A Balancing Act: Public Participation, Decision-Making, and Freedom of Speech at the Chilean Constitutional Convention

♦ ♦ ♦ This article is part of a series where experts analyse issues related to the process and substance of Chile's Constitutional Convention. Read more. ♦ ♦ ♦

With its rules of procedure now in place, Chile’s Constitutional Convention is beginning its discussions on the substantive content of the new Constitution. But with nine months remaining (extension included), how will the rules of procedure—particularly those that developed into pivotal discussions during the first stage—influence the substantive constitutional provisions? There are three issues in particular to keep an eye on: the impact of popular participation, how the committees reach agreements, and the safeguarding of freedom of speech – writes Dr. Isabel Aninat

After setting its rules of procedure, the Chilean Constitutional Convention has entered its main phase: the discussion and approval of the substantive issues to be included in the proposal of the new constitution. During the first three months, the Convention´s work was focused in its internal organization, which culminated in the approval of five complementary rules of procedure. On 3 November, the Convention approved its schedule for the upcoming months. As approved, the first voting sessions will occur during the first weeks of February 2022 and the possible deadlock-breaking intermediate referendums—a particularly controversial issue—would take place at the end of May of next year.

What will we witness during the next few months? The Convention has divided its work on thematic committees, following what has been observed in other constituent processes in the region. Seven main thematic committees were created, each one led by two coordinators: (1) system of government; (2) constitutional principles, nationality and citizenship; (3) territorial distribution of power; (4) fundamental rights; (5) environment and economic model; (6) justice system, constitutional organs, and constitutional reform; and (7) knowledge, science and culture. There are also complementary committees: one on the rights of indigenous peoples, one on popular participation, and one on human rights and reparations. Thus, the center of attention will be set on the discussions within each committee and the proposals that each committee will submit to the plenary sessions.

With nine months remaining (extension included), a question to assess in the coming months is how the rules of procedure—particularly those that developed into pivotal discussions during the first stage—will influence the substantive constitutional provisions. There are three issues in particular to keep an eye on: the impact of popular participation, how the committees reach agreements, and the safeguarding of freedom of speech.

