The Latest Attempt at Charter Change in the Philippines: Prospects and Concerns

The Philippine Congress recently passed a resolution paving the way to convene a constitutional convention. Proponents argue that amending "economic provisions" in the Constitution will attract foreign investment, while critics cite the lack of empirical evidence for this claim and potential exploitation of natural resources and Indigenous lands. Amid opposition from the President, Senate, and business community, questions emerge about the ambiguous motivations for invocating a convention with an undefined mandate. Can heightened public awareness influence the future of this process? – writes Dante Gatmaytan

Introduction

The Philippine Constitution is 36 years old. It was adopted in 1987—a year after Ferdinand E. Marcos was deposed as president. Marcos was elected into office two times. When his second term was about to end in 1973, he maneuvered an ongoing constitutional convention that resulted in a shift to a parliamentary form of government in the 1973 Constitution, allowing him to assume leadership of the country as prime minister. Marcos stayed in power for almost 21 years under various constitutional configurations until the People Power Revolution resulted in his exile in 1986.

After the revolution, the 1986 Freedom Constitution was promulgated, followed by the current 1987 Constitution, which (re-)established a presidential system of government. Now, almost 40 years later, on 14 March 2023, lawmakers passed a bill with an overwhelming majority of 301 to 7 with no abstentions. This resolution, which awaits passage by the Senate, paves the way for the convening of a constitutional convention and has reopened the contentious debate on the wisdom (or not) of amending the fundamental charter.

Previous attempts to amend the Constitution

This is the latest attempt of many to amend the Constitution. Almost every post-Marcos administration has made such an attempt, but none have been successful. Previous attempts to amend the Constitution were anchored in creating a unicameral system of government—an effort that understandably met resistance from the Senate.

There were other attempts to amend the Constitution that barely concealed the goal of lifting term limits. Civil society and the political opposition were alert to these designs and managed to thwart these attempts by politicians to stay in power.

In public consciousness, campaigns to amend the Constitution are now equated with attempts by elected officials to perpetuate themselves in power . . .

In public consciousness, campaigns to amend the Constitution are now equated with attempts by elected officials to perpetuate themselves in power—a response to Marcos’ successful replacement of the fundamental charter in 1973.

More recent attempts to amend the Constitution are, as the present one is, ostensibly designed to amend or remove “economic provisions” of the Constitution. The argument posits that certain provisions of the Constitution, such as those restricting ownership of certain industries to Filipinos, deter foreign investments.

Issues and Concerns

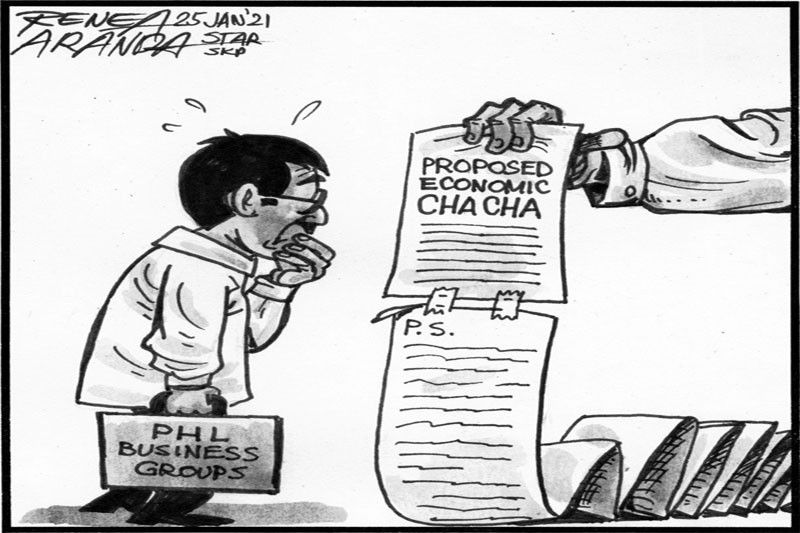

The latest attempt at amending the Constitution is not without its own set of concerns. First, neither the President nor the Senate has expressed support for any campaign to amend the Constitution. The President said that constitutional amendment was not his priority, while the Senate President, as of writing, has stated that the project is a waste of time as the Senate does not have the needed votes to pass it. He also said that the amendment will derail the enactment of priority legislative measures. Second, business groups have urged lawmakers to reconsider their bid for a constitutional convention, saying that it is a “potentially disruptive proposal” that may drive away investors and mute the gains of the government’s economic reforms. Third, proponents of constitutional amendments cannot point to any study supporting the view that certain provisions of the Constitution deter the inflow of foreign direct investments.

