Constitutional and Governance Reforms in Sri Lanka: The road to the promised land

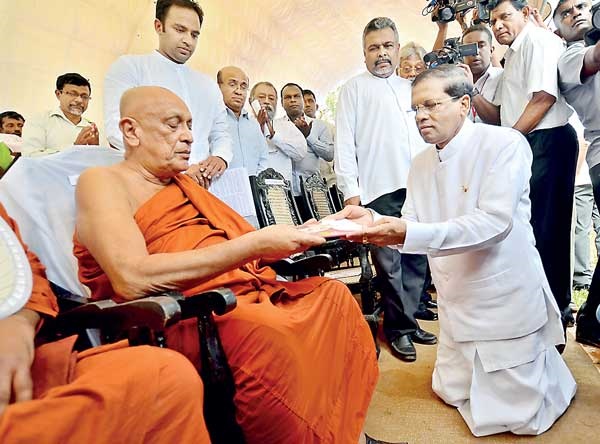

The Ven. Maduluwawe Sobhitha – the charismatic Buddhist chief priest who had provided the leadership to unite the civic and political opposition against the Rajapaksa regime – died after a brief illness on 8th November, generating an outpouring of genuine sadness across the country. Although he began his role in public life as a fiery socialist and Sinhala nationalist, in the last two decades he had become a moderate on ethnic issues and focussed his attention on campaigning for democracy, good governance, and a just political settlement for all of Sri Lanka’s peoples. When the common opposition mobilised by Rev. Sobhitha’s National Movement for Social Justice (NMSJ) defeated Mahinda Rajapaksa in the presidential election on 8th January, the thēra became the living embodiment of the adage that if the reactionary sections of the Buddhist monkhood had for so long been part of the problem, then its more enlightened and tolerant members could be part of the solution as well.

In the last few months of his life, however, this hero of the reform movement had become increasingly and publicly disillusioned at the slow pace and incomplete nature of the post-January reform process. He was scathing in his criticism that the executive presidency was not completely abolished by the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and he was appalled at the self-interested scheming within the political class that prevented a Twentieth Amendment reforming the electoral system. His death therefore removes from the scene a democratic visionary who inspired a nation across the ethnic and religious spectrum, and an influential advocate of not only constitutional reform, but also of the wholesale transformation of the culture and morality of politics. He could have provided a key check on any backslidings on reform promises as the ‘normal’ political process reasserts itself when the collective stimulation of the two historic elections of 2015 recedes from public memory.

It may have been the contrition elicited by the fact that these two central reforms were not enacted before the thēra’s death that prompted President Maithripala Sirisena to make a public vow in his oration at the state funeral to abolish presidentialism altogether before the end of his first term and introduce a new electoral system. In the days following, the President sought and obtained approval of a Cabinet Paper that recommitted the national government to these changes, although a need to re-establish his authority and mandate over his own Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) may also have played a part. After the parliamentary election on 17th August, the SLFP went into coalition with the United National Party (UNP) led by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe that had won the parliamentary majority, to form a national government. One of the principal rationales for this rare moment of cooperation between the two main parties is the need to secure the political consensus, and the necessary two-thirds majority in Parliament, to enact Sri Lanka’s third republican constitution. The coalition continues, but of late there had been rumblings of discontent among senior SLFP ministers about what they see as their subordinate status within a government that is dominated by the UNP. Despite provocative criticisms of his leadership from his own party members who remain loyal to former President and now Member of Parliament Rajapaksa, the President has remained true to his mandate and has constantly restated his commitment to seeing it through to fruition.

Over and above these ominous portents, however, since the general election there has been a growing sense of frustration in the country about the perceived inertia and lack of concrete progress in the constitutional reform process. The government was first preoccupied with co-sponsoring and redrafting the resolution of the United Nations Human Rights Council on accountability and reconciliation issues. What had promised to be an extremely critical resolution had the Rajapaksa administration been in power was transmuted into a much more conciliatory one through the cooperation of the new government. Nevertheless, the government has committed to a number of undertakings, including the establishment of a hybrid mechanism for the prosecution of alleged atrocity crimes, which are politically fraught in a country that remains by and large hostile to international intervention. The government’s focus then shifted to the equally if not more difficult issue of setting out an economic policy statement for the next few years and the presentation of its first full budget. Reforming the economy remains a challenging task, not only because of the need to set to rights the mismanagement and corruption of the Rajapaksa regime, but also because necessary retrenchment of the bloated public sector is always an unpopular policy path in a society that is accustomed to the state playing a significant role in the economic life of the community as a provider of jobs, hand-outs and subsidies.