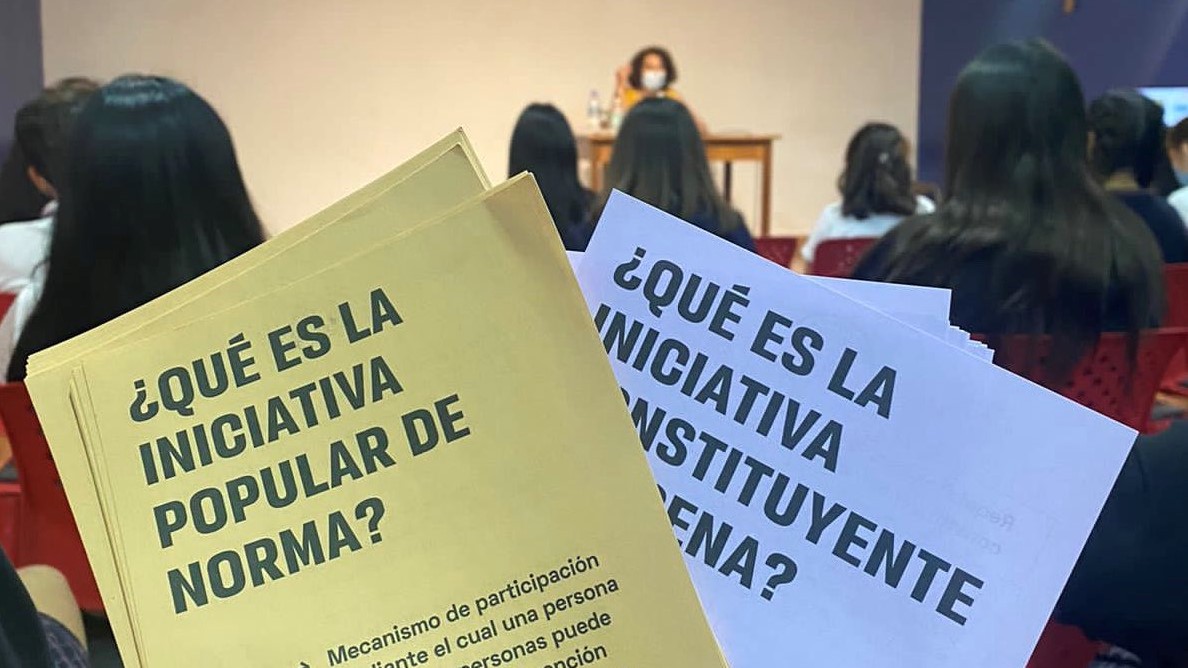

Popular participation in the constitution-making process

Popular participation has been a central issue in the constitutional debate ever since the inauguration of the Convention. Many members of the Convention included participation—in addition to both referendums (entry and exit)—as a main campaign promise. Given the much-vaunted crisis of representation in Chile, popular participation has been regarded as crucial to strengthening the Convention’s (and the whole process’s) legitimacy.

Unsurprisingly, the general rules of procedure include two guiding principles on the issue: a right to “impactful” popular participation—the subject of which can be individuals or groups, from all different sectors, locations, and conducted with cultural and gender sensitivity—and indigenous peoples’ participation, with a specific consultation process. In practice, the general process of public participation has been set in place via several mechanisms including a monthly “territorial week”, for the Convention delegates to engage with the broader public, including indigenous peoples (Art. 73); “popular initiatives”, allowing for civil society, indigenous peoples and young people to present substantive proposals (Art. 81); and the obligation for each committee to establish a period to facilitate public participation (Art. 89). The Convention further set specific rules of procedure for the organization and methodologies for popular participation and constituent education, as well as special rules of procedure for the participation and consultation of indigenous peoples, with special secretariats.

Various declarations in the rules of procedure avow that participation will have a real impact on the debate and approval of the draft constitution. Thus, the rules of procedure contemplate the systematization of the results from the different participation mechanisms—where the participation technical committee will play a crucial role.

As observed over the last weeks, the committees have already enabled various forms of citizen participation in their sessions. In the first weeks, the seven committees received over 4,500 applications for public hearings and some committees have been holding sessions in various cities and locations in Chile. The Committee on Popular Participation has announced the start of the informational and educational period to promote participation, the members of the technical secretariat for popular participation have been appointed, and a digital public participation platform has been launched. Popular initiatives may be presented to the Convention between 8 November and the first week of February 2022. Within just three days of the digital platform’s launch, the Convention received nearly 200 submissions. The submissions will be evaluated for eligibility by the Committee on Popular Participation and will then be published on the public participation platform. Popular initiatives with over 15,000 signatures, from at least four different regions within the country, must be treated as equivalent to the proposals that the Convention delegates present, and, thus, must be discussed and voted on in the same manner (Art. 35).

With the high expectations set regarding popular participation, the main challenge will be to show that people’s inputs have an impact on the Convention’s substantive debate.

With the high expectations set regarding popular participation, the main challenge will be to show that people’s inputs have an impact on the Convention’s substantive debate. Beyond the various formal rules set in place, the impact of popular participation in the constitutional debate will be measured not only by the number of public hearings or initiatives presented, but also how each committee considers or incorporates the proposals. This will entail addressing proposals which will likely be contradictory, biased, too broad or otherwise unsuitable for a constitutional text. And this must be done in a very limited amount of time. The role of the secretariat in systematizing the proposals for the Convention´s discussion will be crucial. But, in any case, how to promote participation while managing expectations will be a key challenge for the next few months to avoid frustration with the Convention.

In addition, the result of popular participation during the next months will almost certainly have an important impact on the substantive content of the new constitution. Several Convention delegates have advanced the idea of including various public participation and direct democracy mechanisms in the future constitutional text. How popular participation functions during the Convention—in its procedure and in its impact—will serve as the test for such rules. It will also encourage the more profound debate of its place in a representative democracy and, in particular, its relation to the role that political parties should play.

Reaching agreements within committees

Since the Agreement for Social Peace and a New Constitution was signed on 15 November 2019, a central issue has been the two-thirds quorum required for approving constitutional provisions within the Convention. An important part of the debate on the general rules of procedure centered on the quorum for different types of voting during the Convention. While the two-thirds requirement is set for the approval of the proposals in the plenary session (Art. 96), within each committee the quorum required is a simple majority (Art 92). Thus, it will be easier for the committees to reach an agreement on each issue before submitting the proposal to the plenary session, allowing the committees to move swiftly in addressing the various topics that each must cover. In a fragmented Convention—as the Chilean Constitutional Convention is—facilitating agreements is a relevant challenge.

