On the fragility of new democracies: Tunisia between constitutional order and disorder

Tunisia is at a crossroads: return to parliamentary democracy or sink into authoritarian rule. As a first step, the President has appointed a new government, but it is also necessary to set a date for legislative elections. Moreover, the President must clearly outline his intended amendments to the political system and the electoral law, and ensure a transparent and inclusive reform process. The President's next steps, therefore, will allow us to judge the sincerity of his commitment to constitutionalism and parliamentary democracy – writes Nidhal Mekki

A transition is never a long, quiet river, just like the consolidation of the democracy that emerges from it. The current situation in Tunisia clearly confirms this. The only country to ‘survive’ the Arab Spring, Tunisia is now at the crossroads of two completely opposite paths: return to parliamentary democracy or sink into authoritarian rule. Is it any wonder that things have come to this? Not really. The crisis that precipitated this situation, previously analysed on ConstitutionNet, has been simmering for months. The central failure to establish the Constitutional Court, which would resolve conflicts about interpretation of the Constitution between the powers involved, has made it impossible to find a legal solution to the country’s constitutional and political crisis. All this, combined with an unprecedented economic crisis aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic, has created not only disruption in the normal functioning of state institutions but a real risk of the collapse of the Tunisian state.

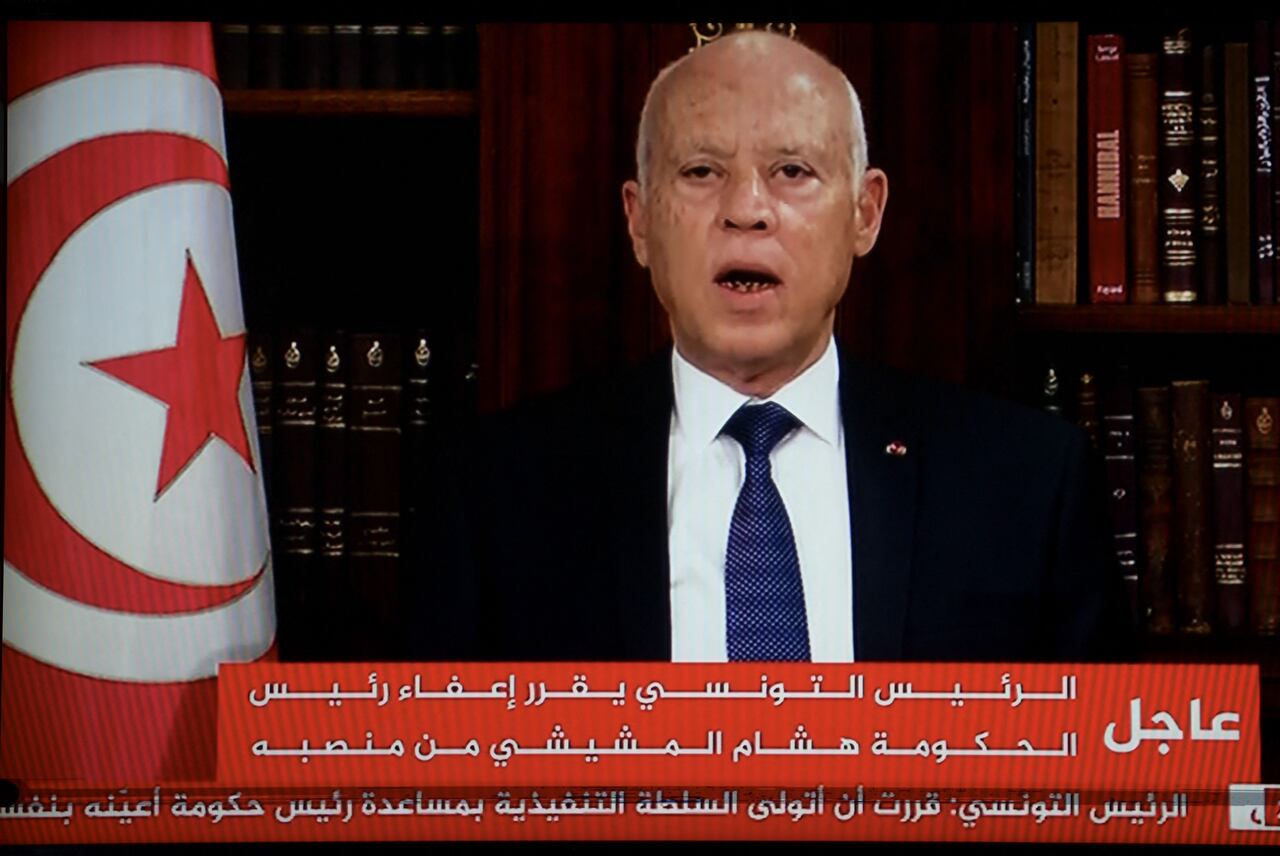

There was an urgent need to act and this is what the President of the Republic decided to do on 25 July 2021 by resorting to emergency powers under Article 80 of the 2014 Constitution, dismissing the government and freezing parliament. This use of Article 80 has raised heated debates among political and academic elites and civil society and has sparked condemnation from the international community. This piece analyses the President’s invocation of emergency powers and stresses the importance of returning Tunisia to constitutional order.