Governance Reforms

Yet, there has been a lot of behind-the-scenes work taking place on setting up the independent commissions under the Nineteenth Amendment and other substantive reforms, as well as the process to be adopted in drafting and enacting the new constitution. The Human Rights Commission, the membership of which now includes competent and independent human rights lawyers, has outlined an ambitious programme of work, including a review of Sri Lanka’s existing obligations under international human rights law and accession to other instruments. The National Police Commission has conducted its first investigation into allegations of police brutality and made its first orders to the Inspector General of Police with regard to disciplinary action.

The draft Right to Information Bill will be presented for Cabinet approval next week with a view to presentation to Parliament early in the new year. This will provide the institutional apparatus to operationalise the new fundamental right to information introduced by the Nineteenth Amendment, including the establishment of a powerful new Right to Information Commission. Parliamentary officials have been developing sophisticated options for the reform of the committee system, and when implemented will significantly improve the institutional framework for scrutiny and accountability within Parliament. The convention that the two main financial oversight bodies, the Public Accounts Committee and the Committee on Public Enterprises, are chaired by opposition MPs has been re-established.

There will be party leaders’ consultations in December on the options for electoral reform, which may see agreement on a two or three tier mixed-member proportional (MMP) system that combines the best elements of first-past-the-post and proportional representation. While there is debate about the relative merits of the d’Hondt and Sainte-Laguë systems in the particular demographic context of Sri Lanka, there is broad consensus that the overall scheme of representation should remain proportional while restoring the connection between the voter and the representative through the reintroduction of first-past-the-post constituencies.

In January, party representatives and advisors to the President, Prime Minister, the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), and the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC), are scheduled to discuss the principles of a fresh devolution settlement that could be incorporated in the new constitution. The difficulties involved cannot be overemphasised given Sri Lanka’s 75-year record of failure in this regard, but at least, it cannot be denied that a workmanlike approach to devolution issues will prevail rather than the ideologically driven antagonisms of the past. The appointment of senior parliamentarian and leader of the TNA, R. Sampanthan, as the Leader of the Opposition in the new Parliament also has symbolic significance in this regard.

The National Secretariat for Media Reforms will publish in December a comprehensive review of the constitutional and statutory framework of the freedom of expression, together with far-reaching recommendations for policy and legislative action. The changes proposed encompass not only the rights framework but also the better regulation of the media to promote pluralism, transparency, professionalism, and accountability. If implemented fully, the report’s recommendations would make Sri Lanka’s freedom of expression environment one of the most progressive and open in Asia.

The Constitutional Assembly Process for the New Constitution

The biggest development in the path towards a new constitution, however, has been the publication of the draft resolution of Parliament for the establishment of a Constitutional Assembly (CA). Terminology is important: it is a ‘Constitutional’ rather than ‘Constituent’ Assembly because its purpose is only to draft the Constitution Bill and report thereon to Parliament, which retains its constituent power under the current constitution to enact the new constitution. Developed by the Office of the Prime Minister in consultation with expert advisors, the resolution articulates the CA mechanism, its rules of procedure, associated support institutions, the framework for public consultation, and the procedure for the legal adoption of the constitution through Parliament and a referendum.

The CA will be constituted under existing standing orders as a Committee of the Whole House, and the Speaker shall be its chairperson. Its purpose is defined in the resolution as “…deliberating on, and seeking the views and advice of the people, on a new constitution for Sri Lanka, and preparing a draft of a Constitution Bill for the consideration of Parliament…” The CA will be served by clerks, independent constitutional advisors and experts, external institutional services, a legal secretary, and a dedicated media staff responsible for sharing information, promoting public access to, and publicising the work of the CA. The CA will be divided into subcommittees, and its business will be led by a Steering Committee chaired by the Prime Minister, and consisting of the Leader of the Opposition, the Leader of the House, the Minister of Justice, and eleven other members. The CA is permitted to conduct its sittings in the chamber of Parliament, but it is also authorised to sit at any other location outside the Western Province. The Prime Minister has expressed the intention of the government to hold CA sittings in the ancient Sinhalese capital of Kandy as well as in Jaffna, the northern heartland of the Tamils. It is expressly provided that the work of the CA and its subcommittees would be open to the public, that their work would be documented and published, and where appropriate that its proceedings would be broadcast. The CA will have the power to invite any person for consultation or to make submissions.

