Liberia’s Constitutional Referendum on Dual Citizenship and Reduced Political Tenure

The referendum culminates years of participatory constitutional reform process, which over-promised but under-delivered. Critical proposals towards decentralisation, limits on presidential powers, and women representation were filtered through the political process. Moreover, the absence of proper civic education, lukewarm political support and combination with Senatorial elections may make the required two-thirds popular approval unattainable. Whatever the outcome may be, Liberia’s constitutional governance challenges would remain around longer - writes Ibrahim Al-bakri Nyei.

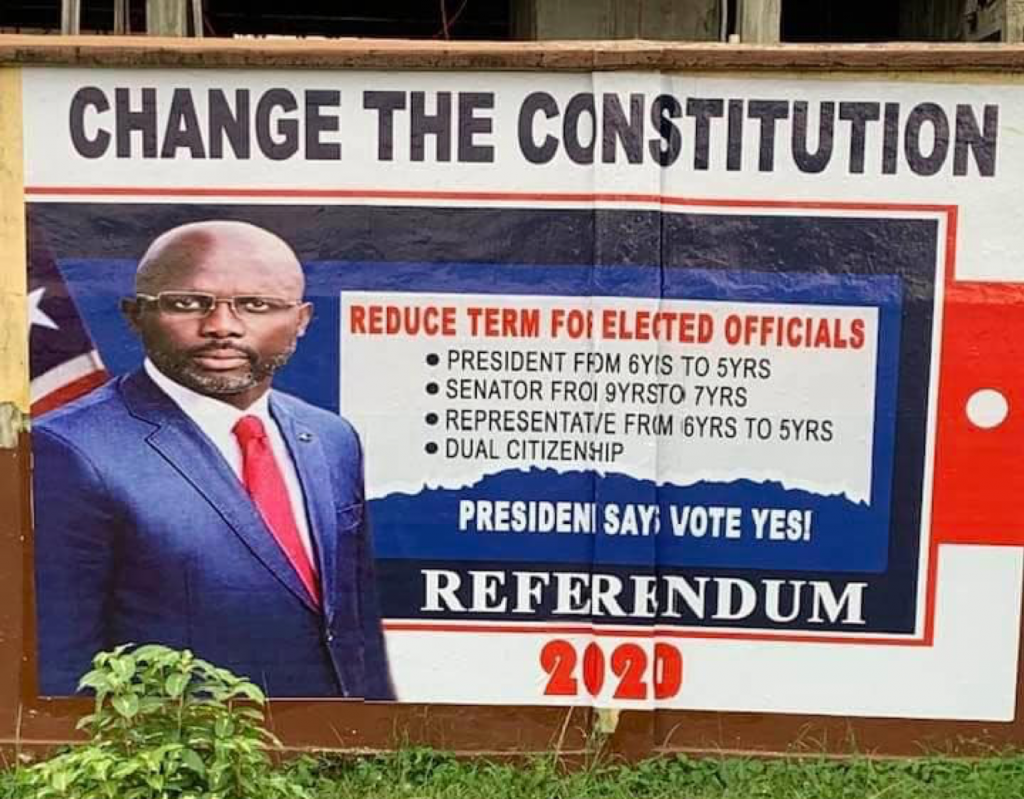

Liberians will in December 2020 go to a referendum to vote on proposed changes to their country’s constitution. If approved, the proposals would reduce the duration of presidential and parliamentary terms, allow double nationality, and change the timing of elections.

Adopted in 1986, the constitution was suspended several times during the country’s civil wars (1989 – 2003) to make way for extra-constitutional transitional governments formed at peace conferences. Proposals for a new constitution during the last transitional government (2003 – 2005) were poorly received by the warring and political factions and the international organisations that facilitated the peace process. Understandably, the stakeholders were preoccupied with efforts at disarmament and demobilization of armed groups and the return to civilian rule. But the failure to reform the constitution before the return to civilian rule in 2006 left a major aspect of the transition unaddressed and Liberians have yet to settle on a stable constitutional future.

