Reconciliation Rejected: Is Constitutional Change Possible after the Voice Referendum in Australia?

In a significant setback for Indigenous peoples and their supporters in Australia, a long-awaited and highly anticipated constitutional referendum to establish a representative body to Parliament was soundly defeated. While state-level treaty negotiations are ongoing, the referendum outcome not only raises questions about the reconciliation process in Australia, but also casts doubt on the feasibility of any constitutional amendments within the current framework – writes Dr Harry Hobbs

Introduction

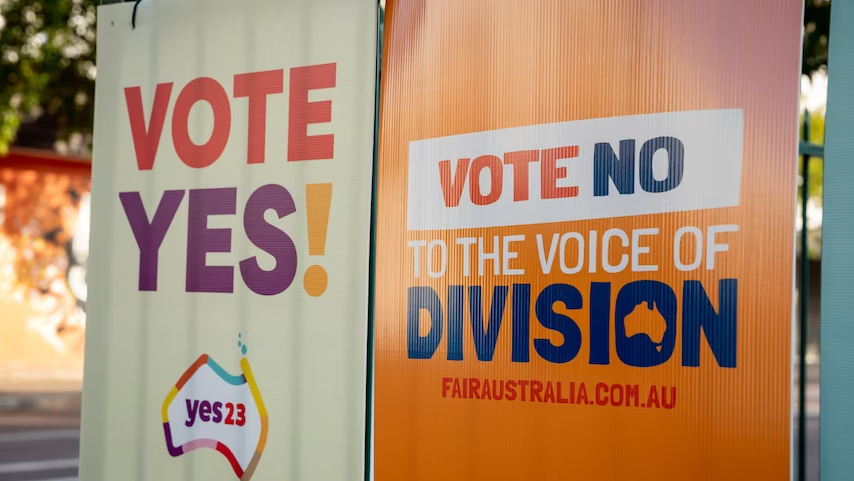

On 14 October 2023, Australians overwhelmingly voted against a proposal to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia. “The Voice”, as it was called, was envisaged as a representative body comprised of Indigenous Australians empowered to make representations to Parliament and the federal government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The idea emerged directly from Indigenous Australians, and was first presented to the Australian people in the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The defeat of the referendum raises two difficult constitutional issues. First, and most directly, the result ensures that the place and status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within the Australian state remains unsettled. Second, given that the Australian Constitution has not been amended since 1977, the result also calls into question whether the process of altering the Constitution has become too difficult. This piece will provide a background to the Voice referendum and subsequently explore these two issues.

A Constitutional Silence and a Democratic Challenge

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have inhabited the Australian continent for at least 60,000 years. While Indigenous Australians’ cultural and spiritual connection to the lands and waters of Australia is increasingly recognised in statute, common law and constitutional interpretation, the Constitution itself remains silent on this matter. The Constitution does not refer to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, let alone recognise their distinct rights and interests. The reasons for this omission are complex but can be traced to the initial encounters with British colonists. Rather than negotiate treaties that recognised the status and existence of the First Peoples, the British declared the continent ‘vacant’, and ‘without settled inhabitants or settled law’. Even today, no formal treaty has been negotiated.

This historical attitude influenced the development of the Australian Constitution and, indeed, the political and legal system that it established. One ongoing challenge is the capacity for Indigenous Australians – who comprise around four per cent of the population – to have their interests considered in the processes of governance. The ‘majoritarian arithmetic of electoral politics’ leaves Indigenous Australians ‘with little leverage over government decision-making’. The Voice was conceived to respond to this challenge in a manner consistent with Australia’s constitutional traditions.

The Voice Proposal

Since 2010, successive government and parliamentary inquiries have considered whether and how the Australian Constitution should recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Various proposals have been recommended, including a statement of acknowledgement in the preamble, a constitutional prohibition on racial discrimination, and a new section recognising Indigenous languages. These proposals failed to obtain broad parliamentary support and were set aside.

The dialogues identified the Voice as the desired form of recognition by Indigenous Australians.

In 2015, the federal government established a bi-partisan Referendum Council to revive the stalled national process. Led by its Indigenous members, the Council conducted twelve regional dialogues with Indigenous communities across the country in 2016 and 2017. These deliberative dialogues revealed that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples feel alienated from the processes of government. The dialogues identified the Voice as the desired form of recognition by Indigenous Australians. They explained that a Voice could be an empowering institution that would give Indigenous Australians a ‘greater say in government decision-making on matters that affect them and their rights’.

