Djibouti's new constitution: between longevity in power and the beginnings of socio-political instability

In October 2025, Djibouti adopted a partial constitutional revision that removed the presidential age limit, tightened eligibility requirements, and weakened the role of popular referendums. Adopted amid a tightly controlled political environment, the reform cleared the way for President Ismail Omar Guelleh—in power since 1999—to seek a sixth term in 2026. Roukiya Osman analyses the political and constitutional dynamics behind this revision and assesses its implications for democratic governance and socio-political stability in the country.

[Version originale en français disponible ici]

On 26 October 2025, the Djiboutian parliament adopted a partial revision of the Constitution. Among the highlights are the removal of the age limit for the president, the requirement that all presidential candidates have been continuously resident in the country for at least five years, and the removal of the referendum requirement for the adoption of a new constitution.

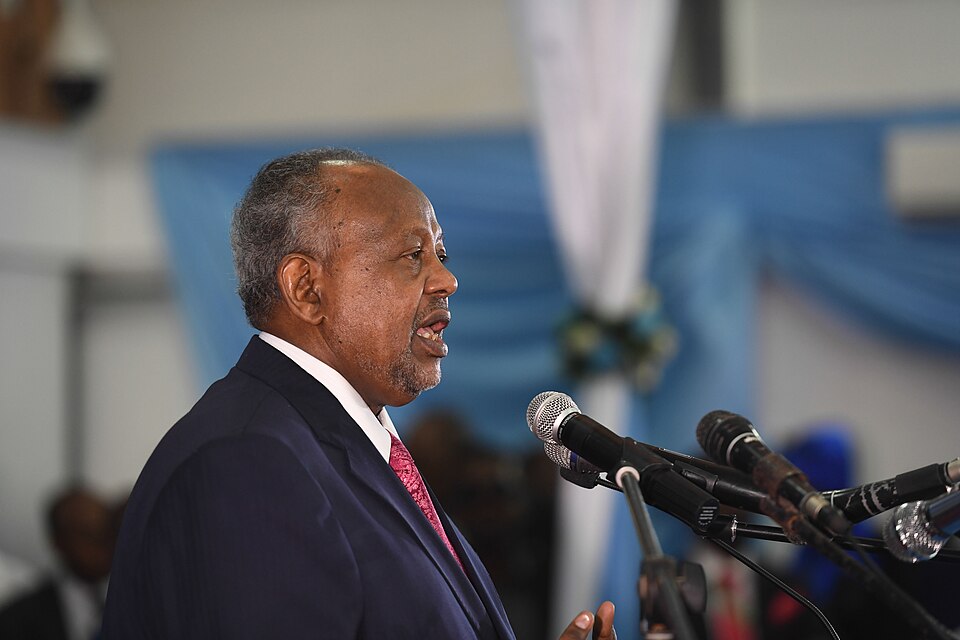

The amendments were approved by the National Assembly on 2 November and promptly promulgated by the President on 6 November. This change comes in a political context in which President Ismail Omar Guelleh, in power since 1999, officially declared himself a candidate for a sixth term in the April 2026 presidential elections at the congress of his party, the Popular Rally for Progress (RPP), on 8 November 2025.

The political and legal context

In 2010, Guelleh amended the Constitution, removing the limit on the number of presidential terms and setting the presidential age limit at 75. Now aged 78, his only option to run for a sixth term was to remove this limit. This proposal was approved by almost all of the 65 members of the National Assembly during the 2 November vote.

This majority is the result of a coalition called the Union for the Presidential Majority (UMP), which includes the Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD), the National Democratic Party (PND), the Social Democratic Party (PSD), and the Union of Reform Supporters (UPR), which won the February 2023 legislative elections despite protests and a boycott by opposition parties. Of the 65 seats in the chamber, 58 are held by the ruling party, compared with seven for the Union for Democracy and Justice (UDJ).

The Djiboutian opposition has often boycotted presidential elections, denouncing the absence of an independent national electoral commission. Although it is struggling to survive, it faces unprecedented difficulties: forced exile, repression, ethno-clan divisions, lack of freedoms, party cloning, and arbitrary dissolutions.

