Mapping Wales’s Constitutional Future: Insights from the Final Report of the Independent Commission

The Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales has unveiled its final report. Its inclusive approach has resulted in unanimous recommendations for immediate measures to safeguard devolution and enhance democracy in Wales. Looking to the longer term, the Commission also evaluated three constitutional options: enhanced devolution, Wales within a federal United Kingdom, and independence. But the fate of Wales's constitutional future ultimately hinges on how political parties within and beyond Wales respond to the Commission's findings – writes Dr. Anwen Elias

On 18 January 2024, the Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales published its final report. Launched by the Welsh Labour government in 2021, the Commission had two broad objectives: to consider and develop options for fundamental reform of the constitutional structures of the United Kingdom (UK), in which Wales remains an integral part; and to consider and develop all progressive options to strengthen Welsh democracy and deliver improvements for the people of Wales.

The Commission, of which the author was a member, was set up against a backdrop of long-running debates about the constitutional future of the United Kingdom. Recent events, such as the UK’s exit from the European Union and the Covid-19 pandemic have, in different ways, prompted clashes between UK and devolved governments (in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) over policy choices and how these are decided. These clashes reflect, but also drive, very different and competing political views on the UK’s constitutional future in different parts of the country. The result is a very polarised debate where positions in favour of strengthening or breaking-up the union dominate.

In this context, the establishment of the Commission signalled Welsh Labour’s desire to have a different kind of constitutional debate. This is reflected in the way that the Commission was set up and went about its work, and in its recommendations on how Wales – and the UK – could be governed in the future. Wales’s constitutional future will ultimately depend on the extent to which UK political parties engage seriously and constructively with the Commission’s findings, and commit to continuing the conversation in the way that has been modelled in Wales.

Organising a “national conversation” about Wales’s constitutional future

This is not the first commission in Wales to consider constitutional matters. Several previous commissions have considered issues such as the powers and the size of Wales’s parliament (formerly called the National Assembly for Wales until 2020) and electoral reform. These commissions were predominantly led by, and mostly engaged with, experts from politics, academia and civil society, with limited opportunities for the broader public to contribute. In the larger UK context, this is also not the first “national conversation” with a constitutional focus: the Scottish National Party instigated such a debate in 2007 as part of its campaign for Scottish independence (p. 20).

From the outset, therefore, the Commission sought to signal an inclusive approach that bridges party-political divides.

This Commission has been different to these previous examples in three ways. Firstly, it includes amongst its 11 members representatives from the four political parties currently represented in the Welsh Parliament (Welsh Labour, the Welsh Conservatives, Plaid Cymru and the Liberal Democrats). These members worked alongside non-political experts from academia, the media, civil service and civil society. From the outset, therefore, the Commission sought to signal an inclusive approach that bridges party-political divides. It is significant that the Commission’s findings – discussed further below – were unanimous. This was by no means guaranteed given the political parties’ ideological differences on constitutional issues: the Welsh Conservatives support the status quo, Welsh Labour and the Welsh Liberal Democrats advocate for a federal UK, and Plaid Cymru wants independence for Wales.

Secondly, the Commission received a very broad remit to explore and evaluate a range of constitutional options. These included different options for governing Wales, both as a distinct nation within the existing UK but also as a future independent state outside the UK. Based on evidence gathered during its first year of work, the Commission narrowed these options down to three for more detailed scrutiny: enhanced devolution (protecting and strengthening of the current devolution settlement), Wales within a federal UK, and an independent Wales.

Thirdly, the Commission’s “national conversation” adopted a variety of methods to engage as many different voices from across Wales as possible. Some of this engagement was typical for a commission of this kind: written and oral evidence sessions involving political parties, civil servants and civil society, and an online portal where citizens could directly submit their responses to key questions of interest to the Commission.

Other methods were more distinctive and ambitious. For example, deliberative citizens’ panels were held in eight locations across Wales. A Community Engagement Fund was also established to engage groups that do not typically participate in public consultations; these included children and young people who have been in care, people with learning disabilities, and youth and adults facing social exclusion and injustice (Final Report, p. 140). The views of these groups were gathered in a range of ways: group discussions and surveys, drawing, writing songs and taking photos. Furthermore, a programme of pop-up engagement events was organized in shopping and community centres, cultural festivals and family events. This qualitative data was complemented by two quantitative surveys in Wales and across the entire UK, providing more representative data on constitutional preferences (Final Report, p. 19).