The President’s use of Article 80 of the Constitution: between legality and legitimacy

The 2014 Constitution (like many modern constitutions) provides for and frames the Head of State’s recourse to exceptional measures in very specific circumstances. President Kais Saied was therefore legally within his rights to resort to Article 80 depending on his assessment of the "imminent danger" that threatened the state, its security, or its independence and that might prevent the normal functioning of the state's machinery.

Article 80 uses rather vague language, so the interpretation of “imminent danger” needed to trigger the article, in the absence of clearer guidelines, is therefore the sole responsibility of the President. The prescribed consultation with the Head of Government and the President of the Assembly of People's Representatives (APR) is a formality that the President says he respected, but which did not bind his decision. As for informing the President of the Constitutional Court, as required under Article 80, the question is moot since this Court has not been established.

This is how the President decided to suspend all the prerogatives of the parliament, lift parliamentary immunity, dismiss the Head of Government, some ministers, and the head of the Public Prosecutor's Office (which he later retracted).

Despite the contention that the President's use of emergency measures under Article 80 is justified in principle, one of the President’s measures is in direct contradiction to Article 80. Indeed, according to this article, during a state of exception, the APR is in a state of continuous session and expressly cannot be dissolved. Hence, it appears that the President has violated the Constitution.

Tunisia has moved from a "legal moment" to a "political moment," where legal analysis cannot explain the events nor chart a return to a constitutional order…

Some observers noted that on 25 July Tunisia moved from a "legal moment" to a "political moment," where legal analysis is not only unable to explain the course of events but cannot propose a way out of the crisis and a return to a constitutional order. We must bear in mind that one of the reasons that led to 25 July was the total erosion of the APR's popular legitimacy. As opinion polls have shown, the unstable parliament had become the most hated and despised institution among Tunisians. This partly explains the largely positive public reception of the President’s actions, but the reactions of the political parties were mixed. Government coalition parties (Ennahdha, Qalb Tounes and the Al Karama coalition) fiercely opposed the measures, describing them as unconstitutional and a coup d'état. They further called for the restoration of parliament and even for the trial of the President. Other parties adopted a more nuanced position, highlighting the political responsibility of the ruling coalition parties for the crisis that brought the country to a standstill, while asking the President for solid guarantees of a rapid return to constitutional order. Some other parties (notably Achaab) openly support the President's actions and consider them necessary.

If we borrow a metaphor related to the cosmos, the use of Article 80, even if it was- partially contrary to the letter of the Constitution, allowed us to remain in the "internal solar system." We moved a little away from the sun (the Constitution), but we remained in a zone where the force of gravity of our star was still quite strong. This state of affairs changed on 22 September 2021.

The presidential decree of 22 September 2021: from a state of exception to an attempt to fundamentally reorganize public power?

After 25 July 2021, the fear of a leap into the unknown led political forces, civil society, and international organisations to warn the President of the Republic against monopolizing power. Further, some of the country’s most influential jurists called for a return to parliamentary democracy and respect for the Constitution.

On 22 September 2021, the President surprised everyone by issuing a presidential decree that de facto sealed his grip on the executive and legislative branches. This presidential decree is in clear violation of the 2014 Constitution, but it is important to note that the current constitutional framework (albeit partly suspended) is decisive for understanding the scope and effects of the decree. Article 20 of the presidential decree clearly states that "The preamble of the Constitution, its first and second chapters, and all constitutional provisions that are not contrary to the provisions of this presidential decree, shall continue to be applied”. Other citations reference the Constitution as a whole, and in particular Article 80, the preamble, and Article 3. In addition, Article 22 states that "The President of the Republic shall prepare draft revisions relating to political reforms..." It is clear from the latter that the President’s intention (at least as of now) is to prepare draft revisions to the Constitution, not to replace it.

Some of the provisions of the 22 September presidential decree are a source of legal problems, fears, and political risks, the danger of which should not be underestimated.

That said, some of the provisions of the 22 September presidential decree are a source of legal problems, fears, and political risks, the danger of which should not be underestimated.

The suspension of the APR was extended via the decree, which in practice means dissolving the parliament without saying so explicitly. But what arouses the most apprehension among jurists, political forces, and civil society is the fact that the presidential decree concentrates executive and legislative powers in the hands of the President, without any safeguards and for an indeterminate amount of time. Some jurists have observed that the link with the 2014 Constitution has become merely "nominal" and that this decree is a disguised Provisional Organization of Public Powers, like Tunisia experienced between 2011 and 2014 and which, precisely, governed the country while it was without a permanent Constitution. If we want to use the solar system metaphor again, we would say that we are now, with this presidential decree, in the outer solar system with the gravity of the sun, the 2014 Constitution, getting weaker and weaker.

