Third Time’s a Charm? Chile Embarks on a New Constitution-making Process

♦ ♦ ♦ This article is part of a series where experts provide insights into Chile's constitution-making process. Read more. ♦ ♦ ♦

A key feature of Chile’s new constitution-making process is the establishment of three separate bodies: an expert commission to draft the constitutional text, an elected council to finalize it, and a technical advisory committee to ensure the draft’s compliance with previously agreed fundamental principles. The move from a fully elected constituent body (as in the last process) to a mix of political appointments and directly elected delegates is an attempt to balance expertise with democratic legitimacy in the hopes of producing a new constitution that will satisfy voters. Nevertheless, significant omissions in the design of the process will need to be ironed out – write Gonzalo García Pino, Miriam Henríquez Viñas and Sebastián Salazar Pizarro

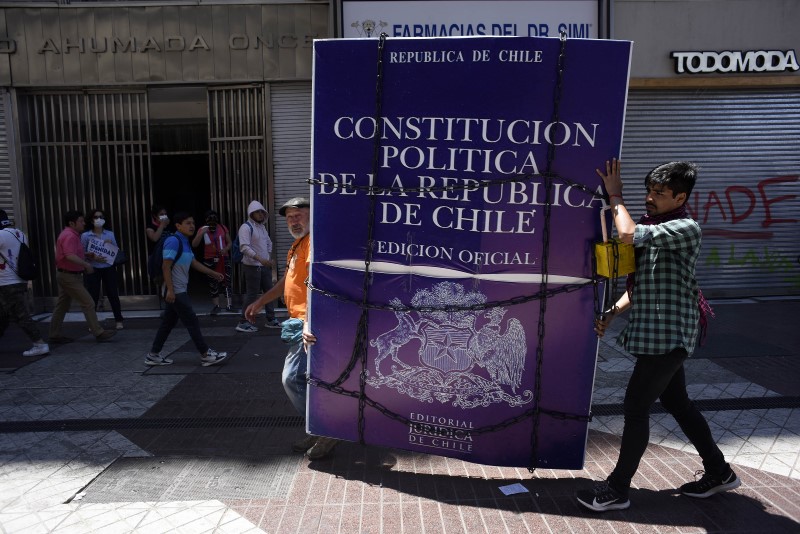

On 11 January 2023, Chile’s Congress passed a bill to start a new constitution-making process after the sound rejection of the draft text that was created by the 2021-2022 Constitutional Convention (previously analyzed in a ConstitutionNet series). The rejection came on 4 September 2022, when Chileans voted in a mandatory referendum. It was the largest vote in the electoral history of Chile, in which more than 13 million people participated. The result was a categorical triumph for the "reject" option, which obtained 61.89% of the valid votes cast compared to 38.11% for the "approve" option. This milestone was a setback for President Gabriel Boric’s government: a confirmation of the failure of the work of the Constitutional Convention and the shift in political momentum toward congressional control of the new process, composed mostly of conservative forces.

In December 2022, 100 days after the referendum and after complex and winding negotiations, political parties represented in Congress signed the "Agreement for Chile", which, especially once converted into a constitutional amendment, detailed the roadmap for a new constituent process. The approved amendment is important because it details the new procedure for the constitution-making process and extracts some lessons learned from the previous process. So, as Chile faces another constituent process — the third attempt if we include the constitutional reforms and draft constitution promoted by former President Michelle Bachelet — this piece highlights the main characteristics of the new process, considers technical issues that must be resolved, and flags some upcoming challenges.

The three bodies of the new process: between expertise and legitimacy

The main feature of the new constituent process is the establishment of three different bodies, with differentiated mandates and compositions, as opposed to the single Constitutional Convention, established as part of the past process. This time, the Constitutional Council will be a directly elected body whose sole purpose is to discuss and approve a preliminary draft of the new constitution. The Constitutional Council will be composed of 50 delegates directly elected in accordance with the system for the senate elections, with open lists that may include independents. There will also be an “Expert Commission”, a body made up of 24 experts (12 appointed by each house of Congress) with outstanding professional and/or academic careers. The Expert Commission’s most significant function will be to propose to the Constitutional Council a preliminary draft of a new constitution. Finally, there will be a Technical Admissibility Committee, composed of 14 jurists, also with outstanding professional and/or academic careers, named by the Senate but appointed by the Chamber of Deputies. The Technical Admissibility Committee will determine whether any proposed constitutional provision contravenes the previously agreed “bases institucionales”: 12 foundational guiding principles included in the “Agreement for Chile”. According to the Agreement, none of the proposed provisions may contravene these principles, nor may these contents be absent in the draft to be issued by the Constitutional Council. Examples of such preconfigured content are Chile’s commitment to social and democratic rule of law, to being a unitary and decentralized state, to bicameralism, to protecting fundamental human rights and freedoms, and to conserving nature and biodiversity. A political compromise is shown in these principles, which constrain the future content of a new constitution. For example, the principles safeguard private property (which could be interpreted as protecting private water rights) and prevent the elimination of the Senate, two major and controversial issues in the last process. Nevertheless, the guiding principles are broad and open to interpretation, which heightens the likelihood that the Technical Admissibility Committee may play an important role.

