Mainstreaming Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA): Constitutional and Legal Reforms

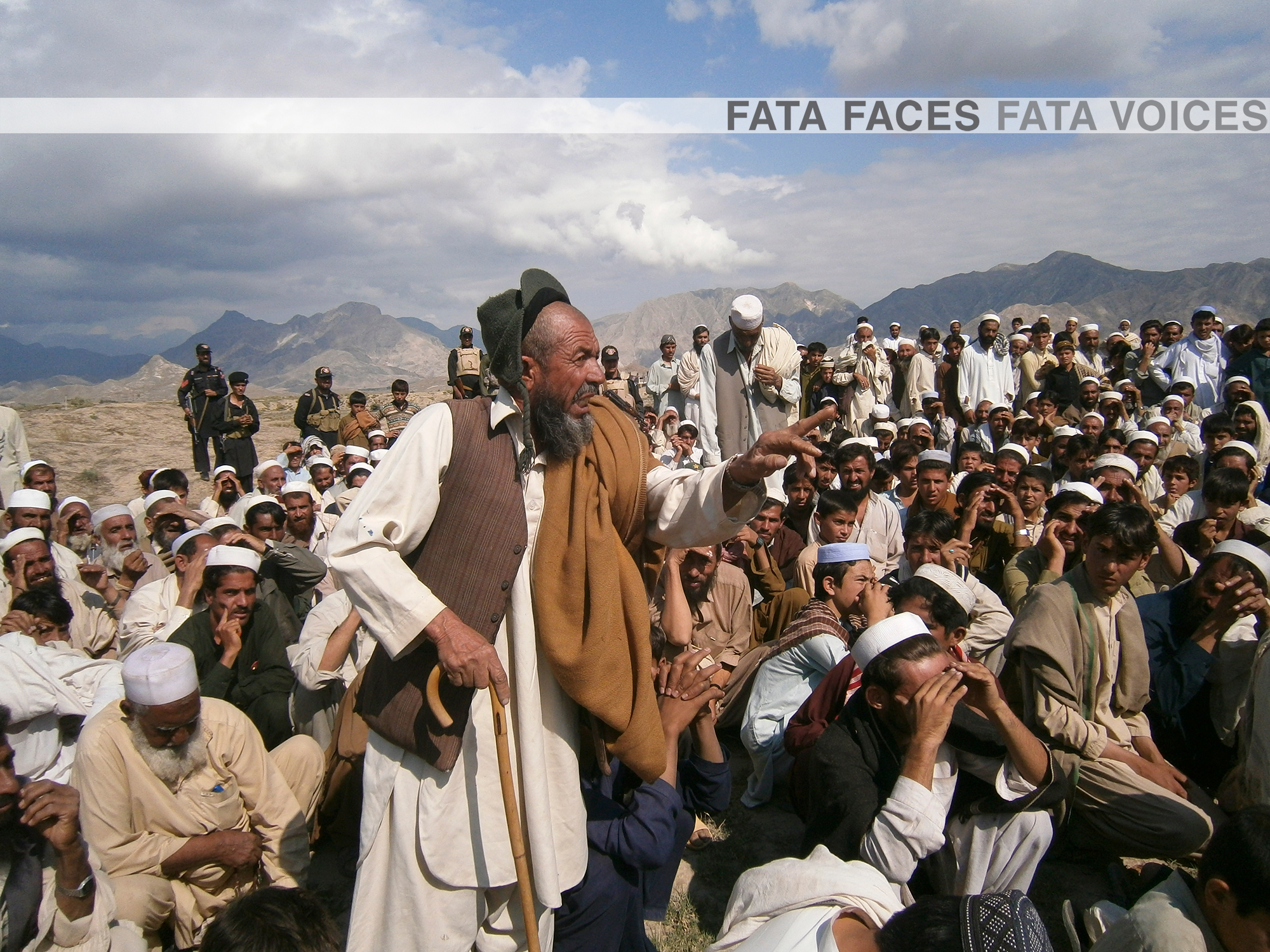

The proposed reforms seek to extricate the FATA from the legal black hole they currently occupy and to integrate them into the formal Pakistani constitutional, human rights, and legal framework, while allowing limited autonomy in dispute resolution through traditional systems. Nevertheless, despite improving the status quo, the reform process has not been inclusive of FATA and overrides some crucial aspects of indigenous mechanisms – writes Muhammad Zubair.

