Secularism and the Constitution of India: controversy under the Modi administration

Typically, technical disputes around Preambles to Constitutions are the preserve of tweed-jacketed constitutional scholars. Yet, the recent controversy over the meaning and content of the word “secular” in the Preamble of India’s post-independence constitution has been at the centre of public debate.

Context: the May 2014 Parliamentary elections and their aftermath

The May 2014 elections for India’s 16th Parliament are now universally regarded as a watershed event. These elections resulted in a historic win for the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) coalition, which secured 336 out of a total of 542 seats in the Lok Sabha (the Lower House of the Indian Parliament). The coalition’s main constituent, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) secured a simple majority on its own by winning 282 seats. The NDA’s victory gave it a mandate to overcome the perceived paralysis of the Indian National Congress (INC)-led coalition government of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), which had been in power since 2004.

The May 2014 election campaign was spearheaded by the BJP’s controversial Prime Ministerial candidate, Narendra Modi. Given the scale of the victory and the number of seats secured by the BJP alone, even sober political commentators spoke of the emergence of a ‘Modi wave’ and of his singular contribution to the spectacular political triumph. Alongside such reactions, some fear a return to the divisive policies that threatened the constitutionally protected rights and interests of religious minorities in India during the NDA governments of 1998 and 1999. In particular, critics recalled both the BJP’s general image as a right-wing Hindu party and Narendra Modi’s tenure as the Chief Minister of Gujarat during the 2002 riots that led to the killing of over a thousand Muslims and sparked universal outrage. Even these commentators, however, conceded that the reason for the UPA government’s defeat lay primarily in its waffling policies and the Modi campaign’s strong focus on issues of economic development.

Following the general elections, the Modi government won state elections in significant state legislative assemblies. At the same time, the return of the BJP to power has led to growing jingoistic comments nationwide, particularly by BJP MPs and party associates. There were also disturbing acts of political violence including the targeting of minority communities, Muslims and Christians in particular. Some commentators called on the Prime Minister to rein in such forces but his office maintained a studied silence - giving rise to fears that they were being implicitly endorsed or encouraged for the sake of potential votes in state elections.

The Preamble Imbroglio: A storm in a teacup?

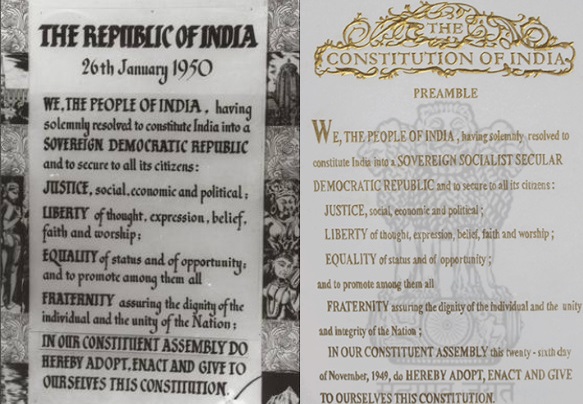

The controversy over the Preamble started in a deceptively simple fashion. On January 26, 2015, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting issued an advertisement in several dailies to mark the holding of Republic Day. The advertisement included a picture with the text of the original Preamble of India’s Constitution as adopted in January 1950. This text did not include the words “secular” and “socialist” as these terms were introduced into the Preamble through the 42nd Constitutional Amendment by the Indira Gandhi government in 1977. Although the original Preamble did not contain these specific words, several provisions in the Constitution, especially those relating to “Fundamental Rights” and “Directive Principles of State Policy” entrenched particular variations of secularism and socialism in keeping with the vision of the framers.

In a different era, the picture of the original Preamble and the somewhat understandable omission of the words in question may have passed without notice. However, given the above backdrop, some citizen groups highlighted the issue and questioned whether the omission was motivated by malicious considerations.

Among the first responses from the BJP government was a forceful reaction from the Union Telecom Minister, Ravi Shankar Prasad arguing that “[w]e do not need these words to be a secular country; even without them we are a secular country.” Pointing out that the two words were illegitimately imposed by Indira Gandhi’s government in 1976 during the period of internal emergency, Mr. Prasad asked the question: “What is wrong if there is a debate on these two words. Let us see what the nation wants.” More fuel to the already raging fire was added by a Member of Parliament of the Shiv Sena - a party allied with the BJP - when he stated:

"We welcome the exclusion of the (secular and socialist) words from the Republic Day advertisement. Though it might have been done inadvertently, it is like honouring the feelings of the people of India. If these words were deleted by mistake this time, they should be deleted from the Constitution permanently."

