and dismiss ministers. In addition, it reserved 50% of parliamentary seats to farmers and workers. Amongst many other rights, the Declaration recognised the right to free speech but only to the extent allowed by law. Article 10 granted freedom of assembly under certain conditions, but remained silent on the specifics of those conditions.

In terms of the process for writing a new Constitution, the declaration provided for the creation of a ten member-committee (C-10) comprised of six top judges and four constitutional lawyers to write a new constitution. As a matter of fact, the C-10 was not expected to write a completely new constitution but rather to review specific articles of the 2012 Constitution and propose amendments.

The (C-10) finished this task in August 2013 and submitted a draft to a 50- member committee (C-50), which was comprised of the major components of the Egyptian society: women, military, youth etc. According to the constitutional declaration, the C-50 was to produce the final draft of the constitution having then two months of public consultation. From the outset, the C-50 announced it would not limit itself to the clauses and subjects specified in the C-10’s draft but would add additional changes to the Morsi Constitution.

In December 2013 the passed-50 released a final draft which was approved in a referendum by 98.1% of voters in January 2014. Significant among the reforms in the new Constitution was the strengthened role of the security sector, in particular, the army and the police as well as the judiciary.

Structure of Government under the 2014 new Constitution

Executive branch

The President is the Head of State, the Chief of the Executive Authority, and the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. He is elected by a direct vote for a term of four years and is re-eligible once. The President does have some duties relating to the legislative function of government, including the promulgation of statutes, the vetoing of bills, and the ratification of treaties. Any candidate for President must be Egyptian, born to Egyptian parents, married to an Egyptian and hold only Egyptian citizenship. A candidate must also receive the recommendation of at least 20 elected members of the House of Representatives, or endorsements from at least 25000 citizens of voting eligibility in at least 15 governorates, with a minimum of 1000 endorsements from each governorate.

The President appoints the Prime Minister, who in turn forms the cabinet. The cabinet consists of the Prime Minister, his/her deputies and ministers. Although the President holds the title of Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, he may not declare war, or send the Armed Forces outside State territory, except after consultation with the National Defence Council and the approval of the House of Representatives with a majority of its members.

Legislative branch

The Constitution vests legislative power in a single chamber the House of Representatives. The House is composed of no less than 450 members elected by direct, secret public vote for a five year term. The President of the Republic may appoint a number of members that does not exceed 5%.

The House of Representatives has the right to impeach the president if he breaches the provisions of the Constitution. It also approves the national budget, which is put to vote on a chapter-by-chapter basis.

Judicial branch

The Constitution sets up an independent judiciary that manages its own affairs and those of its members. It comprises the Supreme Constitutional Court, the Administrative Prosecution, and the State Council. The President of the Republic or Parliament presents draft laws governing presidential, legislative or local elections to the Supreme Constitutional Court, to determine their compliance with the Constitution prior to dissemination. The Supreme Constitutional Court consists of a president and a sufficient number of deputies to the president. The Constitution also establishes a Court of Cassation with jurisdiction over the validity of membership in the House of Representatives.

Structure of Government

Timeline of constitutional developments in Egypt: 1923-2011

| 1919 | Popular revolts lead to end of British Protectorate |

| April 1923 | Independence Constitution promulgated and Egypt becomes a constitutional monarchy |

| 1930 | Constitution of 1923 replaced with 1930 Constitution |

| 1935 | Constitution of 1923 restored |

| 1952 | Free Officer’s Revolution overthrows the constitutional monarchy |

| January 1956 | New Constitution adopted |

| 1958 | Unity constitution adopted following Union with Syria |

| March 1964 | Interim Constitution issued following the dissolution of the Egypt-Syria union. |

| September 1971 | The Permanent Constitution of Egypt promulgated. |

| 1980 | Amendments to 1971 Constitution passed making Sharia the principal source of legislative rules |

| 2005 | Amendments passed to article 76 allow multi-candidate presidential elections |

