Reforming the Content, Rather than Context, of the Chadian Constitution: Old Wine in a New Bottle?

Constitutional reforms in Chad, promulgated in May 2018, formally enhance the decentralized system of governance, while strengthening the powers of the president in the central government. Despite calls for a referendum, the government opted to use parliament, whose mandate has been extended without fresh elections since June 2015, to approve the reforms. Crucially, mere changes in the content of the constitution, without a corresponding change in the context within which power is exercised, are unlikely to lead to constitutionalism - writes Sioudina Mandibaye Dominique.

Background

On 30 April 2018, the Chadian National Assembly approved with a two-thirds majority the revised Constitution. While two members of the ‘moderate’ opposition participated in and voted against the revised constitution, other opposition members boycotted the parliamentary proceedings. President Idriss Deby Itno promulgated the constitution on 4 May 2018, officially launching the Fourth Republic of Chad.

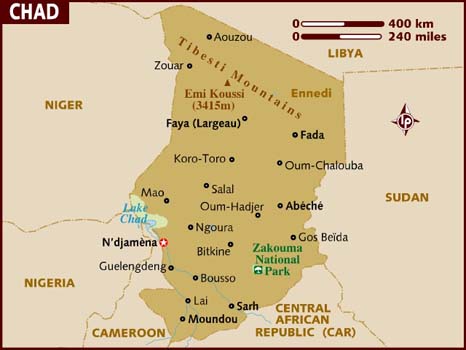

A former French colony, Chad has been under Deby’s leadership since 1990, who came to power after overthrowing the one-party dictatorship of Hissen Habre. His ruling party, the Patriotic Salvation Movement (MPS - Mouvement Patriotique du Salut), has also dominated the legislature since then, and currently controls, alongside its affiliates, more than two-thirds of the seats in the unicameral parliament. The current parliament was due to be dissolved in June 2015. Nevertheless, parliamentary elections were postponed and are expected to be held sometime in 2018. The Constitution was adopted in 1996 and was amended in 2005, notably removing presidential term limits, and in 2013. A predominantly Muslim country, Chad is also home to a sizable Christian minority, mainly concentrated in southern regions.

Parliamentary elections have been postponed since June 2015.

The proposed constitution emanated from the work of the Technical Committee for Constitutional Reforms (Technical Committee), which was established to give effect to the campaign promise of President Deby in the 2016 presidential elections, in which he won a fifth term, to reform the constitution. Following consultations in all regions of the country, the Technical Committee submitted its report to the government. The Committee proposed a number of reforms including decentralization of powers, rather than a federal system, despite demands for a federal system from the southern, predominantly Christian regions. The Committee also proposed the establishment of a bicameral parliament and the reinstatement of presidential term limits, with a corresponding increase of the duration of terms from five to seven years. The review process was largely dismissed by opposition groups and civil society organizations as an opportunistic strategy to allow Deby to enhance his grip on power.

Opposition groups and CSOs have dismissed the process as opportunistic, instead demanding a political dialogue.

The proposals of the Committee were then submitted to an ‘Inclusive National Forum’. The Forum submitted its report, which included 75 recommendations, in which it endorsed some of the proposals of the Committee and modified or rejected others. The government endorsed the report of the Forum and, following the review of the final proposals by a technical committee of legal experts, amendment proposals were submitted to the National Assembly. To speed up the implementation of the recommendations of the Forum, Deby appointed Mariam Mahamat Nour, who was the vice chairperson of the Forum, as the minister general secretary of the government in charge of the reforms.

The Inclusive National Forum

The Inclusive National Forum was held from 19 to 27 March 2018. It gathered 1 169 participants from different regions of the country and Chadians living abroad. The Forum took decisions by consensus. Nevertheless, it was boycotted by the main opposition coalition, which instead demanded an inclusive political dialogue. Such dialogue would have focused on reforming the socio-political context by opening up the political space, rather than merely focusing on shifts in the content of the constitution. Moreover, for most Chadians, constitutional reform and the gathering of the Forum have little impact on their daily lives and are not priorities in a time of recession, which the government has used to justify reductions in civil service salaries. Despite the objection of the opposition groups and civil society organizations, the government through its ruling party, MPS, succeeded in launching this Forum with its allies.