The December referendum will be the second on changes to the 1986 constitution in a decade. When Liberians first went to a constitutional referendum in 2011, they voted on items negotiated among the political leadership—items more concerned with their electoral prospects and political future. One item, which failed at the referendum, sought to amend the residency clause for candidates that could have potentially disqualified the incumbent president and several politicians from the 2011 elections. A second successful amendment replaced the electoral system for the legislature from two-round majoritarian to the first-past-the-post. The other two unsuccessful items on the ballot concerned increment in retirement age of supreme court judges and change of the elections date.

Betrayal of public hopes

Unlike the first, this referendum follows years of public discourses and consultations on the constitution. It comes exactly eight years after the formal process of constitutional reform was launched with the establishment of the Constitution Review Committee (CRC). In its four years of existence, the CRC elicited views from Liberians at home and abroad at town hall meetings, expert seminars, and conferences, among a raft of methodologies meant to include as many perspectives as possible.

In the years following the 2015 constitutional reform conference, the political leadership plodded and tinkered with the outcomes of the exercise, but upon taking office in 2018 President George Weah — determined to reform Liberian citizenship laws — made constitutional reform a core priority of his administration. Weah’s enthusiasm energised activists who saw an opportunity in his support for dual citizenship to champion a wholistic consideration of the CRC proposals for the referendum.

For the champions of constitutional reform and the many Liberians who participated in the CRC consultations, they wanted a transformative constitutional reform exercise— one that leads to meaningful reorganization of the political order. Their proposals for reform, as collated by the CRC, sought to reorder power and authority relations, decentralize power to the counties and districts, reduce the excessive powers of the president, and provide for women and minority empowerment and political representation.

Liberians will go to the referendum on an extremely abridged version of publicly procured proposals.

These proposals are crucial to addressing Liberia’s perennial challenges with governance and social development. Beyond addressing marginalization and heralding a system of participatory democracy, they had the potential to upend the extensive networks of patronage relations which Liberian politicians rely on to advance their group and personal ambitions and sustain their power base.

Alas, they were rejected. Liberians will now go to a referendum in December on an extremely abridged version of the proposals and issues that speak less to their constitutional aspirations.

This referendum has three ‘Ballot Measures’ to be voted upon separately. Two crucial issues from the constitutional reform exercise are on the ballot — the proposals for dual nationality (Ballot Measure 1) and reduction in years of tenure of elected officials (Ballot Measure 2). These issues predate the launch of the CRC in 2012 and are perhaps those on which public aspirations on all sides converge.

Dual Nationality

Proposals for a dual citizenship legislation first emerged in 2007 but suffered several setbacks and have been a contentious political topic in Liberia since the end of the civil war. Natural-born Liberians in the diaspora who obtained citizenship of other countries (as a result of the civil wars back home) have been keen on regaining their Liberian citizenship, but cannot do so under current legislation. While they may be able to do so if a ‘Yes’ vote wins a majority on this item, they will face several restrictions in exercising their rights as citizens.

According to the proposition, a person holding dual citizenship will be disqualified from holding elected national or public service positions, as well as positions of chief justice and associate justices of the Supreme Court of Liberia, cabinet ministers and deputy ministers, heads of autonomous commissions, agencies and non-academic institutions, ambassadors, chief of staff and deputy chief of staff of the Armed Forces of Liberia.

Advocates of dual citizenship, mainly the Union of Liberian Association in the Americas, see these restrictions as ‘discriminatory’. They may have a point, but recent experiences with Liberians working in the public service and holding residency rights in foreign countries continue to put their loyalty to test. For instance, during the Ebola epidemic (2014-2016) a number of government officials with such privilege abandoned their responsibilities and fled the country leaving voids in the public service for several weeks. This experience, among many others, may have informed the inclusion of these restrictions.

Liberia’s citizenship controversy remains far from settled without a decision on the ‘Negro Clause’.

Nonetheless, Liberia’s citizenship controversy remains far from settled without a decision on the ‘Negro Clause’ that has been debated for many years. This referendum conspicuously omits the controversial proposal to remove this clause which restricts Liberian citizenship to only people of negro descent. This is particularly salient to people of Lebanese decent who were born or have lived in the country for many years, but do not enjoy citizenship rights. George Weah had initially pledged to support the removal of this restriction as part of strategies to open up the economy for more investments, but public resentment to this proposal, which made it potentially costly for his political future, may have forced him to back down.