| 2007 | Amendment tightens eligibility rules for presidential elections. |

| 10 Feb 2011 | Popular revolts force President Mubarak to request that articles 76, 77, 88, 93 and 189 be amended and that article 179 be removed. |

| 11 Feb 2011 | Mubarak steps down as president of Egypt |

| 13-15 Feb 2011 | Military suspends Constitution and shortly thereafter sets up panel to review specific articles of Constitution for submission to referendum |

| 19 March 2011 | Constitutional referendum |

| 30 Mar 2011 | Constitutional Declaration issued, calls the for the formation of Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution |

| 26 Mar 2012 | Constituent Assembly is formed and its composition sparks outrage |

| 11 April 2012 | Administrative Court dissolves the assembly as unconstitutional |

| June 2012 | A new Assembly is formed |

| 29 November 2012 | Constituent Assembly approves a constitutional draft |

| 15 and 22 Dec 2012 | Constitutional draft passes a public referendum. |

| 25 Jan 2013 | Two years anniversary of the 2011 revolt erupts in mass protest. |

| 30 June 2013 | Millions take to the street to protest and demand Morsi removal from office. |

| 3 July 2013 | Military deposes Morsi and installs and interim government. |

| 8 July 2013 | Interim President Adli Mansour issues a Constitutional Declaration |

| 3 December 2013 | The Committee of 50 submitted the new draft constitution to the interim president |

| 14-15 January 2014 | The Constitutional referendum was held. The new Constitution was approved. |

Bibliography

Abdullah Al-Arian, Egypt: Dr. Frankenstein's Constitution, Aljazeera (10/07/2013): http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/07/201371011199459549.html.

Anthony F. Lang, JR. From Revolution to Constitution: The Case of Egypt, 89 International Affairs 345 (2013). http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.proxy.wm.edu/doi/10.1111/1468-2346.12021/pdf.

Bassem Sabry, First Look at Egypt's Constitutional Declaration, Al-Monitor (08/07/2013). http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/07/egyptian-constitutional-declaration-post-morsi-transition.html.

BBC News. Egypt Country Profile. 2013. Web. 19 June 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13313370

Gerard Direct. An Examination Of Egypt’s Draft Constitution Part I: Religion And State – The Most Islamic Constitution In Egypt’s History. 2013. Web. 19 June 2013. http://gerarddirect.com/2012/12/04/analysis-egypts-draft-constitution-most-islamic-in-egypts-history/.

International IDEA. The New Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt. 2013. Web. 19 June 2013. http://www.constitutionnet.org/vl/item/new-constitution-arab-republic-egypt-approved-30-nov-2012.

James Feuille, Reforming Egypt’s Constitution: Hope for Egyptian Democracy?, 47 Texas International Law Journal 238 (2013). http://www.tilj.org/content/journal/47/num1/Feuille237.pdf.

Kelly Buchanan, Egypt’s New Constitution: General Overview of Drafting History and Content, Library of Congress (15/01/2013). http://blogs.loc.gov/law/2013/01/egypts-new-constitution-general-overview/.

Sarah El Masry, Egypt’s Constitutional Experience, Daily News (30/10/2012). http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2012/10/30/egypts-constitutional-experience-2/.

United States. CIA World Factbook: Egypt, 2013. Web. 19 June 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/eg.html.

Zaid Al-Ali, The New Egyptian Constitution: An Initial Assessment of its Merits and Flaws, Open Democracy (26/12/2012). http://www.opendemocracy.net/zaid-al-ali/new-egyptian-constitution-initial-assessment-of-its-merits-and-flaws.

Zaid Al-Ali, Another Egyptian Constitutional Declaration, Foreign Policy (09/07/2013). http://mideast.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2013/07/09/another_egyptian_constitutional_declaration.

Zaid Al-Ali and Nathan J. Brown, Egypt’s Constitution Swings into Action, Foreign Policy (27/03/2013). http://mideast.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2013/03/27/egypt_s_constitution_swings_into_action

| Branch | Hierarchy | Appointment | Powers | Removal |

|---|

Share this article