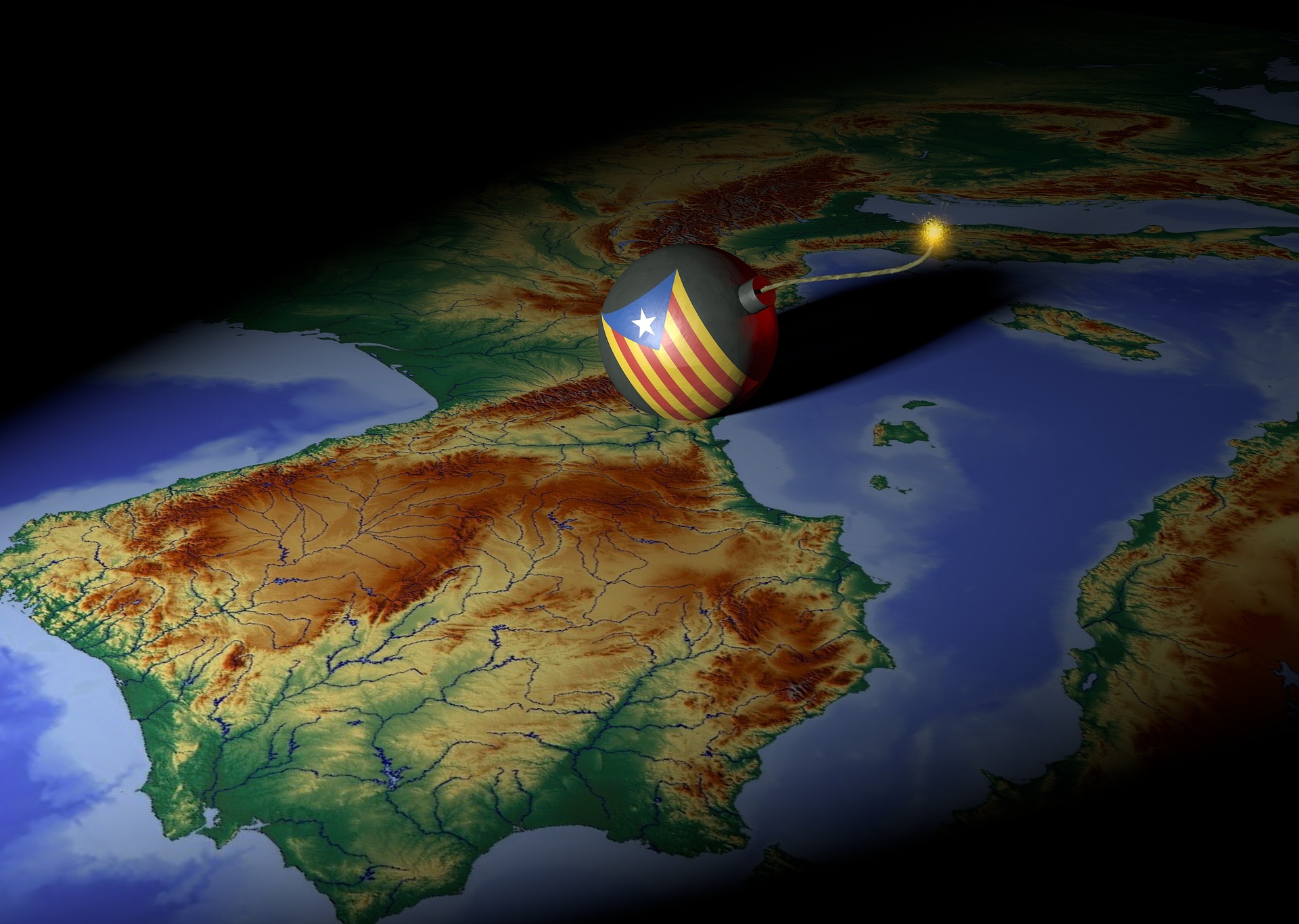

The Catalonia (constitutional) conundrum is here to stay

The temporary suspension of Catalan autonomy and the planned regional elections do not address the fundamental causes of the crisis. Constitutional reform appears to be the most plausible way forward. Nevertheless, political divisions and the difficulty of amending the Spanish constitution may hinder the process. If successful, constitutional reform would ward off the ghost of an ‘irreformable Spain’ and strengthen its legitimacy – writes Álvaro Imbernón.

On Friday 27 October 2017, the plenary session of the Catalan Parliament (Parlament) proclaimed unilaterally the independence of Catalonia from Spain based on the result of a non-constitutional referendum held on 1 October 2017, an unprecedented act in recent decades in Europe, beyond the context of the post-Soviet space and the former Yugoslavia.