The few remaining dissenting voices belong to the Djiboutian diaspora, which the Minister of Justice described in 2019 as “a new breed of criminals.” The diaspora plays a prominent role on social media, facilitating the dissemination of information hostile to the government. Within the country, the media are under the strict control of Radiodiffusion Télévision de Djibouti (RTD), the national regulatory body that relays the regime's propaganda.

The constitutional revision therefore comes at a time when the country ranks 168th out of 180 in the 2025 press freedom index compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), the opposition is muzzled, independent media are non-existent, and executive and legislative powers are in the hands of one man.

Revisions to the Constitution

Among other amendments—such as the addition of a ban on female genital mutilation (FGM) and any practice that undermines human dignity or integrity, which could have been regulated by a simple organic law, as well as the new Article 65, which subjects the procedures for drafting, voting on, executing, and monitoring the state budget to an organic law—there are some much more controversial changes.

1. A lifetime presidency

Ismail Omar Guelleh, who has been in power for 26 years and is 68 years old, was no longer eligible to run for president under the age limit of at least 40 and no more than 75 on the date of filing for candidacy imposed by Article 23 of the 2010 Constitution—a provision he himself had decided on 15 years earlier.

The new Article 23 removes this restriction by eliminating any age limit for presidential candidates, allowing Guelleh to run for a sixth term and paving the way for him to be re-elected indefinitely. This revision therefore conceals a personal political manoeuvre: the maintenance in power of a president who, in an interview with the BBC in 2022, responded to a journalist who asked him if he would run in 2026: “No, no, no, three times no. You can remember that, I am over the age limit and I have to hand over.”

2. A discriminatory condition designed to exclude the diaspora

The new Article 23 includes another controversial addition, stating that any candidate for the office of President of the Republic must “have resided continuously for at least five years on the date of filing their candidacy, except in the case of a mission carried out on behalf of the State or an international organization.”

It is clear that the introduction of this paragraph reflects the President's desire to further restrict eligibility for the presidency and to limit the possibility of any exiled opposition figures running for office.

It is clear that the introduction of this paragraph reflects the President's desire to further restrict eligibility for the presidency and to limit the possibility of any exiled opposition figures running for office. This discriminatory provision therefore appears to be an attempt at political control and repression deliberately targeting political opponents, whistleblowers, and activists in the diaspora.

3. Removal of the referendum requirement

Given that the amendments adopted in 2025 were made through the constitutional revision process—rather than through the adoption of a new constitutional text by popular referendum—the revision effectively followed the amendment rules set out in the old Constitution. According to its Article 91, which was not amended, the initiative to revise the Constitution belongs jointly to the President of the Republic and the members of Parliament. Any proposed revision must be voted on by a majority of the members of the National Assembly and only becomes final after being approved by referendum. However, the referendum procedure may be avoided by decision of the President of the Republic, in which case the draft or proposed revision must be approved by a two-thirds majority of the members of the National Assembly.

However, the former Article 93 of the 2010 Constitution required that any Constitution be submitted to a referendum in order to be adopted: “This Constitution shall be submitted to a referendum. It shall be registered and published, in French and Arabic, in the Official Journal of the Republic of Djibouti, with the French text being the authentic version.” In the 2025 revision, Article 93 of the Constitution was rewritten to remove the explicit requirement that the Constitution be submitted to a referendum in order to be registered and published; it now only provides that: “This Constitution shall be registered and published in French and Arabic in the Official Journal of the Republic of Djibouti, with the French text being the authentic version.” Similarly, Article 94 was reworded to indicate that entry into force takes place after approval by a qualified majority of two-thirds of the members of the National Assembly rather than after a referendum.

This change therefore appears to be part of a broader strategy of political control over the constitutional process (...).

Because these changes were incorporated through a constitutional revision, they did not have an immediate impact on the validity of the constitution in force, but they do alter the legal framework applicable to the adoption of future constitutional texts. If, in the future, a completely new Constitution were to be drafted, the absence of any mention of mandatory submission to a referendum in Article 93 could therefore mean that this mechanism would no longer be required. This change therefore appears to be part of a broader strategy of political control over the constitutional process, reducing the unpredictable democratic risks associated with a referendum and strengthening the ability of the executive branch and its parliamentary majority to steer sensitive institutional changes.

