Venezuela: Is a democratic transition possible?

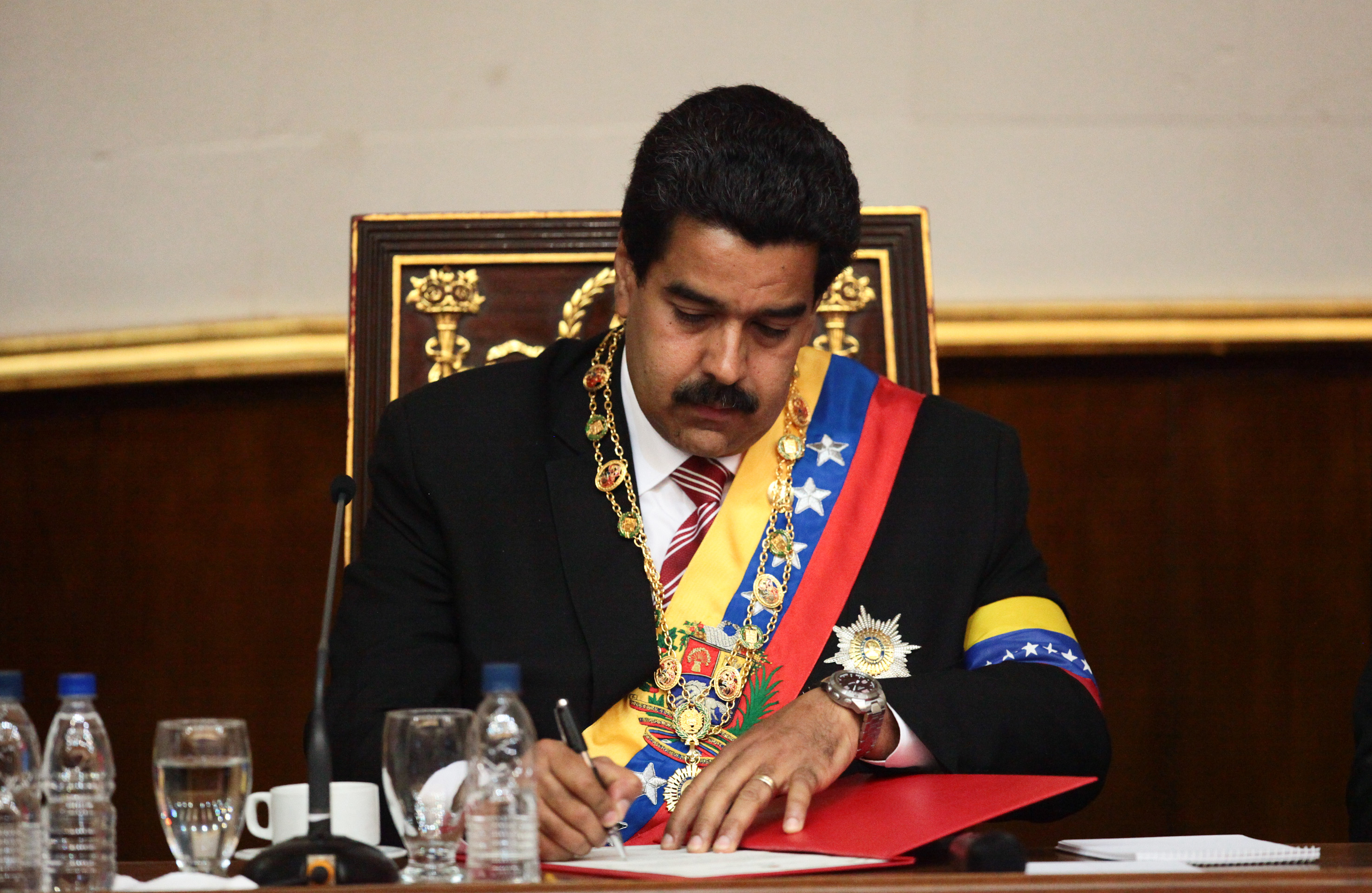

On 3 January 2026, U.S. special forces captured and extracted Nicolás Maduro, abruptly ending the rule of a leader who had governed Venezuela since 2013 through authoritarian means and fraudulent elections. The operation has reopened a long-dormant question: whether Venezuela can finally embark on a genuine democratic transition after decades of institutional decay. This article examines how Venezuelan democracy collapsed, why elections alone are insufficient to reverse authoritarianism, and what political, legal, and international conditions would be required to transform Maduro’s removal into a meaningful transition grounded in constitutional order and human rights.

In the early hours of 3 January 2026, U.S. special forces captured and extracted Nicolás Maduro, who has been serving as Venezuela's president since 2013 without free and fair elections and under an authoritarian regime. One of the key questions this action raises is whether a democratic transition is possible in Venezuela.