Out of 135 MPs in the Parlament, 70 approved the independence declaration in a fast-track session with a debate in which not even the presidents of the parliamentary groups could speak, and with a secret vote in which the opposition did not participate. The whole process was marred by procedures disregarding the rights of opposition MPs and the decisions of oversight bodies in violation of the Catalan self-government charter (Estatut) and the Spanish constitution. In fact, this is a number of votes that would not be allowed to modify the Estatut or approve an electoral law (which require two-thirds or 90 MPs). The pro-independence parliamentary majority did not even receive the majority of the popular vote (around 48%). The image of a semi-empty Parlament made it clear that the narrative ‘Madrid vs. the people of Catalonia’ was not so clear-cut and that fissures exist within Catalan society itself.

The suspension of autonomy is temporary and does not include the full measures which are theoretically possible, since it does not apply direct rule to certain sectors (e.g. the Catalan public media).

The three main institutions of the EU, in addition to the United Nations and NATO, indicated unequivocally that they do not recognize the declaration of independence. Individual EU member states as well as major global actors such as the USA, Russia, and China, also did not recognize the declaration of independence.

The Spanish Government reacted by triggering the ‘nuclear option’ in article 155 of the Constitution, after the approval of the Senate, to restore ‘legality and constitutional order’. The party in the government, the Popular Party, but also Ciudadanos and the Socialist Party (PSOE) that represent around 3/4 of the Spanish Congress supported the measure, while the left-wing Podemos opposed it. The measures taken by the central government include the dismissal of all members of the Catalan government, the suspension of Catalonia's autonomy and the calling of regional elections in Catalonia for 21 December 2017. This is an interpretation of the article that does not include the full measures which are theoretically possible, since it does not apply direct rule to certain sectors (e.g. the Catalan public media) and limits its validity to a short period (until the day of the elections). Surprisingly, these measures have not led to serious tensions in Catalonia. The resistance of the independence movement or the Catalan administration has been very limited and the pro-independence parties have announced that they will run in the elections, this time without a joint list of secessionist parties. It is appropriate to note that article 155 is inspired by the ‘federal coercion’ provision in article 37 of the German Constitution. There are similar clauses in the constitutions of Italy (article 126), Austria (article 100), Switzerland (article 52), or Portugal (article 238).

The majority of Catalans prefer to continue within Spain after a negotiation with the central government.

The results presented by Puigdemont are devastating: a fractured society, more than 2.000 companies that have decided to move their fiscal headquarters out of Catalonia, zero international support and the loss of a vast self-government. A suicide, if we take into account that the nationalists monopolize most of the power in Catalonia (administration, civil society, media outlets) and, therefore, have much to lose. The current situation with part of the ceased government in prison and another part, with Puigdemont at the head, in Belgium makes it clear that the strategy was not adequate to approach its goals. In fact, many of the traditional narratives of Catalan nationalism suffer a much greater antagonism than in the past.

What next?

It is too early to speculate what the outcome of the forthcoming regional elections would be but everything indicates that the winning majorities will not be clear. In addition, judicial decisions can affect the political situation in Catalonia until 21 December.

What we do know is that Catalan society is deeply divided. The results of the referendum of 9 November 2014, the ‘plebiscitarian elections’ of 27 September 2015, and the (non reliable) figures of the referendum on 1 October 2017 coincide in that just under two million Catalans could be placed in the pro-independence bloc. This constitutes around 36% of the total of 5.3 million voters. The correlation of forces may have changed since the recent shocks have mobilized the traditionally apathetic electorate that rejects independence. A cursory look at the polls reveals that support for independence varies substantially but rarely exceeds 50%.

A new ‘non-permanent Commission for the evaluation and modernization of the State based on Autonomous Communities’ of the Spanish Congress is expected to start working on 15 November 2017.

In any case, the majority of Catalans prefer to continue within Spain after a negotiation with the central government. Given the risk of community division by mother tongue and family background (and even social class), it is imperative to think about long-term solutions. A binary and polarizing choice as pursued by the Catalan authorities does not reflect the Catalans' preferences for greater self-rule rather than independence, although most Catalans support a legal referendum on self-determination.