The process of engaging citizens with the Commission’s work was challenging. People often did not consider constitutional issues to be important, and could not see how they mattered for their daily lives. Many also did not feel that they understood enough about how Wales is currently governed to have a view about how things could be done differently in the future. In response, the Commission had to work hard to try to speak to citizens in a way that was meaningful to them: this required avoiding technical and legalistic jargon, and linking constitutional issues to policies and services (such as health, education and transport) that people cared about. It also necessitated the mix of engagement approaches described above. The Commission adapted its engagement strategy through trying various approaches and feedback from citizens and experts, learning that different methods work better for reaching different people in different kinds of places. This took time, resources, and a willingness to innovate.

Citizens had views on how Wales is governed now and in the future, although they did not always articulate these using the terms used by politicians, experts and academics.

Such an approach gave the Commission invaluable insights into how and what people think about Wales’s constitutional future. Those the Commission heard from were interested in constitutional issues, and wanted to have a chance to discuss them. Citizens also had views on how Wales is governed now and in the future, although they did not always articulate these using the terms used by politicians, experts and academics. These views fed into all aspects of the Commission’s discussions: data from different sources were analysed and key themes and findings identified, and were considered alongside other information received in the form of written and oral evidence. This “national conversation” informed the Commission’s findings on the different options for Wales’s constitutional future, and its recommendations for protecting devolution and strengthening democracy in Wales in the shorter term.

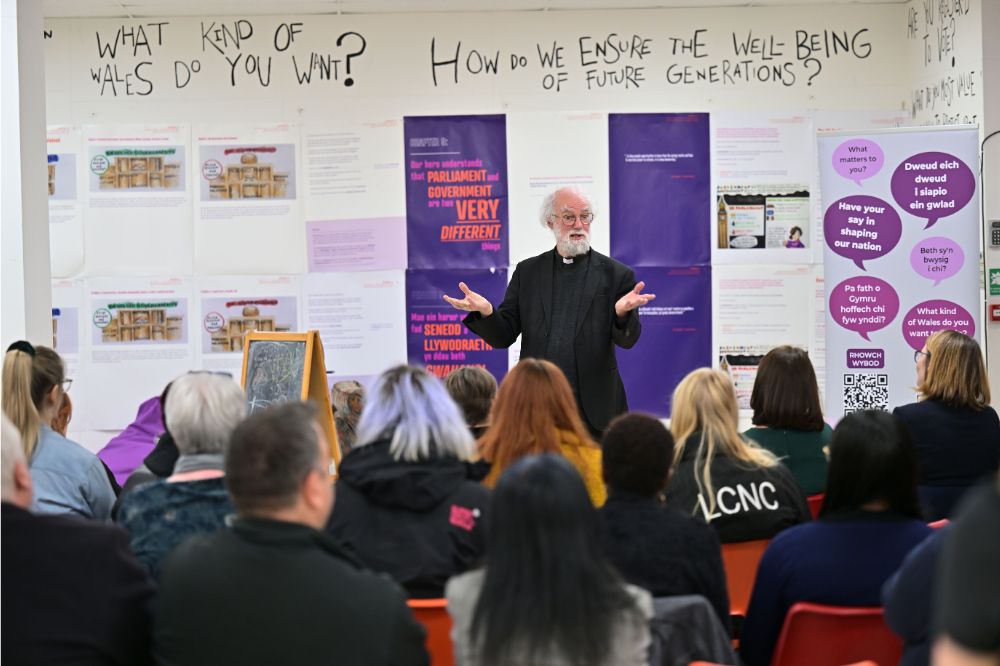

Overview of participation in the "national conversation" on the constitutional future of Wales (photo credit: Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales)

Options for the constitutional future of Wales

A key finding of the Commission’s work is that all three constitutional options considered – enhanced devolution, Wales within a federal UK, and independence – are viable. Significantly, the Commission did not endorse one option over another. Reaching such an agreement would have been impossible given the Commission’s composition. But it is also argued that such a choice ultimately rests with the people of Wales, based on their own values and perspectives.