From 23 to 26 May 2017, the Referendum Council convened the First Nations National Constitutional Convention at Uluru, with delegates from the regional dialogues. The culmination of this convention was the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Grounded in their inherent rights as the ‘first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and adjacent islands’, the Statement called for a First Nations Voice to be enshrined in the Constitution and for the establishment of a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement making and truth telling. In the words of the Uluru Statement, these reforms would ‘empower our people’, remedy the ‘torment of our powerlessness’, and enable Indigenous Australians to ‘take a rightful place in our own country’.

The Uluru Statement called for “Voice, Treaty and Truth”, but Indigenous Australians emphasized that a constitutionally enshrined Voice was their first priority.

Getting to the Referendum

In 2017, the Liberal-National government dismissed the Uluru Statement and rejected the idea of constitutional reform. Nevertheless, under pressure to advance the call for a Voice, in 2019 the government declared that it would establish an Indigenous representative body in legislation. The Langton and Calma report into the design of this body was handed to government in 2021. It recommended a series of local and regional voices connected to a 24-member National Voice. However, the government did not progress legislation.

The 2022 election proved a decisive moment. While the Liberal-National government had moved haphazardly, the Labor opposition committed to implementing the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full. Consequently, the election of the Albanese Labor government put constitutional change on the agenda.

Wording of the Proposed Amendment

The precise wording of the amendment was recognised as key. Over the latter half of 2022 and the first half of 2023, the wording was finalised. This process was led by a 21-member Referendum Working Group of Indigenous leaders. The wording sought to meet several principles, including that the amendment be of benefit to and accord with the wishes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, be capable of being supported by an overwhelming majority of Australians, contribute to a more unified nation, and be technically and legally sound.

The Referendum Working Group’s wording was endorsed by the Parliament. The proposal would insert a new Chapter IX into the Constitution, which would consist of a single section 129:

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

- there shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

- the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- the Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

The wording made clear that the referendum would be focused on a single principle: whether there should be a Voice in the Constitution. Parliament would retain the authority to design, legislate and revise the operation and structure of the Voice. This two-step process is consistent with the Australian Constitution, which establishes many key institutions but leaves their detail and design to be worked out later by Parliament in legislation.

Several concerns were raised about the final wording. Some worried that the scope of the amendment was too broad, arguing that the Voice should only be able to speak on matters that directly affect Indigenous Australians. Others submitted that the amendment should not permit the Voice to speak to the Executive, fearing that the High Court of Australia may find an implication that statutory authorities and public servants must consult – and perhaps even adopt – any representations made. Still other concerns focused on the placement of the Voice in a new chapter of the Constitution.

Some proponents suggested that the government should establish the Voice in legislation so that all Australians could see how it operated, before taking it to a referendum . . .

Beneath these concerns lay a general sense that there was not enough detail on how the Voice would operate. Some proponents suggested that the government should establish the Voice in legislation so that all Australians could see how it operated, before taking it to a referendum. Others pointed to the Langton and Calma report, earlier national Indigenous representative bodies in Australia, and the Sámi Parliaments in Scandinavia as potential models – not always in favourable terms. Conscious of the failure of the republic referendum in 1999, however, the government reasoned that adopting a model may provoke more opposition. It nevertheless sought to thread this needle by releasing a set of design principles, but these did not quell concerns.

It is crucial to note that the vast majority of expert opinions considered the Voice legally sound. Former Chief Justice of the High Court, Robert French, argued the Voice was ‘high return against low risk’. The Commonwealth Solicitor-General explained the Voice, ‘is not just compatible with the system of representative and responsible government prescribed by the Constitution, but an enhancement of that system’.

The Difficulty of Amending the Constitution

Even if legal concerns were overstated, they were important because the Australian Constitution can only be altered via a referendum. The amendment requirement set out in section 128 reflects the constitutional principles of federalism and popular democracy. It provides that a referendum will only be successful if it achieves a ‘double majority’, that is, a majority of popular support in the country as a whole, and a majority of support in a majority of States (four out of six).

Constitutional change has proven hard. Former Prime Minister Robert Menzies described the challenge of securing an affirmative vote as ‘one of the labours of Hercules’, while some academics have labelled Australia ‘constitutionally speaking … the frozen continent’. These comments are not hyperbolic. Since the Constitution came into force on 1 January 1901, Australians have voted in 45 referendums, but only eight have succeeded.

