Making sense of Uganda’s stalled Age-Limit Bill

The recently proposed age-limit bill, which was ultimately rejected by the Speaker of Parliament, is a sign of coming struggles to protect what is left of constitutionalism in Uganda. Although brought as a private member’s bill, and seeking to raise only the retirement ages of judges and electoral commissioners, it was widely, and correctly, perceived as a first step towards undermining and eventually amending Article 102 (b) of the Constitution – to remove the presidential age limit.

Background

In August 2016, a few months after the Supreme Court affirmed President Museveni’s victory in the 2016 elections, a then little-known Member of Parliament, Hon. Robert Kafeero Ssekitooleko sought to introduce a Bill in Parliament that would seek, among other things, to raise the retirement age of Judges and to provide electoral commissioners with life tenure.

After a few weeks of intense debate, mainly in the public sphere, the Speaker of Parliament, Hon. Rebecca Alitwala Kadaga, decided against allowing the Bill to be debated. According to the Speaker, the Bill dealt with issues which would be more properly introduced by the Executive Branch in the context of a more comprehensive constitutional review process.

Placing the Bill in context

Although innocuous on its face, many followers of Uganda’s politico-legal history understood the Bill as yet another retrogressive step in the country’s struggle for a more just constitutional order, as it was seen as preparing the ground for a similar amendment for the presidential age-limit of 75 years – current President Museveni will be 76 at the time of the next scheduled elections.

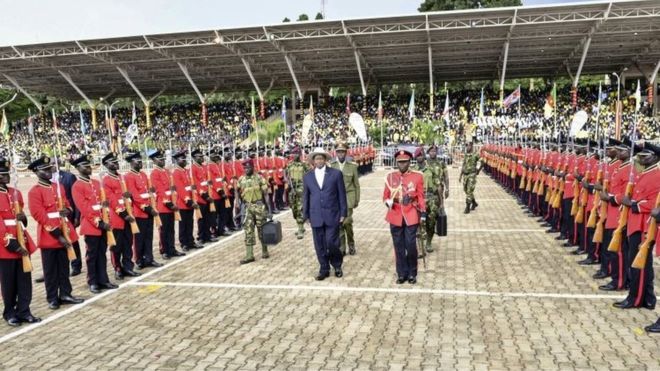

Uganda has the unhappy distinction of never having once, since obtaining independence from the British in 1962, witnessed a peaceful change of power, following popular democratic elections, from one President to another. Instead, the country’s history has been marked by a series of coups and counter-coups, prolonged conflict and civil strife.

It is this history that is captured in the Preamble to Uganda’s 1995 Constitution. In that Preamble, the Constitution is expressed to have been adopted by the people of Uganda, who did so recalling their history ‘characterized by political and constitutional instability’, recognizing their ‘struggles against the forces of tyranny, oppression and exploitation’ and committed to ‘building a better future by establishing a socio-economic and political order through a popular and durable national Constitution’.

Since that time, however, it has become clear that the country’s path towards constitutionalism and democracy remains difficult. Since the promulgation of the 1995 Constitution a number of safeguards against the creation and entrenchment an imperial presidency have been whittled down. This has been through the passage of a range of repressive laws such as those constraining the operation of civil society, restricting public assembly, and enhancing the capacity of the State to monitor and intercept communication. This has also been achieved through a range of extra-legal mechanisms that have increased the power of the military over civilian authority, undermined constitutional controls on expenditure of public monies and extended a broad blanket of surveillance over the daily activities of Ugandan citizens. However, the consolidation of presidential power was perhaps most starkly and expressly achieved by the amendment of Article 105 (2) of the Constitution, in 2005, to remove presidential term limits.

Ugandans recall very clearly that the removal of term limits was not done abruptly, but rather was preceded by a few sporadic calls for it early on in what should have been the President’s last term. They recall too that, leading up to that amendment, whenever the President was asked for his own views on that question he would simply say that he would ‘follow the Constitution’. In the event, of course, by the time the 2006 elections came up, the Constitution had been duly amended, and following it presented no great difficulties for the incumbent. Just as problematic as the amendment was the process leading up to the reform which was marked by the infamous ‘facilitation’ of each Member of Parliament with Ugx 5,000,000 (at the time approximately USD 1,750), to enable them to ‘consult’ with their constituents regarding the amendment.

It is in the context of this not-too-distant history that many Ugandans viewed Hon. Ssekitooleko’s Bill with a sense of déjà vu. Coming as it did from an as then relatively unknown Member of Parliament (rather than the Executive itself or a more established regime figure), and in targeting the retirement ages of Judges and Electoral Commissioners (rather than the Presidential age-limit directly), many observers recognized in this Bill the incremental approach that had been successfully employed in the early to mid-2000s to abolish presidential term limits.