However, it will be interesting to observe how the functioning of each committee will impact the voting sessions starting in February. Taking Committee Nº 1 as an example, a decision as fundamental as the next system of government in Chile—whether to maintain a presidential system or switch to a parliamentary government—could be reached by a majority of only 13 out of its 25 members. Undoubtedly, the success of the negotiations and consensus building to meet these voting requirements within each committee will bear on not only the plenary´s discussion but also the possibility of reaching the two-thirds threshold overall. This is particularly important for the most consequential issues in the draft of the new constitution, as the example on the system of government illustrates.

As observed in other constitutional processes, various mechanisms have been implemented to promote broad consensus and facilitate negotiation. One such mechanism for facilitating agreements and avoiding deadlocks is the incorporation of drafting techniques that allow for constructive ambiguity. So far, the Chilean Constitutional Convention has strongly favored the inclusion of extensive and numerous guiding principles—the general rules of procedure establish by itself 27 principles (Art. 3). Will this same tendency of including extensive lists of principles persist in the final text? Will the work within each committee be influenced by the same trend? Will they incorporate the principles already included? While principles may be useful for reaching broader agreements—particularly when the details of justiciable provisions are hard to agree on—they might become problematic when regulating specific institutions that need to function efficiently and coherently.

Will freedom of speech be limited?

Another aspect to keep an eye on will be freedom of speech: Will its regulation in the rules of procedure hamper decision-making within the committees? If so, how will this impact its future substantive regulation?

During the first three months of the Convention, freedom of speech gained central importance. The rules of procedure on ethics include two provisions that generated much controversy. First, the rules include an anti-denial provision, under a definition of historical denialism (“negacionsimo”). This prohibition (Art. 23) extends to all actions or omissions that justify, deny or minimize, defend or glorify human rights violations, atrocities and cultural genocide that occurred between 1973 and 1990 or during the social outburst of October 2019, and those violations suffered by indigenous peoples and tribal groups during the history of Chile since the Spanish conquest. The second provision entails a prohibition on misinformation, a provision that extends to any assertion communicated via analog or digital mediums that presents a fact as real but which the speaker knows or should know is false (Art. 24).

Two rules undercut freedom of speech during the Convention’s discussions and negotiations, as they are framed in very broad and general terms.

Both provisions undercut freedom of speech, as they are framed in very broad and general terms. In addition, and unlike other constituent processes, the current Chilean process is being held under a general context of increasing influence of social media platforms. The impact that social media is having on the constitutional debate is particularly important for the Convention itself and it is likely to shape future discussion on the regulation of various platforms, an issue that transcends Chilean borders. However, how the rules of procedure of the Convention will impact the substantive debates is yet to be seen.

The compliance with both provisions and the role of the Ethics Committee in establishing sanctions for potential infringements in the coming months will give way to a strong debate on freedom of speech. This Ethics Committee is composed of five external members, following gender, decentralization and indigenous peoples criteria and professional requirements, and must follow a specific procedure for assessing complaints. Potential sanctions include reprimand and censorship, economic fines, as well as alternative measures such as public apologies (Art. 42-46).

Even within the Convention, freedom of speech should be the general rule. Limits should be understood in tight and precise terms. The Convention’s proposal for the new constitution should include an understanding of this fundamental right under a provision that promotes rational debate, one that allows for a candid exchange and persuasion based on ideas, widely open to different criticisms and proposals, and one that is conceived under a strong commitment to pluralism and democratic deliberation.

Conclusion

The upcoming months will constitute the heart of the Chilean constituent process: the debate and voting on substantive proposals. Undoubtedly, it will be influenced by the recent results of the November general elections and the upcoming presidential vote. But, it will also be heavily influenced by the rules of procedure that the Convention has given itself. The specific contents of the new constitution are still open, and there is much to watch for in the upcoming months.

Isabel Aninat is the Dean of Universidad Adolfo Ibañez Law School.

Comments

Post new comment