What accounts for this rate? The most significant study of Australian referendums has identified four factors behind successful reforms: bipartisan support, popular ownership, popular education, and a sound and sensible proposal. Although this sounds straightforward, it has often proven elusive. Two key points stand out. First, Australians have little awareness of key features of and concepts underlying the Constitution. A similar pattern existed on the proposed amendment, with surveys persistently revealing that many Australians did not know much about the Voice.

Non-government politicians and political parties have found it hard to resist the urge to oppose referendums in the hope of gaining political advantage . . .

Constitutional illiteracy creates fertile soil for fear campaigns based on misleading and untruthful statements. In practice, non-government politicians and political parties have found it hard to resist the urge to oppose referendums in the hope of gaining political advantage. These two factors were significant in the referendum result.

In April 2023, the federal Opposition announced it would formally oppose the referendum. This decision denied the Voice bipartisan support. It also had the effect of turning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ request to be heard in the processes of governance into a proxy war between the two major parties, and polling indicates that support for the Voice dropped precipitously following the Opposition’s decision.

The Result, its Consequences, and What Happens Next?

The defeat was unambiguous. The Voice achieved less than 40 per cent support nationally and did not obtain a majority in any state. Although referendum scholars have noted the result is consistent with history, it has still sent shockwaves through the realms of public law and Indigenous affairs policy. It is too early to appreciate the long-term effect of the referendum, but two immediate consequences are visible.

First, even if polling suggested the referendum would fail, the defeat – and the campaign that preceded it – has been devastating for many Indigenous Australians. In the aftermath of the result, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders called for a week of silence and reflection. In an open letter published the following week, they declared the referendum had ‘unleashed a torrent of racism’, described the result as a ‘shameful victory’, announcing that the Constitution belongs to ‘white people’ and no reform that ‘includes our peoples will ever succeed’.

The result means the problem that the Voice was designed to resolve, the alienation and powerless felt by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, will persist. It also means that the larger constitutional issues will linger. Basic problems concerning the relationship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the State will remain unaddressed. Tragically, many Indigenous leaders who have dedicated their lives and careers to reconciliation now appear resigned to the fact that they will not live to see constitutional reform. In the words of Marcia Langton and Noel Pearson, right now, reconciliation efforts look ‘dead’.

The scale of the defeat also appears to have worried state governments pursuing complementary reform in Indigenous affairs at a subnational level.

The scale of the defeat also appears to have worried state governments pursuing complementary reform in Indigenous affairs at a subnational level. Frustrated by slow progress at the national level, from 2016 onwards several state and territory governments announced they would open conversations about treaty-making with Indigenous Australians. Today, every jurisdiction in Australia except Western Australia has committed to treaty-making with Indigenous peoples. The failure of the referendum complicates these developments.

The Queensland opposition has withdrawn support for the state treaty-making process, placing pressure on the state election next year. In New South Wales, the new Premier has also walked back plans after the national referendum. Nevertheless, the result may galvanise other jurisdictions. Victoria, which has made the most progress, has declared it will push ahead. As one former Victorian member of Parliament has noted, why should Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples be forced to ‘wait for a national process that has never ever delivered in relation to righting these wrongs’?

Second, the result also has broader consequences. The Australian Constitution has not been amended since 1977. No state has voted Yes since 1984. Given how this campaign played out, it is hard to see when it might be amended again. The Constitution is in need of reform. As befitting a document drafted in the 1890s, the instrument is replete with ‘out-of-date provisions and processes’ that produce ‘deadlocks, duplication and workarounds’.

At the same time, the challenge of securing constitutional amendment may pose challenges for the legitimacy of the document. The Constitution, like any law, derives authority from the ability of its subjects to reform it through legitimate means. If amendment becomes too difficult, what does this say about popular ownership of the Constitution? The Voice campaign reveals that there is a significant need for greater civics education. The referendum should be seen as an opportunity for government to invest in community education and constitutional literacy programs. Perhaps one consequence of the ‘No’ vote may be a more informed public. We can hope.

Dr Harry Hobbs is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Law at the University Technology Sydney

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Harry Hobbs, ‘Reconciliation Rejected: Is Constitutional Change Possible after the Voice Referendum in Australia?’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 26 October 2023, https://constitutionnet.org/news/reconciliation-rejected-constitutional-change-possible-after-voice-referendum-australia

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in Australia.