Guinea-Bissau’s political paralysis: Potential and risks of constitutional reform process

Despite the recognised need for constitutional reform, new President Embaló’s establishment of an independent constitutional reform commission has been criticised as modifying legally prescribed process for constitutional change. Although the commission’s work is expected to be submitted to the National Assembly, given the political context, caution is necessary to ensure that the process of constitutional reform does not exacerbate political tension – writes Dr Ibrahima Amadou Niang.

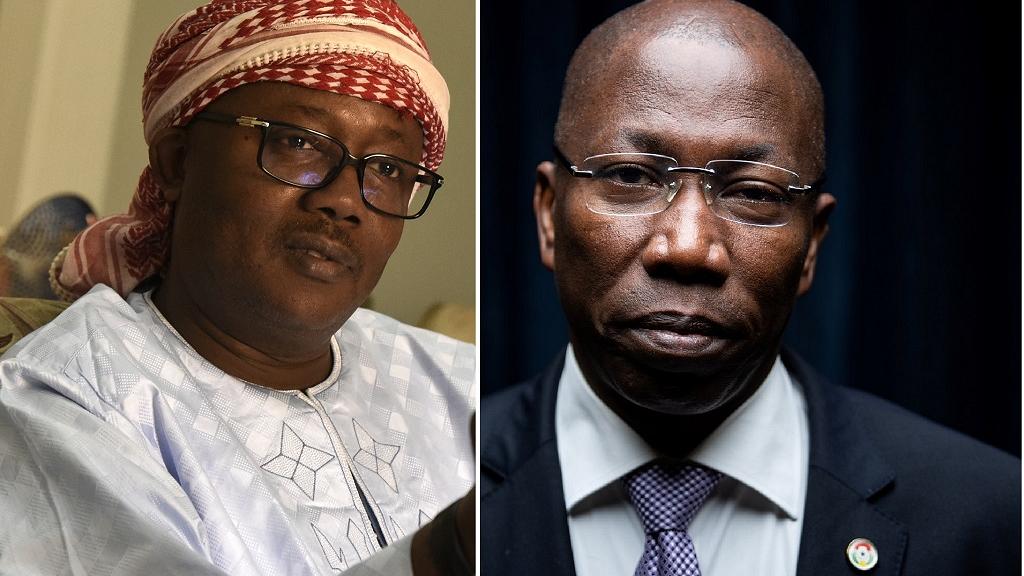

In May 2020, President Umaro Sissoko Embalo, whose victory is still contested, established an independent commission to draft a revised constitution with a view to primarily reform the semi-presidential system of government that has consistently precipitated political stalemate. The commission consists of two former presidents of the country’s Supreme Court and three jurists and lawyers and is supported by a technical team. It is expected to propose constitutional changes to allow the execution of the Conakry Accord reaffirmed in Lomé in April 2018.

While constitutional reform has been accepted in past political dialogues as critical, the unilateral pursuing of the effort will face challenges without the buying-in of the opposition in the National Assembly and could exacerbate the political paralysis.

Background

Guinea Bissau has been reeling in a wave of political crises since 2015 following contested presidential elections in May 2014, which were hoped to end a cycle of coups, instability, and political assassinations. The elections brought to power José Mário Vaz from the historically dominant African Party for the Independence of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde - PAIGC. In August 2015, Vaz dismissed Prime Minister Domingos Simões Pereira, who was leading PAIGC, following apparent personal differences. The dismissal effectively split the ruling party. Siding with Pereira, parliament re-nominated him for the premiership, which Vaz rejected. The appointment of another high PAIGC official as prime minister was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, as under the semi-presidential system established in the constitution, the prime minister is selected based on ‘electoral results’ and after consulting political parties represented in parliament.

Despite the paralysis, Vaz went on to become the first president, elected or not, since independence to finish his term, a reflection of the historically high level of political instability. The country has been spared recurrent coups mainly because of the presence and the active involvement of the Economic Community of West-African States (ECOWAS), which also maintains an armed mission in the country (ECOMIB).

Vaz is the first president to finish his term, indication of recurrent political instability.

The first major breakthrough in terms of political agreements, the Conakry Accord, was signed in October 2016, following dialogue involving political stakeholders, representatives of religious groups and civil society organisations. The Accord included, among other things, a call for constitutional reform based on wide consultations and through established procedures aimed at constituting stable relations between the executive, the legislative and the judiciary, and reform of the electoral law. ECOWAS and the UN undertook to avail the services of high-level constitutional experts. A subsequent Lomé Agreement (April 2018), ECOWAS’ extraordinary summits and ultimatums have helped the country navigate arduously through these difficult times.

New elections, continued instability

Despite the March 2019 parliamentary polls and a highly contested presidential election, which incumbent President Vaz lost, the political paralysis has continued with a post-electoral crisis between winning candidate Umaro Sissoko Embaló and runner-up Domingos Simões Pereira, the PAIGC candidate, who rejects the results of the presidential election.

Embaló, whose inauguration is still under dispute, wants to initiate major constitutional reforms towards a system of government better fitting the socio-cultural reality of the country and enabling institutional stability. Although there is no doubt on the need for reform to provide structural solutions to Guinea Bissau’s political challenges, uncertainties remain as to its appropriateness in the current context and the legality of the chosen path.

Unstable semi-presidential system

Since the advent of the multiparty system in 1991, instability has been recurrent owing to the heritage of the national liberation struggle, the semi-presidential system of government, constitutional ambiguities, and the role of the military in politics. Despite being liberated by the same party as Cape Verde – PAIGC, the democratic fortunes of the two countries could not have been more different.

