Constitution building in 2018 through the lens of ConstitutionNet and 2019 prospects

Introduction

While constitutions are central to the conduct of politics, they are not themselves immune to the vagaries of politics. Despite the characterization of constitutions as enduring or permanent texts, they are subject to continuous political, and sometimes violent, contestation, often resulting in adjustments and even outright replacements of the constitutional framework. The year 2018 has witnessed its fair share of efforts aimed at reworking constitutions. The Constitution-Building Programme of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) has been reporting on and organizing information on these developments through ConstitutionNet, the sole platform dedicated to generating, organizing and disseminating knowledge and updates on constitution building processes worldwide. In particular, the Voices from the Field series has given local experts a unique medium to provide detailed accounts of the background, process, actors, contentious substantive issues, and the prospects in constitutional reform processes in their respective countries. In this end of year editorial, we look back at some of the core issues in terms of both process and substance in 2018.

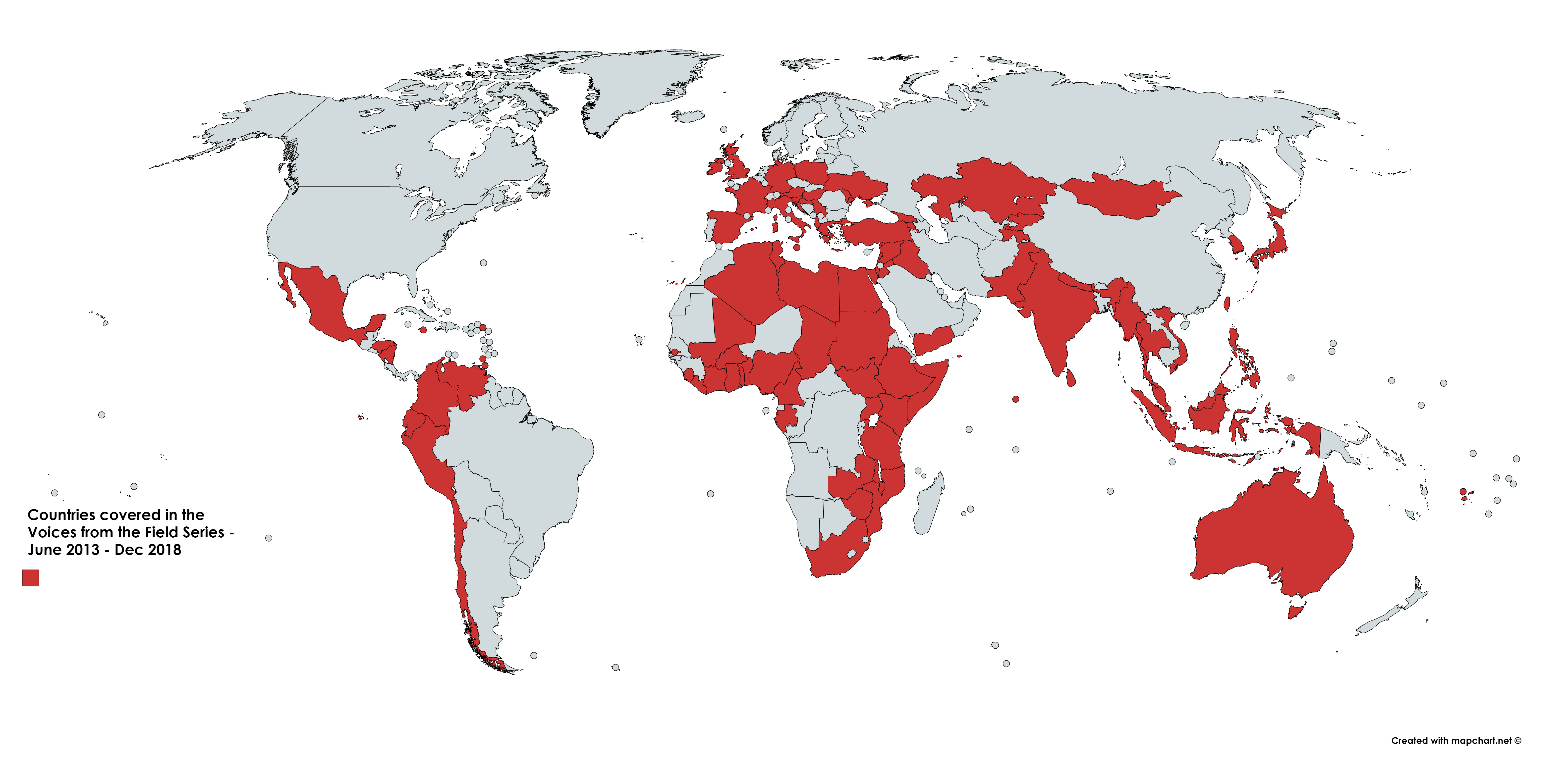

In 2018, ConstitutionNet published 40 Voices from the Field pieces covering 35 countries. These numbers do not include the large list of countries that were covered in the ConstitutionNet daily news updates. There are few countries in the world, large and small, that have not appeared on the radar, indicating the frequency of debates on constitutional governance frameworks.

New constitutions were finalized in 2018 in Burundi and Chad, some processes have stalled (e.g. Chile, South Korea), and many continue (Philippines, The Gambia, Tuvalu, Guyana).

In some of the countries, constitutional reforms are undertaken with a view to adopt new constitutions (e.g. The Gambia, Philippines), while in most cases the reform proposals take the form of amendments to existing constitutions. New constitutions were finalized in 2018 in Burundi and Chad, some processes have stalled (e.g. Chile, South Korea), and many continue (Philippines, The Gambia, Tuvalu, Guyana). The making of new constitutions usually involves higher levels of commitment to popular consultations, often through dedicated constitutional commissions or similar bodies, beyond the procedure anticipated in the formal rules of constitutional change, although in some cases the actual level and meaningfulness of participation may be questionable (e.g. Burundi and Cuba). Some level of popular participation is also increasingly common even in cases of amendment processes, regardless of the