Fourth, the proposal calls for a “hybrid” constitutional convention because there would be a combination of elected and appointed delegates. However, a hybrid constitutional convention does not conform with the Constitution, which provides that, “Any amendment to, or revision of, this Constitution may be proposed by: (1) The Congress, upon a vote of three-fourths of all its Members; or (2) A constitutional convention.” Amendments can also be proposed via citizens’ initiative.

The framers of the Constitution understood that the delegates to a convention would be elected and not appointed . . .

While the Constitution is so broadly written that it does not appear to prohibit a hybrid constitutional convention, the framers of the Constitution understood that the delegates to a convention would be elected and not appointed, as this exchange between Commissioners from the Records of the Constitutional Commission on 9 July 1986 shows:

MR. MAAMBONG: I am following up the sponsor's answer that when we talk of constitutional convention, we are talking of elective delegates to the constitutional convention. In other words, it negates the authority of the legislature to just name delegates to the constitutional convention without calling an election.

MR. SUAREZ: That is very obvious, Madam President.

MR. MAAMBONG: Thank you, Madam President.

Since the legislature could not name delegates without calling an election, it also goes without saying that the legislature cannot delegate the power to somebody for that authority to name delegates to the constitutional convention?

MR. SUAREZ: The Gentleman is right.

There is nothing in the Constitution that suggests a constitutional convention can be filled by appointment: a hybrid convention will therefore certainly invite litigation.

Fifth, there is no definition of “economic provisions” in the Constitution. So while supporters of constitutional amendment may be thinking of restrictions on the ownership and management of mass media, the operation of public utilities, and the practice of all professions (all of which have restrictions in the Constitution), the fact is that a constitutional convention can extend other parts of the Constitution such as the extent of the participation of foreigners in the extraction of resources.

Presently, Article XII on “National Economy and Patrimony” contains restrictions on the participation of foreign corporations in the extractive industry. For example, part of Article XII of the Constitution reads: “The State shall protect the nation's marine wealth in its archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and exclusive economic zone, and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens.” The Constitution also allows the president to enter agreements with foreign-owned corporations regarding the development, extraction, and utilization of minerals and oil. The Convention, in theory, may opt to open the exploitation of the Philippines’ marine wealth, the territorial sea, and the exclusive economic zone to other countries. It may also open small-scale extraction to foreign corporations.

Amendments could water down protection of the rights of Indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands . . .

Amendments could water down protection of the rights of Indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands, presently protected in the same Article on “National Economy and Patrimony”. Section 5 obliges the state, with carve outs for national development policies, to “protect the rights of Indigenous cultural communities to their ancestral lands to ensure their economic, social, and cultural well-being.” Further, Congress “may provide for the applicability of customary laws governing property rights or relations in determining the ownership and extent of ancestral domain.”

A heartless constitutional convention, oblivious to the colonizers’ history of oppression of Indigenous communities, could remove the recognition or protection of ancestral domains to facilitate corporate intrusions into these lands. Foreign and local corporations may be given easier access to natural resources within ancestral domains.

In short, amending “economic provisions” of the Constitution is not a benign crusade that simply attracts investments: it could be used to open up Philippine resources to foreign corporations at the expense of protecting the rights of marginalized Filipinos as presently mandated by the Constitution.

Conclusion

It is too early to say if this latest attempt to amend the Constitution will succeed. There is a possibility that those feigning disinterest are simply testing the waters to gauge public support for the project. When it becomes evident that there is little popular resistance, political players may express support for the amendment project. When the interests of the political players align, the amendment process will no doubt move faster.

The lack of empirical evidence to justify removing economic limitations fuels views that these are a pretext to opening the entire Constitution to change. Politicians, however, do not seem to care. The near-unanimous vote in the House of Representatives calling for a constitutional convention indicates two things: first, there is no meaningful political opposition to speak of, and second, there is little critical thinking that can be expected from elected officials. Unless the public is properly apprised of the implications of amending the Constitution, they are not likely to be more critical than their elected representatives. If the people swallow the narrative crafted by the House of Representatives—that the goal of this project limits its Charter amendments to the “restrictive” economic provisions of the basic law “in the hope that the changes would pave the way for the country to attract more foreign investments”—then there is a possibility that they will blindly ratify any proposal that will come from the constitutional convention.

Dante Gatmaytan is a Professor at the University of the Philippines, College of Law.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Dante Gatmaytan, ‘The Latest Attempt at Charter Change in the Philippines: Prospects and Concerns’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 31 March 2023, https://constitutionnet.org/news/latest-attempt-charter-change-philippines-prospects-and-concerns

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in the Philippines.