Reduced Political Terms

The reduction in years of tenure of elected officials may be a silver lining between the aspirations of politicians and the public. During the CRC consultations, delegates proposed a four-year tenure for the president (down from six) and members of the House of Representatives (down from six), and a six-year tenure for members of the Senate (down from nine years).

Rather than rejecting this proposal outright, the political leadership accepted a modest reduction in their years of tenure for the referendum: a five-year tenure for the president and members of the House of Representatives and a seven-year tenure for members of the Senate. Some observers were left nonplussed that the political leadership accepted to reduce their own tenure, but others suggest this may be a ruse by the 53-year old President George Weah to reset the clock on term limits for a potential third-term bid.

Should Weah attempt to reset the clock on term limits, the courts would have to settle the issue.

Recent developments in Liberia’s neighbours where Presidents Alpha Conde (Guinea-Conakry) and Alhassan Ouattara (Cote D’Ivoire) are each vying for a third term after reforming their constitutions and the popular mantra among Weah’s supporters that they intend to rule for 24 years give credence to these suspicions. Nonetheless, it will be left to Weah to demonstrate his commitment or betrayal to Liberia’s constitutional principles of term limits for the office of president. There is no constitutional guardrail against such a move in the event of a constitutional amendment, but the constitution is clear that an amendment of presidential term of office ‘shall not become effective during the term of office of the incumbent President’. Should Weah attempt to reset the clock on term limits, it would require judicial review to settle that question.

Elections and Rain

The third ballot measure would change the date of elections from the second Tuesday in October to the second Tuesday in November and speed up the resolution of election disputes (by the National Elections Commission) from within 30 days to within 15 days. Liberia, unlike many other countries in the subregion — such as Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Cote D’Ivoire — has a constitutionally fixed elections date. A proposal to remove this fixed date for more flexibility within the election year has received very little enthusiasm.

The proposition therefore only seeks to change the date from October, a month of rainfall which stalls campaign activities, to November, when it is sunny enough and the usually deplorable roads to the interior are dry enough for politicians to easily navigate their way to campaign rallies. If this proposal is approved, it will reduce the financial and logistical burdens on politicians during campaigns, but at the moment, one can hardly point to any contribution it seeks to make towards a transformative democratic and constitutional future for Liberia.

An uninformed public?

While there are three ballot measures, the plebiscite will be held on eight articles of the constitution. How a population with an average literacy rate would discern these issues and make informed decisions remains to be seen. It is even more concerning that since the adoption of the referendum proposals in September 2019, there has been no civic education program on the items and voting process in the country.

This lack of public engagement is concerning considering that the three reform packages must be voted on separately and require a two-thirds majority approval of all the valid votes cast. A combination of low turnout and lack of information on the content and implications of the proposed amendments could undermine the chances of approval.

Plans by the National Elections Commission to conduct civic education (beginning October 30) on the voting procedures less than two months to the referendum may be useful to justify their performative bureaucratic requirements, but not sufficient to sensitize over two million voters on eight constitutional amendment proposals. If the evidence from the last referendum are anything to go by, this referendum may end up with a very high rate of invalid votes. In the 2011 referendum, despite several months of civic education and mobilization by the NEC and local civil society organizations, turnout was a paltry 34% of registered voters. Understandably, there was an average of 14% invalid votes across the four questions.

While the ruling party has launched a ‘Yes’ campaign, the opposition is yet to disclose their views on the proposed changes.

The lack of civic education programmes means that few Liberians occasionally talk about the referendum. Moreover, given that the referendum is being held alongside the Special Senatorial Elections of 2020, it lurks in the shadow of that election, which now dominates the public discourse. Besides the ruling Coalition for Democratic Change (CDC) which has announced it is campaigning for a ‘YES’ vote on all items, the main opposition Collaborating Political Parties (CPP) has yet to make any public declaration. Without broad political support, the two-thirds majority approval threshold may not be achieved.

The ruling party’s determination to have these changes seems inexorable, but they, like all political parties, are more occupied with winning more senate seats than engaging with this reform, which bears long term implications for the country’s constitutional future. They may succeed, but Liberia’s challenges with an extant constitutional order that facilitates marginalization, corruption, and over-centralization of power, and require constitutional reform will linger on longer than expected.

Ibrahim Al-bakri Nyei is a PhD student in Politics and International Studies at SOAS University of London. He tweets at: @ibnyei