Delivering Equality: Long Delayed Constitutional Change in Ireland

Scheduled for International Women's Day in 2024, an upcoming referendum on gender equality seeks to address outdated gender stereotypes in Ireland's Constitution. This referendum, rooted in the recommendations of a Citizens’ Assembly and enjoying broad political support, presents a significant opportunity for progress. However, the success of this referendum hinges on whether its text will effectively revise sexist language, acknowledge the value of care in society, and create a more inclusive definition of family - writes Ivana Bacik

Introduction

On 21 November 2023, the Irish government announced the planned date of a long-awaited, and previously delayed, gender equality referendum. Now scheduled to take place on 8 March 2024 – International Women’s Day – the referendum follows years of extensive debate about the necessity of amending the Irish Constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, to ensure that it offers stronger protection for gender equality and families not based on marriage. Indeed, the text of the Constitution, adopted in 1937, is overdue for amendment in many respects. It is widely agreed that the language used in the Fundamental Rights provisions in the Constitution that relate to women are particularly outdated and that, as required by Articles 46-47 of the Constitution, a referendum will be needed to amend, remove or replace these provisions.

The Constitutional ‘Family’

Article 41 of the Constitution deals with ‘The Family’. Of all the provisions, this is seen as most problematic and overdue for amendment, as noted previously by this author and many others. Article 41.2.1 states that ‘by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved’. Article 41.2.2 further refers to ‘mothers’ as having ‘duties in the home.’ Fathers are not mentioned anywhere in the text, and only those families which are based on marriage are offered constitutional protection; Article 41.3.1 provides that ‘The State pledges itself to guard with special care the institution of Marriage, on which the Family is founded, and to protect it against attack.’

Women’s groups protested at that time outside the seat of the national parliament at the way in which the text confined their role to the private sphere, to lives within the home . . .

Even in 1937 when the Constitution was adopted, this language was criticised for its blatant sexism. Women’s groups protested at that time outside the seat of the national parliament (Oireachtas) at the way in which the text confined their role to the private sphere, to lives within the home. This text, at least in part deriving from Catholic doctrinal teaching of the time, and adopted when a ‘marriage bar’ required women to resign from workplaces in the public and semi-state sectors upon marriage, offered a constitutional underpinning to such laws and policies. Indeed, that particular outrageous restriction on women’s freedom to work continued until 1973.

In the same year, Ireland joined what was then the European Economic Community (EEC), that evolved into European Union (EU) membership, which was to have a very significant impact for women’s rights, leading to the adoption of many important new laws in Ireland, such as those providing for maternity protections and gender equality in pay.

Over the decades since then, women have increasingly taken up prominent leadership roles in public life. Although Ireland’s Lower House (Dáil Éireann) remains far too male-dominated (76.9 per cent of members of the Lower House are men), women and mothers have been elected President, are running successful businesses, flying commercial planes, presiding over superior courts and competing at top levels in international sports arenas. Yet within Ireland’s fundamental legal text, women and mothers remain embedded exclusively within the domestic sphere, as if the marriage bar was still in place.

The Equality Guarantee

Despite the highly gendered nature of the text in Article 41, the Constitution does also contain a general ‘equality guarantee’ in Article 40.1, which provides that:

All citizens shall, as human persons, be held equal before the law. This shall not be held to mean that the State shall not in its enactments have due regard to differences of capacity, physical and moral, and of social function.

This text has been largely ineffective when used by litigants, and the ‘social function’ proviso has been interpreted as contributing to its highly restrictive application by the courts in practice. Further, the text does not refer specifically to sex or gender as a ground of discrimination, unlike the equality guarantee contained in Article 3 of the earlier constitutional text adopted by the Irish Free State in 1922, which referred to ‘Every person, without distinction of sex…’. There has been much academic speculation as to why similar language was not used in the text of Article 40.1, and many commentators have acknowledged the largely ineffective impact of the equality guarantee.

The Need for Change

The need for change to the constitutional text in Articles 40 and 41 has thus long been recognised; indeed, multiple reports and scholarly articles have called for removal or replacement. It has now become accepted that the current language relating to women and mothers in Article 41, in particular, is based on outdated gender stereotypes, and should have no place in a contemporary constitutional text. Nor does Article 41 recognise the various forms of care, both inside and outside the home, both paid and unpaid, carried out by both men and women, so vital to Irish society. Further, the definition of family in the Article has long been criticised for limiting protection to the marital family only – a highly restrictive definition which does real injustice to the wonderful diverse reality of family life. So it is now self-evident that there is an urgent need to delete the sexist language, recognise the value of care and create a more inclusive definition of family.