On 15 May 2017, the Government of Pakistan introduced two bills in the National Assembly (lower house of the parliament) entitled, the Constitution (30th Amendment) Act, 2017 (constitutional amendment) and the Tribal Areas Riwaj Act, 2017 (Rewaj Act) with the objective of mainstreaming and integrating Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) through merger with the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). The constitutional amendment bill proposes to increase the number of legislators in the KP Assembly from 124 to 147, giving representation to FATA with 23 additional seats. The Rewaj Act will repeal and replace the Frontier Crimes Regulation, 1901 (FCR), a 116 year old draconian British era law that continues to govern FATA. These bills were placed before parliament in pursuance of the recommendations of a government appointed committee, contained in the Report of the Committee on FATA Reforms, 2016 (the Report). The Prime Minister established the committee in November 2015.

Background

With an estimated population of 4.8 million people, FATA consists of seven tribal agencies (South Waziristan, North Waziristan, Kurram, Orakzai, Khyber, Mohmand and Bajaur) and six frontier regions (FR Peshawar, FR Kohat and FR Bannu, FR Lakki, FR Tank, and FR D.I. Khan), covering a large area along Pakistan’s northwestern border with Afghanistan.

Before the partition of Pakistan and India, the British colonial administration maintained, by and large, a policy of non-interference in the inter- and intra-tribe relationship in the areas comprising today’s FATA, but, in cases of conflict, the FCR regulated the relationship between FATA tribes and the colonial administrators. The tribes joined Pakistan after signing separate agreements of accession with the government of the newly formed state. The transition did not significantly change the status of FATA, which continued to be governed under the FCR. The FCR provides inter alia for collective punishment of a whole tribe or tribes for the offense of an individual tribesman or tribe against government, its personnel and property.

Each agency in FATA is headed by a political agent of the governor of the KP who has wide executive, judicial and administrative powers, enabling him to act in his discretion against persons and property of the tribesmen without being bound by any due process of law. He can order a blockade of a recalcitrant tribe or tribes, arrest and lockup tribesmen for any length of time even on a mere suspicion of the commission of crimes, impose any amount of fine on tribes, and demolish and destroy their properties in order to force their compliance, or simply as a punitive action. Such collective punishments have occurred during a decade long military operation in the areas, and the military has signed ‘agreements’ with the repatriating tribes apparently authorizing such measures in the future as well. No meaningful judicial recourse is available to the tribesmen under the FCR against administrative highhandedness of the political agent. In short, this law is against all judicial and human rights norms of a civilized society.

The 1973 Pakistani Constitution gives representation to FATA in the two houses of parliament, allocating 12 seats in the national assembly (MNAs) and eight seats in the senate. Prior to the introduction of adult franchise in FATA in 1996, FATA MNAs were indirectly elected by Maliks paid and designated by the government. The eight senators continue to be elected by FATA MNAs. However, FATA’s representation in parliament is meaningless because the federal legislature does not have ordinary law making power in respect to FATA. The constitution vests administrative authority over FATA in the national President who exercises it through the Governor of KP. The provision also bars direct application of laws made by federal or provincial legislatures to FATA, unless the President directs so, thus making him the sole legislative authority on FATA. The constitution also excludes the jurisdiction of the supreme and high court on FATA, unless an act of parliament extends it, which has never been done. The result is that, while the tribesmen theoretically possess fundamental rights under the constitution, they cannot enjoy those rights due to the absence of judicial protection.

As noted in the Report, in the last seventy years of Pakistan’s existence, the people of FATA and their representatives in parliament, civil society groups, and civilian governments from time to time have consistently called for pulling FATA out of the legal and constitutional black hole and bringing it at par with the rest of Pakistan. The state has however deflected these calls, ostensibly based on unverified claims that the tribesmen and women of FATA do not desire any change to their so-called ‘semi-autonomous’ status. The security establishment’s strategic paradigm – commonly known as ‘strategic depth’ – has largely dictated state policy towards FATA that would require keeping it as a ‘strategic backyard’ of Pakistan. The alleged lack of desire of tribesmen for autonomy, it is widely believed, has been presented as a pretext for resisting any legal and constitutional reforms that would dilute the status quo in FATA.