A trip to the constitutional universe of President Kais Saied

President Kais Saied himself once said that he sometimes thinks he is from another planet because he does not recognize himself in the practices of political parties. We will therefore try to make an excursion in the constitutional universe of the President's mind in order to draw the contours of the revisions to the Constitution that he will likely propose. Based on the President's statements during the election campaign and many of his speeches throughout his two years in office, it seems the President’s intended reforms will revolve around two main areas: the political system and the electoral law.

Regarding the former, the President has made his views known on numerous occasions. The main feature of the regime he advocates has "one master on board" because he believes that the “system of three presidencies” (of the Republic, the government, and the APR) is not suitable for Tunisia. A President of the Republic, always elected by direct universal suffrage, will likely enjoy great popular legitimacy and will be able to take strong decisions without the political dithering and incoherence that characterized the country for ten years. This would be a return to the spirit of the 1959 Constitution, for which the President has never hidden his partiality. Article 8 of the presidential decree may foreshadow the status and role of the head of government in the future plans of the President: limited to assisting the President in the exercise of executive power and accountable to the President. The President has also frequently mentioned his reconceptualization of power and the representation of the general will in the political system. According to the President, this will mean moving towards more local and direct democracy through the election of local councils that will deliberate on public affairs and then take their decisions to the national level.

The President has long proposed a uninominal voting system with small constituencies, combined with a recall procedure to increase accountability.

This point necessarily leads us to the President's vision of the electoral law. Indeed, for the President, a model based on political parties, especially as practiced in Tunisia, has led to distance from the will of the people. According to the President, political parties serve their own partisan interests and impose on voters sometimes corrupt and often incompetent politicians (an opinion shared by one of the country's most eminent constitutional experts). As a potential antidote to this situation, the President has long proposed a uninominal voting system with small constituencies. This would allow voters to elect candidates whom they know personally and whose integrity they can assess. In addition, and to perfect his system, President Saied suggests the introduction of a "recall" procedure, allowing voters to remove an elected official that has lost their trust.

These are the broad outlines of the President's vision for a new political regime, which he considers, as articulated in the presidential decree, a "true democratic regime in which the people are the true holders of sovereignty and the source of power and exercise it through elected representatives or through referendum".

Charting a way forward

What can we do now to return to the inner solar system and avoid drifting away from our star into the chaos and violence of the cosmos? Since the President has concentrated most of the powers in his hands, it is now up to him to guide the country back to constitutional order.

The choice of a new Head of Government and the appointment of a government composed of one-third women (including the head of government), reassures us of the President's position on women's rights and gains. It is a good start but not enough to ease fears. It will be necessary for the President to, as soon as possible, give a clear outline of the reforms he intends to undertake to the political system and the electoral law. It will also be necessary to set a date for legislative elections. It is this measure that will allow us to judge the sincerity of the President in his commitment to constitutionalism and parliamentary democracy. Representative democracy is certainly not an ideal system, but it is the system most capable of instilling the democratic separation of powers and avoiding the abuse of people’s rights and freedoms.

A reform decided unilaterally in its substance and process will only fuel tension and fracture the country, thus undermining the chances of a successful return to constitutional order.

For these constitutional and legislative reforms, the President must understand that it is of utmost importance to adopt a participatory approach. A reform decided unilaterally in its substance and process will only fuel tension and fracture the country, thus undermining the chances of a successful return to constitutional order. In this regard, the commission foreseen in the presidential decree, that will assist the President in drafting constitutional revisions, will have to adopt a participatory approach both in the choice of its members and during the proposal drafting process.

The President’s declared intent to initiate a sincere and fair dialogue with young people from all regions on the political and electoral system is interesting in principle, but risks being a pretext for excluding certain political and civil forces in the country. Indeed, the President intends to exclude from the dialogue those who have “stolen the people's money and betrayed the country”, raising doubts about the inclusivity and legitimacy of this dialogue. Moreover, the President does not specify a deadline for this dialogue, let alone the entire process of revising the Constitution and returning to a normal constitutional order.

While waiting for these reforms, it is also of the utmost importance that the President gives solid and genuine guarantees as to the protection of the constitutional rights of Tunisians, and especially the freedom of the press and expression, the right to demonstrate, the right to physical integrity, and the right to a fair trial. Criticism from civil society should not be considered as acts of treason but rather as the ultimate guarantee against arbitrariness. To President Kais Saied, passionate and knowledgeable of the Arab-Muslim heritage, we recall what the Caliph Omar Ibn Al Khattab said: "Blessed be he who points out my wrongs"!

Nidhal Mekki is a researcher at the Faculty of Legal, Political and Social Sciences of Tunis.