The discussions of the Forum focused on six main themes: the form of the state; the readjustment of the main institutions of the republic; the legislative process; the consolidation of peace, national identity, and good governance; judicial reform; and the promotion of the interests of women and the youth. In addition to discussing the need for appropriate institutional reforms, the Forum implored Chadians to change their behavior and mentality towards basic values of peace, national unity, good governance and respect of human rights, which should be the pillars of the new Fourth Republic. In particular, the issue of national unity has remained a critical challenge for successive Chadian governments because of the largely peaceful but fragile co-existence between the two dominant religious communities, Muslims and minority Christians.

The new provinces would enjoy more constitutional autonomy regarding the allocations of resources and competencies.

Following a technical assessment of the recommendations of the Forum by the government, the bill for the revised constitution of Chad was sent to the parliament for adoption.

Key reform proposals: Towards a decentralized state and presidential government

President Deby promised during his presidential campaign in February 2016 that, if reelected, he would establish federalism as a new form of state. Nevertheless, the Inclusive National Forum instead endorsed the recommendations of the Technical Committee for Constitutional Review for a decentralized unitary state. The Forum proposed the establishment of a unitary state with two levels of decentralized collectivities: provinces and departments. With this new territorial breakdown, the country will have 17 provinces with power and significant resources compared to the current 23 regions. Levels of government below the departments would be abolished. According to the recommendations of the Forum, the new provinces would enjoy more constitutional autonomy regarding the allocations of resources and competencies between the central government and the local collectivities. Crucially, some of the heads of the provinces would be popularly elected while others may continue to be appointed by the president.

The reforms abolish the position of prime minister, establish a fully presidential system, reinstate term limits, and increase terms from five to six years.

In closing the Forum, Deby noted that, despite his preferences for a ‘federation or regionalization’ based on his ‘project of society’, this was not unanimously adopted in the Forum. Nevertheless, he will ‘bow to the free and sovereign choices’ of the Forum. According to the Forum participants, and supporters of a unitary state structure in general, considering the long history of serious internal conflicts and fragile coexistence, a federal state structure in Chad could lead to the partition of the country.

Perhaps the most notable reform proposal relates to the move to a fully presidential system. The Technical Committee for Constitutional Reform had considered but ultimately declined to support the establishment of the position of the vice presidency. The Forum went further and recommended the scrapping of the post of the prime minister, which would end the nominal semi-presidential system of government. This new system would be similar to the one currently applied in Benin. The experience has shown that the fully presidential regime without a post of prime minister or vice president could have an adverse impact on the ability of the president to efficiently handle emergencies and effectively coordinate governmental actions in case of his absence. The first government of the Fourth Republic was formed on 8 May 2018. To fill the gap created by the resignation of the Prime Minister, the President has appointed Delwa Kassire Komakoye, Chairman of the National Inclusive Dialogue, as Minister of State.

Parliament rejected proposals of the Forum to impose term limits on MPs.

In line with the recommendations of the Technical Committee, the Forum recommended the reinstatement of presidential term limits. Henceforth, presidents may only serve two terms. Nevertheless, the term limits will only apply prospectively, thereby allowing Deby to run for a sixth (and possibly seventh) term in 2021 when he will be 70 years old. The Forum reduced the seven-year presidential term proposed by the Technical Committee to six years, which is still more than the current five-year term. Nevertheless, the proposed reforms raise the minimum age requirement to stand in presidential elections from 35 to 45, which would exclude a large group of people from standing for the presidency. This change contrasts with proposed changes in other countries, such as Nigeria, where the minimum age limit requirement has been reduced.