The resolution also envisages the establishment of a Public Representation Commission (PRC) consisting of fifteen persons who are not MPs. The PRC is to solicit written submissions from the public through the mainstream and digital media, and to promote awareness of the CA’s work through the same media. It is to process public submissions and submit a final report to the CA within three months of commencing work, unless the time period is extended by the CA.

The resolution provides the general benchmarks of the process in drafting and enacting the new constitution as well as rules of procedure in some considerable detail. The subcommittees, whose subjects are to be determined, would report to the CA within ten weeks of their appointment. After consideration of these reports and the report of the PRC, the Steering Committee would submit its initial report to the CA, which may be accompanied by a draft text of a Constitution Bill. The CA will then debate the general merits and principles of this report, and invite the Steering Committee to submit a final report and a resolution containing the Constitution Bill. When the Steering Committee submits these documents to the CA after consideration of amendments proposed during the debate on general merits and principles, the Prime Minister is to move the CA to adopt the report and the Bill. The CA will then debate the Bill clause by clause, and amend or delete any clause. If at the end of this debate the Bill is not approved by two-thirds majority of the CA, then the process ends and the CA is dissolved.

If the CA approves the report and the Bill by a two-thirds majority, the Steering Committee would then submit the same to the Cabinet for approval, and the CA stands dissolved. The Cabinet would then certify the Bill as being a Bill to repeal and replace the current constitution, which is intended to be passed by a two-thirds majority of Parliament and the approval of the people at a referendum (in terms of Articles 75(b), 83, and 120(b) of the current constitution). The significance of adopting this particular procedure is that it completely ousts the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to entertain any legal challenge to the Constitution Bill. After the Cabinet certification, the Bill will be gazetted, and importantly, the President would refer the Bill to the Provincial Councils and seek their views (Article 154G(2)).

This provision seeks to protect the devolved powers of the Provincial Councils by ensuring they have a say in legislation affecting them. Its purpose is to ensure Parliament cannot impliedly amend devolved powers by ordinary legislation, but only by a two-thirds majority as for constitutional amendments. Parliament however can overrule any objections by one or more Provincial Council where it, as in the present case, intends passing the legislation with a two-thirds majority. The result is that while the Councils would have an opportunity to air their views – and it is hoped that they would use the opportunity to constructively but fully debate the Constitution Bill – they would not be able to block its passage. The pre-negotiated new devolution settlement that is to be part of the new constitution, and which it is assumed would devolve further powers beyond what is currently provided under the Thirteenth Amendment and strengthen devolution protections (e.g., through a reduction in the powers of Provincial Governors, a reformulation of concurrent competences, the introduction of a second chamber of Parliament, etc.) would therefore be critical in ensuring the accord of the Councils to the new constitution. The issue is far from academic. Some Provincial Councils are still controlled by SLFP majorities upon whose loyalty the President may not be able to rely. And most crucially, the Tamil-majority Northern Provincial Council is under the sway of a quixotic Tamil nationalist Chief Minister who is openly at odds with his TNA national leadership, and who may use this opportunity to embarrass them by disagreeing with the devolution settlement they would have negotiated within the CA process.

After the provincial consultation, the Prime Minister would present the Constitution Bill to Parliament. If and when Parliament passes it with a two-thirds majority, the President would submit the Bill to the people at a referendum. If and when the referendum approves the Bill, the new constitution would become law and come into operation at the appointed date.

The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Proposed Process

So how does the process outlined above compare with contemporary standards of democratic constitution-making? The major strength of the proposal is that it seeks to preserve formal constitutional continuity between the current constitution and its successor, while adding rules of procedure that incorporate an element of public consultation and a greater measure of legislative deliberation than is strictly contemplated in the existing procedure for the repeal and replacement of the constitution. The insistence on following a legal process would invest the new constitution with legitimacy and obviate extra-legal challenges to its authority. It would set a strong precedent that fundamental and radical constitutional reform can and ought to be undertaken by following due process.