Rather than advocating for a particular option, the Commission provides an evidence-based analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the different options, and identifies the opportunities and challenges inherent in each. It does this by applying a novel analytical framework, with each constitutional option being evaluated against three sets of criteria:

1. Principles of good governance: this includes accountability, agency, subsidiarity, and equality and inclusion;

2. Practicalities of implementing the options: this encompasses external dependencies, capacity and cost, stability, and co-ordinated government decision-making; and

3. Policies: this includes public finances, appropriate economic policies, and economic stability.

The resulting analysis sets out in detail how each of the constitutional options measures up against these criteria, and highlights the trade-offs between different criteria (Final Report, pp. 96–117). The Commission concludes that choosing between the different options depends on ‘the relative weighting given to the criteria in the analysis framework [and] the level of risk and uncertainty people are prepared to accept’ (Final Report, p. 112).

Recommendations for protecting devolution and strengthening democracy

Alongside this analysis of the long-term options for Wales’s constitutional future, the Commission also recommended changes aimed at protecting the devolution settlement in Wales in the short term. Some of these recommendations relate to the working relationship between the UK and devolved governments. For example, the Commission proposes strengthening the mechanisms of inter-governmental relations to improve co-operation between the central and devolved governments. Additionally, the Commission recommends new legislation in the UK parliament to ensure that the UK government cannot make policies in devolved areas of competence without the consent of the devolved institutions. The Commission also recommends the removal of current constraints on Welsh Government budget management to provide greater flexibility and improve cost effectiveness (Final Report, p. 7).

Other recommendations relate to the division of competences between Wales and the UK. The Commission considered six policy areas that are currently (wholly or partly) the responsibility of the UK parliament: broadcasting and public service media, energy, transport, justice and policing, and welfare. The case is made to devolve justice and policing (which are already devolved to Scotland and Northern Ireland) as well as rail infrastructure to Wales to address chronic problems with service delivery (Final Report, p. 71). In other areas – broadcasting and energy – there is a call for the voice of Wales at the UK level to be strengthened through improvements in shared governance. For example, clearer inter-governmental mechanisms in relation to decisions about broadcasting policy, funding and regulation, and energy regulation, generation and distribution.

A final set of recommendations aims to strengthen democracy in Wales by tackling citizens’ cynicism and disengagement with democratic politics.

A final set of recommendations aims to strengthen democracy in Wales by tackling citizens’ cynicism and disengagement with democratic politics. In this regard, planned changes to the size and electoral system of the Welsh Parliament – due to be introduced ahead of the next elections in 2026 – should be reviewed to evaluate their impact on voter choice and democratic accountability. Additionally, new capacities should be created to drive forward democratic innovations – such as citizens’ assemblies, participatory budgeting or collaborative governance approaches – as a means of involving citizens in decision-making between elections. The Commission also recommended that these innovative mechanisms of democratic participation should be used as part of a process to create a statement of constitutional and governance principles ‘as a way of consolidating constitutional principles in the devolution legislation and involving citizens in the way their country is governed’ (Final Report, p. 121).

What next for Wales’s constitutional future?

The Commission has started a conversation on Wales’s constitutional future: the next step in this journey depends on how political parties respond to, and take forward, the Commission’s findings and recommendations.

There are some things – such as the recommendations on strengthening democracy – that the Welsh Labour government can act on by itself, and immediately. But other constitutional reforms, both in the short and long term, can only happen with the support of, and action by, the UK government.

Wales’s constitutional future is ultimately not in its own hands . . .

As such, Wales’s constitutional future is ultimately not in its own hands. The Commission’s work has tried to put Wales on the front foot in relation to the big constitutional challenges facing the UK, and to start – and lead – a conversation about these challenges that is inclusive, respectful, and evidence-based.

In this respect, there are valuable lessons that others – in the UK and beyond – can learn from the Commission’s experience: the value of cross-party collaboration in the rigorous and objective gathering and analysis of evidence, and how to meaningfully engage citizens in a discussion of constitutional questions that directly impact their lives.

But it is only if others embrace the same approach to constitutional debate that change can happen. Failing to do so risks allowing the frustrations of citizens and politicians to fester and grow. This, in turn, will drive further polarisation and leave the big constitutional questions in Wales and the UK unresolved.

Dr. Anwen Elias is Reader in Politics at the Department of International Politics, Aberystwyth University. Dr. Elias is also a member of the Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Anwen Elias, ‘Mapping Wales’s Constitutional Future: Insights from the Final Report of the Independent Commission’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 30 January 2024, https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/mapping-waless-constitutional-future-insights-final-report

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in Wales and the United Kingdom.