The Forum also proposed term limits for members of parliament and other elected mandates. But parliament rejected this proposal. Accordingly, all elected mandates provided for in the revised constitution, other than members of parliament, may only be renewed once. The duration of the term of members of parliament will increase from four to five years. The Forum further proposed that the number of members of parliament be reduced from 188 to 140, to be elected based on the newly established departments as constituencies. The Forum recommended the adoption of a 30% quota for the representation of women in relation to all elected and appointed positions. The quota proposition was made by the President himself but never implemented. Accordingly, the Forum decided to include it as part of the provisions for the new republic.

The Constitutional Council is abolished and reconstituted as a chamber of the Supreme Court.

In addition to the post of prime minister, the Forum recommended the abolition of the Office of the Ombudsman, an institution in charge of conflict resolution and mediation including those involving political and military conflicts as well as intercommunal conflicts, and the College of the Monitoring and the Surveillance of Oil Revenue. These two institutions were established by law, not in the constitution. The proposals of the Technical Committee for the establishment of a bicameral legislature was rejected by the Forum. Moreover, under the reforms, the General Accounting Court, the Constitutional Council and the High Court of Justice (an ad hoc tribunal in charge of high treason) are abolished and reconstituted as chambers of the Supreme Court. The abolition of these institutions would ostensibly help the government to save money at a time where the fall in oil and commodity prices has put pressure on government coffers.

In line with Deby’s campaign promises to combat corruption and improve good governance, and the recommendations of the Technical Committee, the Forum proposed the establishment of a special Economic and Financial Crimes Court. A military court will also be established.

Inter-religious disagreement on the question of ‘Diya’

During the discussions in the Forum, religious antagonism between the Muslim community and Christian community surfaced regarding Diya or ‘blood money’. Under this practice, predominantly followed by the Muslim majority, particularly in rural settings, the family of a victim of murder is entitled to receive monetary compensation, known as Diya, from the killer and his or her family. The Christian community was concerned that the practice could be forced on it. The community therefore asserted the secular character of the Chadian state and declared resistance to the extension of the Diya to other religious groups. According to existing laws, criminal sentence is individual and the friendly settlement of a crime according to cultural rules does not prevent the investigation and prosecution of the offence. The constitution also currently prohibits customary and traditional rules concerning collective criminal responsibility. Moreover, it provides that customary and traditional remedies may not impede public action. The Forum recommended that Diya be recognized in relation to members of communities that recognize the practice.

Concluding remarks: Old wine in a new bottle

Despite demands from the opposition, CSOs and the Catholic Church to submit the constitutional reforms to a referendum, the government decided to pass it through parliament, where the ruling party has the necessary supermajority to avoid a referendum. Opposition groups, the association of Chadian barristers as well as the Catholic Church, which has for the first time publicly taken position regarding the draft constitution, have claimed the illegitimacy of the current parliament considering that its mandate has been extended since June 2015 without fresh elections. Accordingly, only a referendum could ensure the legitimacy of the revisions to the constitution. Opposition members of parliament have accordingly boycotted the deliberations on the proposed revised constitution. Following the presidential promulgation of the constitution on 4 May 2018, a petition of 28 opposition parties requesting the revocation of the revised constitution was dismissed by the constitutional chamber.

For opposition groups, only a referendum could ensure the legitimacy of the revisions to the constitution.

At face value, the reforms could have significant implications to the way the state is governed, by decentralizing power vertically, while centralizing horizontal powers in the office of the president. Nevertheless, for the opposition, the first step must focus on changing the context, instead of the content of the constitutional text. In a context of a dominant president and ruling party, the changes are unlikely to lead to constitutionalism and effective changes on the ground. Opposition groups have therefore largely boycotted the reform process, instead calling for an inclusive political dialogue to address the myriad problems facing Chad. In the absence of opening of political space, the opposition are concerned that any new constitutional dispensation will merely lead to the continued submission of the country to autocratic presidential rule.

Dr Sioudina Mandibaye Dominique is a lecturer at the University of N’Djamena, Chad.