Incomplete constitutional and legal reforms

With this background, the proposed constitution amendment bills mark a fundamental break from the past. Three main benefits that the bills offer include the repeal of the FCR, the extension of the jurisdiction of the supreme and high court to FATA, and the representation of FATA members in the KP assembly. The repeal of the FCR and extension of courts’ jurisdiction will finally confer real citizenship status on the tribal people by recognizing as well as protecting their fundamental constitutional rights. As people of FATA and KP share the same language, culture, ethnicity and historical background, integration of the two areas is also seen to at least partially fulfil the historical demand of Pashtun ethnonational movements for the creation of a homogeneous province bringing together Pashtuns divided across KP, FATA, Baluchistan and Provincial Administered Tribal Areas. As the Report notes, as recently as September 2015, 19 parliamentarians from FATA had jointly moved a constitutional amendment for the integration of FATA with KP.

The Rewaj Act is also welcome in view of its claim that these reforms will not introduce an alien system of law but rather build the administration of justice in FATA on Rewaj (unwritten customary law) and Jirga (traditional and indigenous customary institution of dispute resolution). The tribes have lived under and regulated their internal relations from time immemorial according to Rewaj and Jirga. Despite the desire for reform, there has been a well-known resistance from FATA to the simple extension of Anglo-Saxon jurisprudential tradition of law, as reflected in legal codes and institutions of mainland Pakistan. The Rewaj Act promises to respect the wishes of the tribesmen by making their customary law and traditional institutions the building blocks in the process of mainstreaming FATA. Nevertheless, the application of customary law and procedure will be subject to judicially enforceable fundamental rights, which would ensure the protection of the rights of vulnerable groups, including women and children.

While these proposed reforms will improve the status quo, they fall short of the aspiration of people in FATA, and their stated objectives.

First, any meaningful ‘mainstreaming’ and integration of FATA with KP will be incomplete without the repeal of the constitutional authority of the federal government to exercise executive, administrative, legislative and judicial control over FATA. It also requires including FATA within KP’s territorial limits.

Second, with the retention of legislative and administrative control of the executive branch of the federal government over FATA, the proposed representation of FATA in the KP assembly will be meaningless as FATA legislators will not be able to legislate for FATA. It will be a replication of the position of FATA legislators in the federal parliament, which also cannot make laws for FATA.

Third, the extension of supreme and high court jurisdiction to FATA through the provisions of Rewaj Act – an Act of the parliament – implies that the federal government could withdraw that jurisdiction at any subsequent time. The availability and judicial protection of fundamental rights needs constitutional entrenchment, and cannot be left to the discretion of the government.

Fourth, the proposed Rewaj Act reinforces the federal control of FATA, where the federal government will have the power to: (a) appoint judicial officers who will resolve disputes amongst the litigants; (b) determine their powers and jurisdiction; (c) transfer a case from one judge to another judge; (d) make rules and regulations under the Rewaj Act; (e) remove difficulties arising out of the implementation of the Rewaj Act; and (d) empower itself where provincial governments normally have powers under the criminal and civil procedure codes. These powers militate against the autonomy of the FATA and their merger with KP.

Moreover, notwithstanding the claim in the Rewaj Act bill to ‘provide for retaining the Rewaj in accordance with the aspirations of the tribal people’, even the most favorable reading of the bill does not support that assertion. The drafters of the bill have identified two ways in which Rewaj will play a role in judicial proceedings: the selection of a ‘council of elders’ (Jirga) by a federally appointed judicial officer, and the council’s role in determining questions of ‘facts’ involved in criminal and civil cases according to Rewaj. While the bill also extends civil and criminal procedure codes, and evidence law to FATA, it gives Rewaj overriding effect over these procedural laws in case of conflict between the two. Nevertheless, the bill also extends 141 substantive laws to FATA over which Rewaj does not have such overriding effect.

As far as the appointment of Jirga or council under the bill is concerned, it is hardly different from the ‘officially appointed’ Jirga under the FCR, as opposed to the Jirga understood in the traditional and indigenous sense, which is selected by parties to the conflict for adjudication of their disputes. So, even in matters of procedure, the formation of Jirga under the bill is not according to Rewaj. The concept of Rewaj under the bill also conflicts in numerous other ways with the Rewaj in real sense of the term and this conflict arises mainly due to the drafters’ failure to make a distinction between the substantive and procedural aspects of Rewaj. The traditional Jirga is an egalitarian institution in which all parties to the conflict have the freedom to speak and arrive at consensus decisions in a democratic manner that usually result in a win-win situation. The bill introduces instead an adversarial judicial system whose decisions always result in winners and losers, which goes against the very grain of tribal traditions. The adversarial system starts the judicial process by ‘framing of issues’, whereas the Jirga proceedings are geared towards avoiding ‘framing of issues’, because it does not help in arriving at consensus decisions.