Constitutional reform appears to be the most plausible (and popular) way forward. The Socialist Party has indicated that its ambition to reform the constitution has been accepted by an extremely reticent Popular Party. For its part, Ciudadanos has supported this intention. The Basque Nationalist Party could join the project in the future. A new ‘non-permanent Commission for the evaluation and modernization of the State based on Autonomous Communities’ of the Spanish Congress is expected to start working on 15 November 2017. Unfortunately, the Commission is composed of 15 MPs from only three parties: PP, PSOE and Ciudadanos. The two major parties (PP and PSOE) have agreed that the commission will be limited only to evaluating territorial issues. It has six months to evaluate the autonomy model, nomenclature of the Autonomous Communities, distribution of competences, to analyze the 2010 ruling of the Constitutional Court on the Catalonia Estatut, fiscal arrangements, and local autonomy.

PSOE and its sister party in Catalonia, PSC, have proposed a federal arrangement.

The four priorities marked by the ‘Report on the amendments to the Spanish Constitution’ of the Council of State (2006) will be taken into account: Inclusion in the constitution of the denomination of the Autonomous Communities, suppression of the male-preference in the monarchical succession, inclusion in the constitution of the European integration process, and the reform of the Senate. The Commission is expected to propose recommendations for approval by the plenary session of the Spanish Congress, although the current political uncertainty creates doubts on the prospects. The real work will probably take place from January 2018 on wards after the Catalan elections. These recommendations would be the basis for constitutional reform and will probably be discussed later in the congressional constitutional commission.

PSOE and its sister party in Catalonia, PSC, have proposed a federal arrangement that ensures the recognition of the peculiarities of the different territories and a reform of the Senate that turns it into an authentic chamber of territorial representation (probably inspired by the German Bundesrat). A popular step could be the reform of the judiciary to enhance the independence of the General Council of the Judiciary and the Constitutional Court. Ciudadanos has also proposed non-territorial issues such as suppression of the privileged jurisdiction for MPs and senators and the inclusion of transparency and accountability provisions. It could also be interesting to consider the reform of article 99 to facilitate the investiture process to prevent gridlock when forming a government after inconclusive elections. For its part, the Popular Party has been very reluctant to any amendment and prefers to work on the proposals of the report of the Council of State, the body that consults the Spanish government.

Spain has only introduced two amendments to its constitution since 1978.

Some basic issues, such as including in the constitution the nomenclature of the Autonomous Communities and the recognition of the EU generate consensus, but regarding the rest the positions are very distant, especially taking into account Podemos and the peripheral nationalists. The extreme difficulty of reforming the Constitution can be seen in the fact that Spain has only introduced two amendments to its constitution since 1978, in both cases forced by petitions from abroad (to extend the active and passive suffrage right to EU citizens and to introduce a balanced budget rule).

An ambitious constitutional reform that includes the male-preference in the monarchical succession and changes in the rights of citizens would imply changing the ‘protected provisions’ of the Spanish constitution. Such a reform must be approved by two-thirds of the Congress and the Senate, after which parliament is dissolved; so it is likely that this reform would be carried out at the end of the legislative term. Once the new parliament is constituted, the amendment must be approved again by two-thirds of both chambers and ratified in a referendum. A more limited (and feasible) amendment based on territorial issues would need a majority of three-fifths of the members of each chamber. Even so, one tenth of the members of either chamber could request a referendum on the reform, which would happen in all likelihood. As such, it seems that if the amendment process would succeed in the parliament, it would still need a referendum.

If the economic crisis and the profound change in the party system have already been a great shock, the Catalan crisis can be a knock on the constitutional system.

In a context of extreme polarization and evident lack of institutional loyalty, it would be difficult to go along this complex process and to combine such diverse preferences hindering the scope of the reform. However, it would serve to ward off the ghost of an ‘irreformable Spain’ and strengthen its legitimacy bringing young Spaniards closer to their constitution by giving them the opportunity to vote on its reform in a referendum. Even so, the constitutional reform will only be a game-changer in case it is capable of incorporating peripheral nationalists, something that today in Catalonia seems a very arduous task. The objective should be to modernize the Constitution and not to reward those who operate outside the law. The reform will only be possible and successful if it is able to unite the will of most of the political arc. This includes a relevant part of the Catalan nationalists, without undermining the interests of the rest of the Autonomous Communities.

If the economic crisis and the profound change in the party system have already been a great shock, the Catalan crisis can be a knock on the constitutional system. Faced with unmet demands for reforms in recent years, constitutional reform could address the sense of discouragement and contribute to avoiding introspection. It is a long and winding road, but it is worth trying to cover it.

Álvaro Imbernón is an analyst at Quantio and an Associate Lecturer at Nebrija University, Spain.