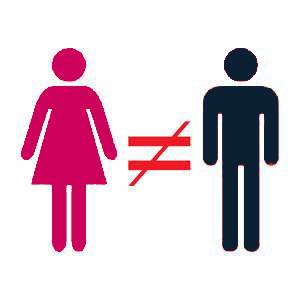

India’s failure to enhance the representation of women in national and state politics

India ranks among the lowest in the world in terms of the representation of women in politics. Successive efforts to address the imbalance through constitutional amendments have failed. Despite political consensus to enhance women’s representation, divisions among the major political parties make the adoption of the Women’s Reservation Bill unlikely – writes Sharma.

Background: Women on the constitutional bedrock

The issue of gender justice, affirmative action/quota for empowering women, has been a global phenomenon and India is certainly not an exception. No doubt, there has been formal removal of institutionalized discrimination, both at the constitutional as well as statutory and executive level. Yet, the mindset and attitude ingrained in the popular subconscious remain. Needless to mention, women still face several forms of indignity, prejudice and discrimination.

The Preamble of the Indian Constitution is like a key to open the mind of the makers as it invariably shows the document’s general purpose. The Preamble begins with the words “WE THE PEOPLE OF INDIA …” which includes men and women of all castes, religions, etc. It wishes to render “EQUALITY of status and of opportunity” to every man and woman. The Preamble further assures “dignity of individuals”, including the dignity of women. In line with these grand ideals, Indian governments have adopted several important laws pertaining to a range of issues, including family, succession, guardianship and employment, aimed at providing protection to the status, rights and dignity of women.

The Constitution of India not only grants equality to women but also empowers the state to adopt positive measures to address the cumulative socio-economic, educational, and political disadvantages women face. To give effect to these principles, the Indian parliament under the leadership of the Indian National Congress (INC) initiated constitutional amendments to require, among others, the reservation of not less than one-third of all elected seats in panchayats (villages and towns) and municipalities. A similar quota was established in relation to chairpersons in the panchayats. The amendments were initiated in 1991 and came into effect in 1994. The reserved seats may be allotted through a rotation system where only women candidates contest in a certain number of (reserved) constituencies, while (unreserved) constituencies are open to all candidates. The reserved and unreserved constituencies rotate in each election term. There are also provisions in state enactments that reserve the office of chairperson and the presidents in certain municipal corporations and municipalities, zila panchayats and janpad panchayats (district councils) for women. There are also initiatives from the current government to introduce constitutional amendments to increase the reservation from one-third to half of all elected seats in panchayats and municipalities.

From the local to the national: The pending Women’s Reservation Bill

Despite the reservation of seats at the local levels, there are no similar quotas in relation to elected seats at the national and state level. In practice, as well, the representation of women in the highest legislative organs has been nominal. Indeed, the representation of women in the national parliament has never exceeded 12.15% since independence. The representation of women in state assemblies is more dismal, currently standing at nine per cent. India ranks among the lowest in women representation in politics – 144th in the world. With a view to enhance the representation of women at the national and state level, successive governments since 1996 have unsuccessfully attempted to push through constitutional amendments establishing gender quotas. The proposals lapsed each time parliament was dissolved at the end of its term and were reintroduced by subsequent governments.

The latest effort has also stalled. The Women's Reservation Bill - the Constitution (108th Amendment) Bill, has been pending in the Indian Parliament since the United Progressive Party – a coalition of center-left parties including the INC formed after the 2004 elections – introduced it in 2008. The Bill proposes the reservation of one-third of all seats in the Lower House of Parliament (Lok Sabha), and in all state legislative assemblies (Vidhan Sabhas) for women, which may be allotted by rotation to different constituencies in the state or union territory. The seats to be reserved in rotation will be determined through lots in such a way that a seat shall be reserved only once in three consecutive general elections. Because members of Upper House of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) are elected indirectly, the focus and debate in relation to reservation of seats for women has remained mostly with regard to the election of direct representatives in the lower house.