In spite of the lack of formal connection between the Executive and Hon. Ssekitooleko, other than his belonging to the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party, there were a number of indications that the Bill was not as ‘private’ as it was presented. In the first place, prior to Hon. Ssekitooleko’s Bill, on July 4 2016, a conference of NRM leaders of Kyankwanzi district, led by the area Member of Parliament for Women and district NRM chairperson, Hon. Anna Maria Nankabirwa, passed a resolution calling for the removal of the presidential age-limit, and obligating all Members of Parliament from that region to work towards this end in the National Assembly. A few weeks, later, on August 1 2016, the President met with Hon. Maria Nankabirwa and the NRM leaders from Kyankwanzi. During that meeting, the President is reported to have received a copy of the July 4 resolution and was said to have thanked the delegation for that ‘wonderful gift’. He also said the matter would be debated by the NRM’s Central Executive Committee (CEC) and would be ‘looked at carefully’ before any decision as to ‘how to move forward’. It was following this meeting that Hon. Ssekitooleko and the ‘age-limit’ Bill emerged into the public space, inevitably triggering impassioned debate. Interestingly, the Bill appears to have been debated twice in Cabinet and, although in those meetings a decision seems to have been taken to reject it, it is reported that the government Chief Whip in Parliament, Hon. Ruth Nankabirwa (not to be confused with Hon. Anna Maria Nankabirwa above), appears to have actively mobilized NRM MPs to support the motion to have the Bill tabled. The fog around the Bill is thickened when one recalls that a little over a year ago, soon after her appointment as Chief Whip, Hon. Ruth Nankabirwa had affirmed her support for the presidential age limit, stressing that, after 75, ‘one must rest’. Hon. Ruth Nankabirwa’s evident support for the removal of age limits, after her apparent earlier rejection of them, mirrors that of the incumbent President, who would also be the major and immediate beneficiary of an amendment to Article 102 (b). Indeed, the President’s meeting with the proponents of the age-limit, and his gracious welcoming of their proposal came only one day after he had told reporters that any age-limit talk was ‘diversionary and idle’. In addition, it has been reported, although strenuously denied by Hon. Ssekitooleko, that in the tradition of the 2005 ‘facilitation’, certain inducements were offered to Members of Parliament on August 23 2016 in a bid to garner support for the Bill. Taken as a whole, the events surrounding the age-limit bill, especially in the context of previous means by which constitutional safeguards to a genuine and thriving democracy have been undermined in Uganda, it would be naïve to view the age-limit proposal as a simple act of a single Member of Parliament. Instead, it is more likely only one move of what are going to be a whole series of political chess moves, invariably having as their object the removal of the presidential age-limit under Article 102 (b).

The coming struggles

As noted above, the ‘rejection’ of the Bill does not in any way mean an end to the effort to eventually amend Article 102 (b) of the Constitution. Rather, the Bill may be understood as the starting shot marking the beginning of yet another round of struggles to protect one of the few remaining checks against a full blown imperial presidency. Indeed, the reference, during the rejection of the Bill, to the likelihood of more comprehensive reforms to be handled by a Constitutional Review Commission may point to a calculation that the amendment of Article 102 (b) may be ultimately be best effected under an omnibus bill, involving some moderate concessions to the opposition and other actors (including the judiciary and parliamentarians themselves). This would not be a new stratagem, especially when it is considered that the 2005 amendment of Article 105 (2) to remove term limits, was linked to ‘concessions’ permitting political parties to operate as such, after a long hiatus.

The struggle for true constitutionalism in Uganda is, therefore, very much an ongoing one. The challenge for those who would defend constitutional ideals, is that the threats to these ideals are today presented in more sophisticated terms, which appropriate the terminology and mechanisms of more progressive actors. Under this fashion, illiberal amendments to the Constitution are justified as exercises of popular sovereignty, and repressive laws are rationalized on the basis that more established democracies have similar enactments.

The Age-limit Bill, however, points towards an even more problematic and insidious development – the calculation that the amendment to the presidential age limit should be preceded by, or brought alongside – amendments to Judges’ own retirement ages, in a manner that makes the Judiciary’s own fortunes bound together with those of the President. It bears noting that, already, on account of the three decades long tenure of the current President, he has now appointed all present Justices of the Supreme Court; and most, if not all serving Justices of the Constitutional Court and Judges of the High Court. This reality alone presents real challenges for the legitimacy of the Judiciary in terms of its ability to act independent of an Executive at whose hip it now appears joined. The apparent stratagem to deliberately invoke judicial age-limits with the presidential age-limit appears aimed at not only further undermining the Judiciary’s legitimacy in this regard, but also practically making it difficult, in the event of a court challenge to the amendment, for the Judges to credibly decide other than to affirm the amendment relating to the presidency.

Dr. Busingye Kabumba teaches Constitutional Law and Comparative Constitutional Law at Makerere University in Uganda.