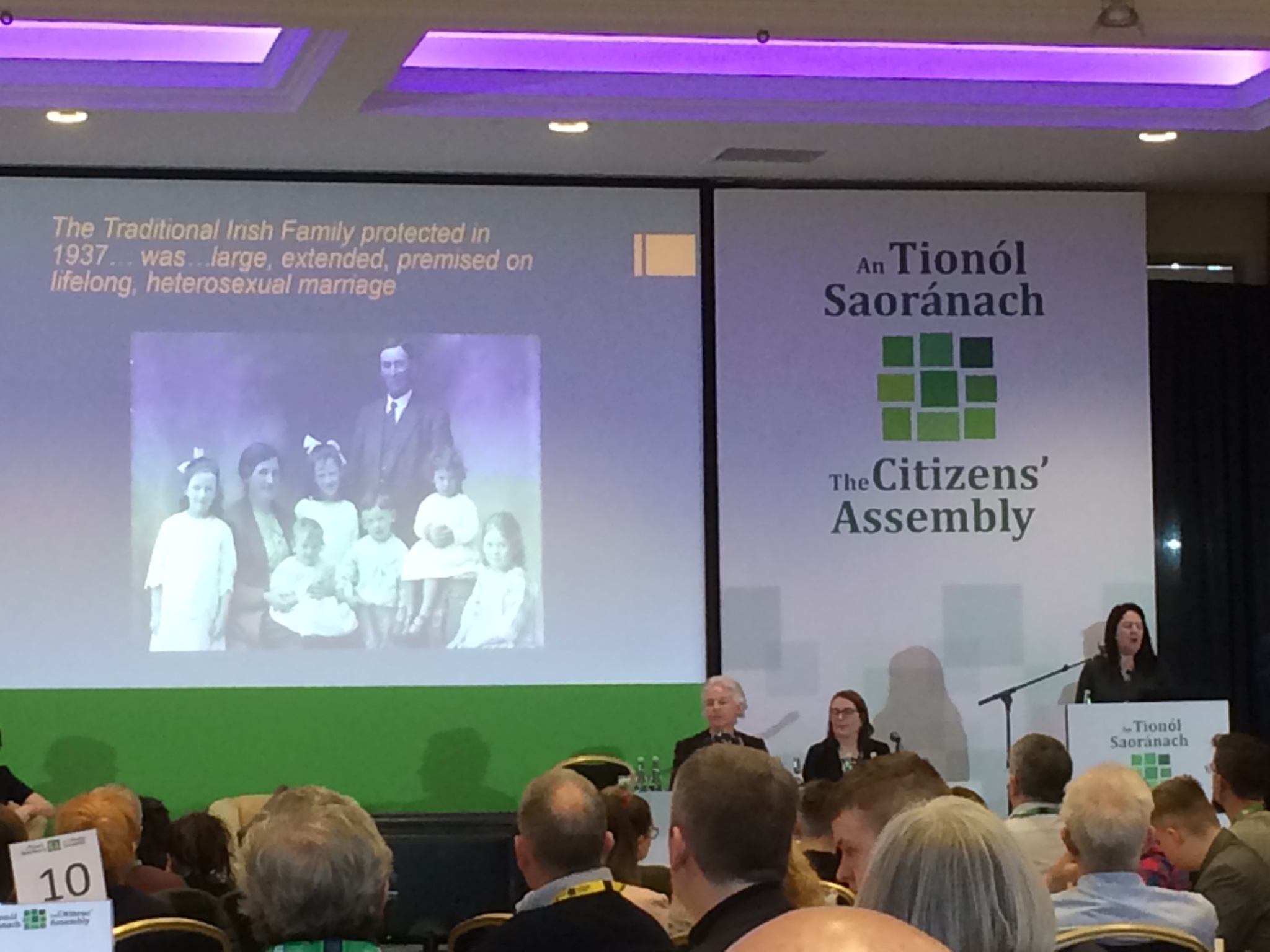

In 2020 the Government established a 100-member Citizens’ Assembly on Gender Equality, charged with tracking a pathway towards constitutional and legal change for a more equal Ireland.