Supporters of this Bill stress on the necessity of affirmative action to improve the condition of women. They claim that various studies on panchayats have shown the positive effect of reservation on empowerment of women and on allocation of resources. In contrast, the opponents of the Bill argue that it would perpetuate the unequal status of women since they would not be perceived to be competing on merit. They further argue that the reservation policy actually diverts attention from larger issues of electoral reforms, such as criminalization of politics and inner party democracy. India is already divided into various groups and the Bill may further divide the population artificially. Critics further argue that the reservation of seats in parliament restricts the choice of voters to women candidates and may undermine the nature and quality of debate in parliament. Furthermore, the rotation of reserved constituencies in every election may reduce the incentive for male parliamentarians to work for their constituencies, as they may be ineligible to seek re-election from that constituency. Some experts have suggested the adoption/promotion of alternative methods, such as reservation in political parties and dual member constituencies.

Status of the Bill: Another failed attempt

The Upper House of the Indian Parliament (Rajya Sabha) passed the Women’s Reservation Bill on 9 March 2010. However, the Lok Sabha has not yet voted on it. Despite the support from the main national political parties – the INC and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the Bill has not been approved due to opposition from male parliamentarians, mostly from regional parties of Hindi mainland in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The main demand of these regional parties who are opposing the Women’s Bill is to include a built-in quota for the Other Backward Class (OBC) and minorities within the women’s quota, i.e., they want caste-based reservation along with gender-based reservation.

The current President of India, Pranab Mukherjee, has called for renewed commitment to revive and approve the Bill. While inaugurating the first-ever National Conference of Women Legislators in March 2016 on the back of International Women’s Day, the President noted that, in the absence of a constitutional reservation, political parties are unlikely to dedicate one-third of their seats to women. The Bill also has strong support from many Indian gender rights activists as a precondition to create a level playing field for all citizens, and to enable more women to participate in politics and society, thereby increasing their opportunities.

Because both houses did not approve the Bill in the same parliamentary term, it needs to be tabled, debated and voted on again. If both houses were to approve the Bill, it would then have to be passed by half of India's state legislatures, and signed by the President of India. The long journey of the Women’s Reservation Bill has witnessed several difficulties in the Indian parliament. The battle for greater women representation in the Lok Sabha and state assemblies has been routinely delayed and sabotaged by frayed tempers and war of words amongst parliamentarians, which has sometimes gone to the extent of verbal abuse/ physical assault inside the Parliament.

What next for the Bill?

The Women’s Reservation Bill has opened up debate on the future direction of women’s empowerment in Indian politics. Whatever the theoretical arguments against the women’s reservation policy, in practice this policy will continue to be supported by all political parties (at least officially!) because of their own electoral advantages and professed commitment towards women empowerment. So far, the political parties have favored the Bill only to appease and entice their voters. Their non-serious and lackadaisical attitude towards women’s empowerment is evident in the fact none of the political parties has introduced the quota system within the party. Moreover, looking at the current parliamentary dynamics at the national level, the BJP center-right government enjoys an absolute majority in the Lok Sabha, while the INC, the main opposition party, has a majority in the Rajya Sabha. Both the BJP and the INC are officially committed towards the Bill. However, considering their deep divisions on a variety of issues, cooperation to pass the Women’s Reservation Bill remains unlikely.

No doubt, in the absence of gender equality and women empowerment, human rights remain in an inaccessible realm. However, despite constitutional safeguards, statutory provisions and a plethora of pronouncements to support the cause of equality of women, social attitudes and institutional bias remain entrenched. The Women Reservation Bill is certainly a positive step in the right direction. Nevertheless, while useful, laws written in black and white are insufficient to address the underlying causes. The limits of law necessitate concerted efforts to bring about institutional, social and behavioral change among India’s populace.

Avinash Sharma is an Advocate-on-Record, Supreme Court of India, and Visiting Faculty Member, Indian Law Institute, New Delhi. The author may be reached at <avinash.law@gmail.com>.