So far, while it is unclear whether Maduro's removal from power has put the country on a path towards a constitutional democracy, it represents a unique opportunity to do so after decades of authoritarian rule. To understand the conditions necessary to advance in that direction, we first need to summarize how democracy died in Venezuela.

The collapse of Venezuela’s democracy

Venezuela might serve as a prime example of how democracies collapse in the 21st century. It was not a military coup that caused it, but the election of a charismatic and authoritarian leader, Hugo Chávez, in 1998. Chávez, who attempted a coup d’état in 1992, committed to address the social grievances stemming from Venezuela's political decay and vowed to eliminate its political system. He delivered his promises, although the “old system” was not replaced by better governance but by an authoritarian regime bolstered by populist rhetoric and one of the highest oil windfalls in the country's history. Gradually, the Venezuelan democracy degenerated into a competitive authoritarianism.

Chávez's death, announced in 2013, deepened the crisis. His vice president, Nicolás Maduro, was chosen as president in a manipulated election, which the Inter-American Court of Human Rights considered a human rights violation. Without charisma and petrodollars, Maduro could only remain in power through systematic human rights abuses, especially in response to the 2017 widespread protests triggered by the unconstitutional move that stripped the opposition-controlled National Assembly of its legislative power.

By 2018, Venezuela became a non-competitive authoritarian regime, facing a complex humanitarian emergency triggered by the predatory policies that pushed the country to a state of fragility close to collapse, and where weak political institutions were co-opted by organized crime organizations, giving rise to a so-called "mafia state".

The opposition, supported by the Norwegian Government, sought to negotiate political terms to move towards an electoral solution in the 2024 presidential election. According to the vote tallies, the opposition candidate, Edmundo González, won by a landslide. However, Maduro refused to accept his defeat and instead used Venezuela’s politically influenced Constitutional Chamber to declare himself as president-elect, while repressing the large protests.

The process of a democratic transition

As Linz suggests, the process of transitioning to democracy varies based on the authoritarian regime being replaced. In that sense, I have concluded that Venezuela requires a complex transition encompassing three dimensions: political, economic, and statecraft.

The political and economic transitions will require rebuilding state capacity, including restoring Venezuela's legitimate state monopoly on the use of force and its territorial control.

The political aspect involves replacing the authoritarian regime with a constitutional democracy governed by the rule of law. To achieve that goal, it is also necessary, from an economic standpoint, to restore the market mechanisms, enabling civil society to satisfy its own needs so that it can organize itself effectively. The political and economic transitions will require rebuilding state capacity, including restoring Venezuela's legitimate state monopoly on the use of force and its territorial control. Without a capable state, it is not possible to reconstruct the rule of law and the economy.

Under this broader perspective, elections are clearly insufficient to advance a democratic transition. More importantly, advancing the complex transition will also require international support, especially given the difficulties in rebuilding state capacity. Particularly, international cooperation is essential to deter the systematic violations of human rights, pursuant to the responsibility to protect, a political commitment that establishes the collective duty of states to take collective action to protect the Venezuelan population from crimes against humanity currently under investigation by the International Criminal Court.

When considering this angle, the actions adopted by the U.S. could be framed as a case of an "externally directed” transition, according to Linz. There are, of course, many doubts about the legality of such actions under international law, particularly under a traditional approach that considers sovereignty an insurmountable barrier, even in the face of gross human rights violations.

But regardless of that discussion, the removal of Maduro from power could unlock the complex transition in Venezuela with the U.S. support and, more broadly, the international community. To that end, it will be essential to establish a transitional government in accordance with the Venezuelan Constitution.

What can we expect for Venezuela?

Although Maduro was removed from power, his authoritarian regime persists. His vice president, Delcy Rodríguez, assumed the presidency without complying with the constitutional framework for vacancies, instead relying on the Constitutional Chamber which, in a display of constitutional authoritarian populism, allowed Rodríguez to do so without holding elections.

(...) Rodríguez implemented an emergency decree, supposedly signed by Maduro, which paved the way for the government to further crack down on civil society and the opposition.

More importantly, because Maduro was not properly elected in 2024, Rodríguez's tenure can be deemed illegitimate as well. Not only the U.S., but also the United Kingdom, have clarified that she cannot be recognized as the legitimate and acting president of Venezuela. In addition, as a reaction to what was deemed an aggression by the U.S., Rodríguez implemented an emergency decree, supposedly signed by Maduro, which paved the way for the government to further crack down on civil society and the opposition.

The Trump administration, which considers Rodríguez as an interim and illegitimate authority, has pressured for advances in political liberalization, including the release of over 800 political prisoners as part of its initial policies towards Venezuela. These policies also include rebuilding Venezuela’s oil industry and gradually promoting the country's recovery. So far, however, according to the NGO Foro Penal, only a small number of political prisoners have been released, indicating a lack of genuine commitment to a transition by the interim authorities.