Prasad’s statement sparked off a furore and several other voices joined the public debate, including constitutional scholar, Upendra Baxi, who wrote an op-ed that helps clarify the legal issue at hand. Baxi first noted that:

“In 1973, the judgment on Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala articulated the doctrine of basic structure and the essential features of the Constitution, laying down that “secularism”, “socialism” as well as the Preamble to the Constitution (which may not be amended unless it was according to prescribed constitutional procedure) were integral to them. With effect from January 3, 1977, the Constitution (Forty-second Amendment) Act amended the Preamble and India was declared a sovereign, secular, socialist, democratic republic. Although the 42nd amendment was reversed in key aspects by the post-Emergency 44th amendment, which took effect from June 20, 1979, the amended Preamble was not changed. It has remained unchanged since 1977.”

Baxi went on to assert that

“[g]oing strictly by constitutional law, there is nothing called an original Preamble. True, when it was adopted, the Constitution did not include the terms “socialist” and “secular” as it now does. And it does so because the Supreme Court of India willed it before Parliament and the political executive did. Today, there is only one Preamble, which is enforced by the amendment that came into force in January 1977. No ministry at the Central or the state level is legally competent to say otherwise. The Constitution may not be amended by the executive. Only Parliament has the legal power to amend and even this would be valid if the justices of the Supreme Court were to hold that the amendment did not offend the basic structure or the essential features of the Constitution.”

Other legal experts concurred that Mr. Prasad’s call for a debate was “redundant” and “unnecessary.” At first sight, it appeared that the debate over the Preamble was a minor issue, one that would quickly fade away. However, more recent events seem to indicate that this controversy may well have served a useful purpose.

The Prime Minister’s intervention in the wake of the controversy

The controversy over the Preamble advertisement has embarrassed the BJP at a time when Prime Minister Modi had raised the stakes by inviting President Obama to attend the annual Republic Day parade as a guest of honour. Although much of the international and domestic media coverage focused on the bonhomie between the two leaders, even President Obama felt obliged to make a veiled reference to the BJP’s track record on minority rights by invoking the constitutional provision on freedom of religion in his last public speech in Delhi.

Shortly after the Obama visit, elections were held for the Delhi legislative assembly. Prime Minister Modi held rallies across Delhi and the BJP’s campaign in the state relied greatly on the ‘Modi effect’ which had proved to be remarkably successful in the 2014 general elections. Yet, on February 10, 2015, the expected BJP win did not occur and the party earned only 3 out of 70 seats in the Delhi Legislative Assembly. Analysis of the election results revealed that the debacle was in part due to members of minority groups in Delhi, including not just Muslims and Christians but also Sikhs, who had voted against the BJP in huge numbers. It now seems evident that the BJP’s weak commitment to the value of secularism had some role to play in the lost support.

The most encouraging sign that the BJP may have registered this message came in the form of a public speech by Prime Minister Modi on February 17, 2015. Speaking at a Catholic celebration, the Prime Minister made clear:

“My government will ensure that there is complete freedom of faith and that everyone has the undeniable right to retain or adopt the religion of his or her choice without coercion or undue influence. My government will not allow any religious group to incite hatred against others, overtly or covertly. Mine will be a government that gives equal respect to all religions.”

What is interesting about Prime Minister Modi’s statement is his explicit reliance on the Constitution of India as authority for his stance. For the moment at least, this should put to rest any doubts among his allies and Cabinet members about the legal and constitutional status of secularism in India. As one commentator has noted, the Delhi elections and the ‘Obama effect’ may well have led Prime Minister Modi to break his silence on this issue that is central to contemporary constitutional concerns in India. It may well be that the advertising campaign for the Republic Day celebrations to mark the 65th anniversary of the Constitution of India also had a part to play.

Whatever be the cause, if the result is that a primary constitutional value of Indian constitutional democracy is reaffirmed at this critical juncture, then that is certainly cause for celebration.

Arun K. Thiruvengadam is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, with a primary research and teaching focus on Indian constitutional law, South Asian law and politics and comparative constitutional theory and practice.