The winner’s discourse

The ruling coalition defended these changes as an institutional reorganization essential to the stability and continuity of the country, located in a region plagued by wars. It welcomed their adoption, which enjoyed the support of all members of parliament, describing it as an unprecedented political and social consensus. For the government, the partial revision of the Constitution is part of a process of consolidating the rule of law and modernizing institutions.

Reactions from the opposition and civil society

At the national level, the Bloc for National Salvation (BSN), a coalition comprising the Republican Alliance for Development (ARD), the Movement for Democratic Renewal and Development (MRD), and the Movement for Development and Freedom (MoDEL), protested these changes and denounced them as a violation of democratic principles. They are calling for a democratic transition to avoid a new authoritarian drift.

The International Workers and Peoples' Agreement (EIT), of which the MRD party is a member, strongly condemns this unacceptable situation and calls for a return to the constitutional order prior to 26 October and the establishment of an independent electoral commission to ensure that “the 2026 presidential election is finally transparent, free, and fair.”

There is virtually no independent civil society left in the country, and the few voices that identify as such are only present on social media (TikTok and Facebook). The reactions often attributed to civil society regarding this constitutional revision are therefore those of the government. Moreover, Omar Ali Ewado, president of the Djiboutian League for Human Rights (LDDH), has stated that the authorities are preparing “a lifetime presidency for Ismaïl Omar Guelleh.”

Furthermore, there has been no official reaction from the international community or regional organizations. The current chair of the African Union Commission, Mahamoud Ali Youssouf, is a close associate of Guelleh and served as Djibouti's foreign minister for 19 years.

A risk of instability

This constitutional revision impacts the country's socio-political balance and stability. Djibouti is located in the Horn of Africa, a region ravaged by civil wars for several decades. The country is often presented as a haven of peace in a troubled area. This relative stability is based on political manoeuvring between the regime and the country's various tribes and clans. This dangerous game undermines the country's sovereignty and risks fragmenting it into clans like neighbouring Somalia.

The political trajectory as it stands today could therefore create instability if the paths to democratic change and political inclusion remain closed.

By perpetuating himself in power, President Guelleh further weakens this consensus and paves the way for popular uprisings. In Djibouti City, and throughout the country, there is a real sense of abandonment. In the current context, with the President attempting to consolidate his power, the possibility of internal tension is tangible. The political trajectory as it stands today could therefore create instability if the paths to democratic change and political inclusion remain closed.

The interests of foreign powers present in Djibouti could also be threatened in the short or long term. Due to its geostrategic position, located at the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait connecting the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden, Djibouti occupies a privileged position that makes it a key location for global trade. It is in this context that France, the United States, Japan, China, and Italy, among others, have military bases enabling them to intervene in Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

The constitutional amendment lays the groundwork for political uncertainty that could threaten their interests in the short and long term. Concern prevails among diplomatic missions that are closely monitoring the democratic decline. Their interests depend on the socio-political stability of Djibouti. As a result, they are caught between the anvil of a despotic regime and the hammer of a region that is important for global maritime trade.

Conclusion

The constitutional amendments adopted in Djibouti alter the structure of power and favour the longevity of a personalized regime at the expense of peaceful and democratic change. By paving the way for Guelleh to become president for life, they weaken the social fabric and destroy any democratic prospects for the country's future. In anticipation of the next presidential elections in 2026, for which Guelleh has officially announced his candidacy, this situation could lead to socio-political instability and ultimately harm the interests of foreign powers present in the country.

Roukiya Osman holds a PhD in History from the University of Toulouse 2 Jean Jaurès. A specialist in security and peace issues in the Horn of Africa and a former researcher at the Djibouti Center for Studies and Research, she is the author of the book Djibouti, published by De Boeck, and has published several articles, analysis notes, and opinion pieces. She is a member of the Think Tank Thinking Africa network.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Roukiya Osman, ‘Djibouti's new constitution: between longevity in power and the beginnings of socio-political instability’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 16 December 2025, https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/djiboutis-new-constitution-between-longevity-power-and-beginnings-socio-political-instability

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in Djibouti.

If you are interested in contributing a Voices from the Field piece on constitutional change in your country, please contact us at constitutionnet@idea.int.