To transform the current political situation into an opportunity for democratic transition, instead of a continuation of Maduro’s authoritarian regime under a new leadership, it will be necessary to implement four policies: restoring popular sovereignty, placing human rights at the center of reforms, gradually restoring the rule of law, and addressing the most imminent risk derived from the pervasive state fragility. Finally, those four policies will require establishing a transitional government in accordance with the Constitution.

Restoring popular sovereignty

The first policy concerns the illegitimacy of Delcy Rodríguez. As Maduro's former vice president, her authority is rooted not in democratic elections but in an authoritarian grip. As an immediate solution, the interim government should evolve into a transitional government. Members of such a transitional government should be appointed by the current authorities, as they hold political power, but the process should be open and transparent and include public consultations with civil society and the opposition, including the political forces aligned with Edmundo González. The international community, drawing on the experience of the negotiation process facilitated by the Norwegian Government, could support this initiative.

From a legal standpoint, Articles 333 and 350 of the Venezuelan Constitution establish the duty of citizens to work toward the restoration of constitutional order when the Constitution is systematically violated, and recognize the right of the people to repudiate authorities or regimes that undermine democratic values and human rights. Consequently, those articles can provide the foundations for a state of constitutional emergency that could enable the establishment of a transitional government to take the decisions needed to gradually restore constitutional democracy.

Placing human rights at the center

As a second policy, such a transitional government should re-establish the centrality of human rights, not only through the release of political prisoners, but also the halting of systematic human rights violations, including arbitrary detentions, torture, and extrajudicial killings. Without fear of repression, the Venezuelan people can mobilize in support of the transition towards democracy. The importance of human rights also involves assessing how Venezuela may benefit from a transitional justice system that encourages current authorities to support the democratization process without allowing impunity. This system should be grounded in the centrality of victims.

Restoring the rule of law

The third policy focuses on gradually reinstating the rule of law by restoring the separation of powers and appointing independent officials in the different branches of government. Prompt action should be taken to nominate independent justices, especially for the Supreme Tribunal and its Constitutional Chamber, even before legislative reforms are enacted, to guarantee an independent and impartial judiciary. These reforms are vital to prevent criminal courts—currently under political influence—from perpetuating serious human rights violations.

Addressing pervasive state fragility

International cooperation should support the rebuilding of the state's capacity to resort to legitimate use of force, particularly to re-establish effective territorial control in areas undermined by irregular armed groups, including those engaged in illegal mining activities in the Orinoco Mining Arc. Because the Venezuelan Army does not have the technical capabilities to fulfil those tasks, international cooperation would help regain territorial control and replace the politically influenced police institutions that have committed gross human rights violations.

Establishing a transitional government

Only if those policies are implemented can the current political situation evolve into a transition towards democracy, rather than the continuation of an illegitimate regime engaged in systematic human rights violations.

The establishment of a transitional government can then pave the way for Venezuela’s democratic transition. From a strict constitutional law perspective, this should include the proclamation of Edmundo González as the elected president of the 2024 elections. Another alternative, which will require broad political consensus and, eventually, the resignation of González, is to call new presidential elections under a new independent electoral management body.

Either scenario, however, can only be achieved after institutional reforms that restructure the current interim and illegitimate government into a transitional government (...).

Either scenario, however, can only be achieved after institutional reforms that restructure the current interim and illegitimate government into a transitional government operating under the authority of Articles 333 and 350 of the Venezuelan Constitution. During the transition to democracy, these articles will be key in enabling decision-making that, although not explicitly established in the Constitution, is necessary to restore constitutional order. However, such decisions should adhere to the constitutional values outlined in Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution, including respect for human dignity. To achieve this, a new, independent Constitutional Chamber should assist in interpreting these articles in accordance with human rights.

Conclusion

Once a freely elected government is in place and the transition concludes, it may be worthwhile to consider adopting a new Constitution to strengthen the restored democracy by reducing the powers of the Presidency and promoting a decentralized form of governance in Venezuela. However, due to the current political climate, the first goal should be to work towards restoring the effectiveness of the 1999 Constitution.

While the removal of Nicolás Maduro does not constitute a step towards democratic transition, it does present a unique chance to craft a transitional government rooted in human rights and the principles underpinned in the Constitution. If this opportunity is not seized, Maduro's authoritarian and predatory regime will persist under the new leadership, causing further deterioration of the Venezuelan state and continued, severe human rights violations.

About the Author

José Ignacio Hernández is a constitutional law professor at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Venezuela. He is a visiting scholar at Boston College Law School, a fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, and an adjunct professor at the American University Washington College of Law.

Suggested Citation

José Ignacio Hernández, ‘Venezuela: Is a democratic transition possible?’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 22 January 2026, https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/venezuela-is-a-democratic-transition-possible

Further Reading

Updates on constitutional developments in Venezuela.

Contribute to Voices from the Field

If you are interested in contributing a Voices from the Field piece on constitutional change in your country, please contact us at constitutionnet@idea.int.