prescribed procedure. In terms of consequences, even reform proposals channeled through amendment processes could have significant symbolic (e.g. Israel declaring the state a Jewish National State) and institutional (e.g. Peru, proposing establishment of a bicameral legislature, and Chad, formally decentralizing power) implications to the constitutional dispensation. The characterization of the reform goal as the adoption of a ‘new’ constitution or an ‘amendment’ to an existing text does not necessarily determine the process and scope of change.

In Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen, the constitution making process has stalled, but ultimately remains central to the conflict-to-peace transition.

There are a number of countries not included in this year’s Voices from the Field contributions where the process of constitutional change has stalled, but ultimately remains central to the conflict-to-peace transition – for example Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen. As we approach the end of 2018, there are signs of progress being rekindled in several of these processes, and more progress could be reported on in early 2019.

On process: The promises and pitfalls of constitutional referendums

Constitutions increasingly provide for referendums to approve some or all proposed constitutional reforms. In some countries, members of the public may be empowered to directly propose constitutional amendments for a referendum through popular initiatives without the blessing of existing institutions. Constitutional referendums and popular initiatives provide useful mechanisms of enhancing popular participation and therefore the legitimacy of constitutional choices. Nevertheless, experiences from Burundi, Comoros and Ecuador in 2018 have reaffirmed the concern that powerful leaders and groups may resort to referendums to unilaterally push through reforms and bypass resistance from established institutions. Constitutional referendums may therefore weaken institutional mechanisms of democratic compromise and consensus building. Requiring referendums as complements rather than alternatives to institutional negotiation, through parallel approval requirements before referendum could be held, may partly address the challenge. Moreover, the experience with popular initiatives in Croatia show the need for mechanisms to ensure that the process does not unduly undermine the rights, interests and representation of insular minorities. Popular initiatives may also be hijacked by disgruntled political representatives, rather than serving as channels of popular empowerment, as the Kenyan experience may demonstrate.

Constitutional referendums may weaken institutional mechanisms of democratic compromise and consensus building.