In addition to the legality and legitimacy derived from following the established procedure for constitutional change and by ensuring Parliament is the main actor, the resolution outlines an unequivocally national process directed by democratically elected representatives. With that however also come the severe limitations of Sri Lanka’s political culture: the proclivity to ethnicise constitutional questions, extreme partisanship, unprincipled and tactical behaviour, and with only a few exceptions, the general lack of conceptual and technical capacity among MPs to undertake constitution-making. Moreover, the subcommittees, which would presumably have to study discrete aspects of the new constitution, have only two and half months to report on what are major and complex issues. The task of putting everything together into a coherent whole falls to the Steering Committee, which is likely to be controlled by the Prime Minister. The central institution for debating the draft in detail is the CA, which as a Committee of the Whole House is necessarily a large body of 225 members. As was illustrated during the enactment of the Nineteenth Amendment earlier in the year, this is not the best possible way to ensure the proper consideration of a Bill, with partisan point-scoring often becoming a substitute for legitimate disagreement and constructive debate (a problem that paradoxically may be exacerbated if the debate is broadcast live). This concern could to some extent be ameliorated if the CA debate is not hurried (only one day in the case of the Nineteenth Amendment), but unsatisfactorily, the resolution is silent about the number of days that are to be devoted to it.

More ambitious proposals for establishing a commission of national and possibly even international experts to draft the constitution and to conduct a much more extensive process of public consultations have clearly been rejected. While the PRC will play a role in promoting some form of public input into the proceedings, the process is clearly one that will be dominated by the elected Members of Parliament acting through the CA. Nonetheless, the public will have some opportunity to submit proposals during the CA proceedings, the Provincial Councils would have a say, and eventually, the referendum should at least notionally ensure that a wider public deliberation on the new constitution takes place. The referendum however is a take-it-or-leave-it proposition about the Constitution Bill as a whole, and a more elaborate framework for public participation during its making could have ensured more specific public involvement in the production of its content. The intensely political process, and the representative rather than participatory model of democracy that underpins it, will no doubt be criticised by some who would have liked an opportunity for the Supreme Court to make a legal pronouncement on the Bill.

Although not obviously apparent on a casual reading of the draft resolution, the overall consideration that seems to be foremost in the minds of both President and Prime Minister seems to be time. The substantive reforms being contemplated are so far-reaching and technically challenging that any constitution-making expert would have recommended a much longer process, perhaps the duration of the current Parliament. But time is the commodity that is in exceedingly short supply in the Sri Lankan process, at least in the view of its main political drivers, and it seems likely that the CA process would be completed as early as mid-2016, with the referendum to be held towards the end of the year. As noted, these short timelines would have inevitable consequences for the constitution-making process, and by extension for the substance of the new constitution. Cutting short debate and deliberation on design options and alternatives means that the best possible choices may not be made. The implications of comparative borrowings, to the extent they happen, would not be fully fleshed out and understood. Dominant actors like the Prime Minister, who have concrete ideas about what they want out of the process, are unlikely to be subjected to the critical scrutiny that is necessary to test the strength of their proposals, and it is unlikely the CA would have the time to consider the best possible range of competing advice from its advisors and make deliberative choices.

Two main factors have influenced the attenuated timeline, however, which are unlikely to be displaced: the first is the tenuous control of the President over his party in the context of the ever-present danger of Rajapaksa and his allies waiting in the wings to capitalise on failure. Secondly, the government is undertaking an inherently complicated constitution-making process in the context also of the challenges of taking action on human rights accountability issues and difficult economic reforms. Any one of these three sets of policy matters are challenging in themselves for any government to undertake; to do so simultaneously is nothing short of extraordinary. But we now know the government’s roadmap, which is on balance, defensible as a reasonable democratic process. Its success will depend on the continuation of the new national mood of republican participation that characterised the 2015 elections, and in this, the voice of social leaders like Rev. Sobhitha will be sorely missed.

Dr Asanga Welikala is Lecturer in Public Law at Edinburgh Law School and Associate Director of the Edinburgh Centre for Constitutional Law. He is also a Senior Research Associate of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), Sri Lanka.