Numerous reports and expert opinions have been commissioned by successive governments on how to make these changes. Most recently, in 2020 the Government established a 100-member Citizens’ Assembly on Gender Equality, charged with tracking a pathway towards constitutional and legal change for a more equal Ireland. The Assembly, comprised of 99 randomly selected citizens and a chairperson, met between January 2020 and April 2021. In 2021, the Assembly produced its final report, setting out a total of 45 recommendations for wide-ranging constitutional and legislative change. In the first three recommendations, the Assembly provided a clear framework for amending the text of both Article 40.1 and Article 41 (pp. 50-53).

The Assembly made three clear proposals for change to the Constitution, as follows:

- Article 40.1 of the Constitution should be amended to refer explicitly to gender equality and non-discrimination.

- Article 41 of the Constitution should be amended so that it would protect private and family life, with the protection afforded to the family not limited to the marital family.

- Article 41.2 of the Constitution should be deleted and replaced with language that is not gender specific and obliges the State to take reasonable measures to support care within the home and wider community (p. 12).

Implementing the Citizens’ Assembly Recommendations – the Referendum

Following the publication of the Citizens’ Assembly report, a cross-party joint parliamentary Committee on Gender Equality was established, of which the author was appointed Chairperson. The Committee’s mandate was to provide proposals to the Government and legislators on the most effective way to implement the Assembly’s recommendations. Over a short time period of nine months, the Committee held hearings with stakeholders and experts, examined the Assembly recommendations and devised a blueprint for their implementation. In its December 2022 report, entitled ‘Unfinished Democracy’, the Committee provided precise wording for replacement constitutional text to give effect to the three constitutional changes recommended by the Citizens' Assembly – wording which had unanimous cross-party support. The Committee called on the government to move swiftly to call the necessary referendum, recommending that the referendum should take place before the end of 2023.

The Committee provided precise wording for replacement constitutional text to give effect to the three constitutional changes recommended by the Citizens' Assembly – wording which had unanimous cross-party support . . .

Following publication of this report, the Taoiseach gave a public assurance in March 2023, on International Women’s Day, that the necessary referendum would take place in November 2023. The Taoiseach stated that an interdepartmental group was working on revised wording for the proposed constitutional amendment, to be published in May 2023. When no referendum wording was published by July 2023, further inquiries were made regarding the referendum timeline. Subsequently, in September 2023, the Taoiseach announced the postponement of the referendum once more, citing concerns about disinformation and the need to provide the Electoral Commission with sufficient time to conduct a public information campaign.

Analysis and Conclusions

While the latest news is that the referendum will take place in March 2024, the failure of the government to follow through on holding a gender equality referendum to date really matters. The failure to amend the equality guarantee matters to women denied workplace equality, and to carers whose immense contribution remains desperately undervalued. And the failure to amend the provision restricting recognition of ‘The Family’ really matters to families denied state recognition. For instance, cases like that of Johnny O’Meara, father-of-three, have been widely publicised; he was denied a widower’s pension upon the death of his long-term partner Michelle Batey, because they were not married. His case, currently before the Supreme Court, demonstrates the practical impact of a cruelly restrictive and anachronistic text that urgently requires amendment.

Undoubtedly, the wording of any referendum text must be legally robust and the national Electoral Commission must have enough time to ensure public debate is properly informed prior to the referendum. But while developing the appropriate wording for any constitutional change is always complex, as this author has previously argued, it is not rocket science.

There is no need for further delay; much work has already been done in preparation. A confident and competent government would not have engaged in the extraordinary foot-dragging and prevarication that has been seen on this in Ireland over recent months, and indeed over many years previously. While a date for the referendum has now been set, it is not yet clear whether the wording will follow the recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly and Oireachtas Committee, and it would be most unfortunate to see any further delays or unnecessary obstacles to making the long overdue constitutional change -– for a more equal Ireland.

Ivana Bacik TD is the Chairperson of the Oireachtas Special Committee on Gender Equality and a member of Dáil Éireann.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Ivana Bacik, ‘Delivering Equality: Long Delayed Constitutional Change in Ireland’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 30 November 2023, https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/delivering-equality-long-delayed-constitutional-change-ireland

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in Ireland.