The experience with Ireland’s Citizen Assembly, composed of randomly selected group of citizens tasked with making a proposal on the constitutional status of the contentious issue of abortion, may serve as one possible mechanism to address the information and deliberation gap that often characterizes constitutional referendums. Indeed, the Irish Citizen Assembly procedure was adopted as a precursor to inform the constitutionally mandated referendum on all constitutional reforms. Such assemblies may also attenuate the radical demands of vocal interest groups. Nevertheless, understanding of and experience with these processes remains limited for now.

On substance: Enduring challenges of centralization of power and political inclusivity

A quick perusal of the reform focus of the Voices from the Field pieces reveals the breadth of issues that were discussed as part of constitutional reforms worldwide. The pieces covered issues ranging from the rights of women and sexual minorities to citizenship to youth representation to expropriation of land without compensation to foreign relations. Themes related to the division of power, systems of government and electoral systems, as well as checks and balances dominated the reform debates. These debates reflect the enduring challenge of checking the centralization of power in the national executive and enhancing the representativeness and inclusivity of political institutions.

The thematic focus of reforms reflects the enduring challenge of checking the centralization of power in the national executive.

Constitutional reforms in a number of countries deal with the issue of decentralization/federalism. Some previously centralized countries, such as Mozambique, Chad, South Korea and Trinidad and Tobago, have sought to decentralize power to sub-national levels of government. Some relatively decentralized states, such as the Philippines, are considering a full-fledged move to a federal system of government. Some federations are seeking to streamline the division of powers, such as Austria, while others are working towards establishing formal mechanisms of intergovernmental coordination that can survive the breakdown of vanguard political parties and other informal coordination structures, as is the case in Ethiopia.

In addition to efforts to check the centralization of power through vertical decentralization, a number of countries are considering the possibility of adjusting the system of government in a manner that divides executive power or abolishes the executive presidency (Maldives, South Korea, Burkina Faso), while at the time enhancing checks and balances through legislative and judicial empowerment and other fourth branch institutions (Serbia, Malaysia, The Gambia). Political developments in Tunisia and Sri Lanka have also brought to the fore the practical complexities of adopting semi-presidential systems in contexts of weak political party systems. In Sri Lanka, significant political support exists for a potential move towards abolishing the executive presidency.

The appropriate electoral and government system also continue to occupy the imagination of constitutional reformers.

Another enduring constitutional issue relates to the electoral system for the legislature but also for the executive. In line with recent trends, some countries are considering the strengthening of proportional electoral systems (e.g. Armenia and South Korea). Nevertheless, the adoption of proportional representation may also incentivize party proliferation and legislative fragmentation. To address this challenge, Tunisia is considering the adoption of a minimum threshold for political parties to join parliament. While there appears to be a level of consensus on the importance of the threshold, there is concern that a high threshold could exclude smaller parties and undermine political inclusivity. As always, the choice over the electoral system is only a first order decision which requires choices on a series of related issues. As with all constitutional design decisions, it is important that actors pushing for reform of the electoral system understand and consider the entire gamut of choices and the factors to consider.

Concluding remarks

In the 2017 end of year editorial, we note that change is a permanent feature of constitutional systems worldwide, rather than merely occurring in waves. The scope and number of reforms that occurred in 2018 affirms this observation. Constitutional reforms will continue to feature in 2019. Some of the reform processes that started in 2018, such as in Cuba, The Gambia, Tuvalu and Venezuela may be concluded in 2019. New constitution reform processes are also likely to start, or restart, in Guyana, Uganda and Malta. As constitutional issues are central to the conflict in Libya, Syria and Yemen, an improvement in the security situation may strengthen the reform impetus. Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka and Ukraine may accelerate their constitutional reform processes. Beyond these prominent largescale constitution making initiatives to adjust constitutional frameworks through amendments are likely to occur throughout the world. ConstitutionNet will return in 2019 with a new look to generate original analysis of continuing and new reform efforts and to collate and organize news updates on constitutional reforms.

We hope you enjoyed our content in 2018. We wish you happy holidays and see you in 2019.

Adem K Abebe is the editor of ConstitutionNet.