Notably, Guinea Bissau’s semi-presidential system of government with a powerful prime minster has induced instability. Under the constitution, the President of the Republic appoints the Prime Minister considering the results of parliamentary elections (article 98) and can dismiss parliament in the event of a serious political crisis (article 69 (a)). There is lack of clarity on the exact division of powers between the president and prime minister. Under article 96, the government led by the prime minister is the highest executive and administrative body, while under article 103, the government is politically accountable to the President and to the National Assembly.

ECOWAS has recommended the drafting and adoption of a new constitution through referendum.

This ambiguity has fuelled recurrent conflicts between the President on the one hand, and the Prime Minister and Parliament on the other hand. As a result, since the first multi-party elections in 1994, no President except for Vaz has ever completed their term in office. Even Vaz had eight prime ministers in five years. In fact, the country has been in standstill the last three years of his term with parliament barely functioning. Added to this is the murky relationship between the army and politics. Several senior army officers were PAIGC members, and have maintained relations of complicity and interest with politicians.

All these factors led the outgoing President (Vaz) to plead for ‘a constitutional reform which allows the elimination of the sources of institutional instability and the clarification of the system of government to avoid future political crises’. This is in line with a strong recommendation of ECOWAS to draft a new constitution to be submitted to a referendum in six months (by October 2020).

An atypical constitutional amendment process in West Africa

Despite the recognition of the need for reform, Embaló’s approach has been criticised because it is said to deviate from the constitutionally prescribed process for reform. Under the Constitution, the initiative for constitutional reform solely belongs to at least one third of members of the National Assembly and requires a two-thirds approval for their passing, without need for referendum. The President does not have the authority to propose amendments or veto them.

Embaló’s decision has particularly surprised members of a parliamentary constitutional review committee in operation since 2007, as the commission effectively duplicates their work. They have stressed that in the light of the fundamental law of Guinea-Bissau, the parliamentary committee should take the lead in the reform process. As chairman of the committee, Rui Diã de Sousa has invited the authorities to submit to the country’s laws and work through his team. However, Embaló attempted to clarify the situation during the commission’s inauguration where he declared ‘we all know that the constitutional review initiative is the responsibility of the MPs and not the President’. He added that ‘the commission will present a draft revision of the Constitution for subsequent submission for discussion and adoption by competent bodies’.

Embaló would do well to continue reassuring all stakeholders that he will work with the National Assembly to launch an agreeable process of reform.

To the extent the work of the commission is expected to complement the formal amendment process, it could be defensible. The establishment of expert commissions to complement formal amendment processes has increasingly become a common practice across the West African region and in Africa.

At the time of establishment of the commission, some observers thought that Embaló wanted to bypass parliament controlled by the PAIGC (47 out of 100 seats). The parliamentary composition has recently evolved in Embaló’s favour as five PAIGC MPs voted for the new government giving him a majority in parliament. Nevertheless, PAIGC still have the numbers to block any constitutional reform as these require a two-thirds majority. Accordingly, Embaló would do well to continue reassuring all stakeholders that he will work with the National Assembly to launch an agreeable process during the work of the technical commission as well as once it has completed the work. Without such engagement the constitutional debate could exacerbate political tension.

To ensure constitutional continuity, Embaló should keep his promise of referring the outputs coming out of the work of the Commission to parliament to start the normal constitutional amendment process. Moreover, although a referendum is not constitutionally required, it may still be considered to legitimize constitutional reform enacted through the constitutionally provided procedure.

Political blockades

The political and post-electoral crisis continues to divert attention from structural solutions to the crisis. The question of constitutional revision, even if it is of paramount importance for the implementation of the series of political agreements, has struggled to build momentum in the current context. Although ECOWAS has officially recognized Embalo’s victory and demanded the formation of a government based on the results of the 2019 parliamentary elections, PAIGC continues to challenge Embaló’s legitimacy as well as that of his government. The two ‘coups de force’, i.e., Embalo’s inauguration without final pronouncement of the Supreme Court on post electoral disputes and the dismissal of Prime Minister Aristides Gomes (PAIGC) who was in office before Embaló’s inauguration, have complicated the political tensions.

A political settlement on both the contestations over the electoral outcomes and an agreeable constitutional reform process may be necessary.

With a large part of the population and PAIGC refusing to recognize the new President, they are unlikely to participate in any constitutional reform process. Given the political trajectory of Guinea Bissau and the historic role of certain civil and military actors, a non-inclusive constitutional reform will not enable the structural resolution of political crises and institutional instability.

It may therefore be necessary to seek a comprehensive path forward through a political settlement on both the contestations over the electoral outcomes and an agreeable constitutional reform process to reform the government system that has been at the root of the recurrent political paralysis.

ECOWAS’ central role

The development of such a comprehensive pathway may require extensive involvement of ECOWAS, which has been critical in the management of the Guinean Bissau crisis. ECOWAS has insisted on the importance of working on a new constitution by October 2020 but has not expressed a position regarding the establishment of the constitutional review commission.

ECOWAS could prioritize the stabilization of political power through a compromise between the various actors, the establishment of an inclusive government, and agreement on a blueprint for constitutional reform. To ensure sustainable institutional stability, constitutional reform will have to be carried out in a relatively peaceful environment, according to a process under the seal of legality and legitimacy. Moreover, the long-term effectiveness of this reform may also require the revival of the national reconciliation process as well as State and Security Sector reforms.

Dr Ibrahima Amadou Niang is an author and political scientist based in Guinea. He is specialized in political transitions and democratization processes.