Finally, unlike the judicial system introduced in the bill, in Rewaj no distinction is made between civil and criminal cases. The traditional Jirga decides both procedural and substantive issues involved in a dispute, whereas the bill makes a distinction between the two. While apparently allowing Rewaj to override procedural laws, it – by implication – gives overriding effect to the 141 substantive laws extended to FATA, if there is conflict between the two. An example will illustrate it better: According to Rewaj, if the offender makes nanawate (appeal for mercy) to the victim’s family, the latter may forgive the former with or without compensation. But with the extension of Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) to FATA – which provides the punishment of death or life imprisonment for the offence of murder – in cases of conflict between the Rewaj and the PPC, the later will prevail. Lastly, the traditional Jirga decides both questions of fact and law, whereas the bill only gives the power of deciding questions of fact to the council of elders and empowers the government appointed judge to decide questions of law.

The lack of participation of FATA

The government driven reform effort has been an exclusive, elite driven process, happening mostly behind closed doors. None of the members of the reform committee belonged to FATA, apparently on the pretext that the neutrality of the committee required the exclusion of individuals from FATA. The Report claims that the committee visited all seven agencies of FATA and ‘held consultations with the Tribal Maliks, Elders, representatives of all political parties and other members of the civil society including traders, media representatives and … representatives of the frontier regions and Senior Civil Servants having FATA experience…’. Nevertheless, these mainly refer to closed-door consultations either amongst government selected and paid tribal Maliks or amongst retired civil/military bureaucrats. No meaningful participation of common FATA people – the real stakeholders – occurred. The Committee even failed to accommodate the unanimous demand of FATA parliamentarians for the repeal of the President’s special power over FATA. As such, the reform effort was not inclusive.

Due to these reasons, the FATA Political Alliance, and other groups, have termed the drivers behind the reform, i.e., the non-FATA elite group of bureaucrats and political figures, as stepping into the shoes of long-gone colonial masters who set themselves on the mission of ‘civilizing’ the tribal Pashtuns by recommending ‘for them’ a set of alternative constitutional, legal and judicial reforms in which ‘they’ do not have any input. It hardly needs an argument to show that public participation in the making of constitutional and ordinary law that affect their lives in fundamental ways is extremely important. Public participation lends democratic legitimacy, ownership and ensures stability. Sadly, the common tribesmen and women do not figure anywhere in the reform debate.

Concluding remarks

Overall, the proposed changes seek to integrate the FATA into the formal Pakistani constitutional, human rights, and legal framework, while allowing limited autonomy in dispute resolution through traditional systems. Despite the indicated shortcomings, the constitutional and legal reform package is a significant improvement on the status quo. The reform proposals were tabled by the governing coalition, enjoy the support of the major opposition groups, and the apparent blessing of Pakistan’s powerful military establishment. Even those who oppose it primarily call for more consultations. Crucially, according to a recent survey, despite the lack of consultations, almost three quarters of FATA residents support merger with KP and the repeal of the FCR.

Nevertheless, whether the proposed bills will see the light of the day before the present government’s term completes in 2018 is uncertain. Indeed, the consideration of the bills was postponed reportedly on the demand of the two coalition partners of the federal government, i.e., PkMAP, a Pashtun nationalist party, and JUI(F), a religious party popular in Pashtun areas. Considering their support base in Pashtun constituencies, it is strange and confusing why these parties would stall the government’s reform agenda for FATA while all opposition parties have welcomed it despite its shortcomings.

Despite the lack of consensus between the opposition and government parties on almost every other political issue, surprisingly all opposition parties and the ruling coalition – except its two smaller coalition partners – are on the same page as far as FATA reforms are concerned. The federal government has come under severe criticism for stalling and backtracking on the reform process from both inside and outside parliament. Given the consensus amongst political parties, support of the military establishment and the overwhelming demands of civil society and the tribesmen and women, FATA reforms cannot be delayed for much longer.

Muhammad Zubair served as Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Peshawar, Pakistan. He is currently a PhD Fellow at the Maurer School of Law, Center for Constitutional Democracy at the Indiana University Bloomington.