Consolidation of the parity principle but potential lack of Indigenous representation

After the 4 September referendum, several political actors anticipated early on that, if there was to be a new constitution-making process, it should ensure that the constituent bodies would incorporate parity. This announcement was honored in the political agreement and enshrined in the constitutional reform that established the new process. In the previous process, Chileans chose via referendum that the Constitutional Convention should be fully elected and composed of a balanced number of men and women. In fact, the Convention was made up of 78 male and 77 female delegates, making it the first-ever constitution-making body with gender parity. To achieve this result, a formula was designed and applied at two moments: firstly prior to the election, with parity required in the nominations, and secondly after the election, which required parity in the allocation of seats.

A similar formula – although with modifications – was approved for the election of the Constitutional Council. Thus, parity in the candidacies means election lists must indicate the order of precedence of the candidates in the ballot for each senatorial district, starting with a woman and alternating with a man. A complex procedure would ensure parity in the Constitutional Council even if the outcome of the elections would result in overrepresentation of one sex. The importance of gender parity is recognized not only in the directly elected bodies, but also in the technical bodies, whose members are appointed.

The lack of guaranteed representation of Indigenous peoples in the Constitutional Council creates a key question about the inclusivity of this process.

In the previous process, 17 seats were reserved for Indigenous peoples in the Constitutional Convention, while in this process supernumerary seats for Indigenous peoples will be assigned in the Constitutional Council depending on the percentage of votes cast for a separate list of Indigenous representatives at the national level compared to the total number of votes in the non-Indigenous constituencies. While a culture of gender parity is gradually being consolidated in Chile’s democracy, the lack of quotas for Indigenous peoples in the Constitutional Council, and no guaranteed representation in the other bodies, creates a key question about the inclusivity of this process.

Stages (and omissions) of the new process

The schedule of this new process contemplates a series of stages, which will culminate in December 2023. On 6 March, the Expert Commission and the Technical Admissibility Committee will be installed, with the first one having three months to prepare a preliminary draft of the new constitutional text. On 7 May, the elections will be held for the members of the Constitutional Council, which will be installed in June with five months to complete its task of finalizing the constitutional text. The text will then be submitted to a ratifying referendum on 17 December 2023. It will be mandatory to vote in both the Constitutional Council elections and ratifying referendum.

However, the plans do not address several relevant issues. Some of the omissions are probably deliberate and others are perhaps simple oversights whose magnitude could generate difficulties in the future. For example, although deadlines are established in the discussion of the constitutional reform, there is no provision – as there was in the past – for an extension of the deadlines. It indicates that political will favors a shorter process, but not foreseeing a possible extension leaves no alternatives if the allotted time is insufficient and the objectives cannot be fulfilled.

What happens if the proposed constitution is rejected in the exit referendum?

Other omissions are more complex: What happens if the Constitutional Council does not approve the preliminary draft of the Expert Commission within the established term (article 152)? Can the Expert Commission propose transitional rules in the preliminary draft? Article 157 only provides the Constitutional Council with the power to establish transitory articles concerning the entry into force of the provisions or chapters of the new constitution. By whom and with what resources will the new constitutional text be made known to the citizens so that they may be informed voters in the ratifying referendum? The constitutionalized plan only contemplates televised programming on free-to-air television channels. Will the commissioners of the Expert Commission and the members of the Technical Admissibility Committee keep their regular jobs during the process? And, fundamentally, what happens if the proposed constitution is rejected in the exit referendum?

Upcoming challenges

A number of challenges stand out when looking at the design of the process, including those related to technical advice, public participation, and the functioning of the bodies. First, the process should have technical advice and financial and administrative support in all its stages, which are essential for the proper establishment and operation of the bodies. Both issues were not sufficiently addressed in the previous process, especially at the beginning. Now, the Congressional Library will provide technical support and archiving. The bodies may also request specialist information from universities to illuminate some aspects of the constitutional debate.

The election of delegates makes the process representative, but the current standards of constitution-making processes demand sufficient and timely public participation…

Second, and indispensable to give legitimacy to the project of the new constitution, public participation is key. The election of delegates makes the process representative, but the current standards of constitution-making processes are more rigorous and demand sufficient and timely public participation as a basic element. The approved design on this point is precarious: it only contemplates that public participation is established by the bodies’ Rules of Procedure, in the stage of the Constitutional Council’s operation, and with two universities to coordinate it. At least, according to what was approved, citizens’ initiatives allowing the public to present proposals should be allowed.

A coherent operation between the Expert Committee and the Constitutional Council is necessary in practice, giving more prominence to the latter, considering what is prescribed by the bodies’ Rules of Procedure. According to the constitutionalized plan, the Expert Commission will delimit the scope of the Constitutional Council's decisions and not the other way around. The Constitutional Council appears to be more akin to a parliamentary chamber that ratifies the proposals of the Expert Commission. For example, the Constitutional Council can only approve, approve with modifications, or incorporate new provisions in the preliminary draft submitted by the Expert Commission, but cannot eliminate them (Article 71). On the other hand, the report formulated by the Expert Commission to improve the text proposed by the Constitutional Council shall be deemed approved by the latter with a quorum of three-fifths of its members in office (Article 79) and rejected with a quorum of two-thirds (Article 84(4)). As can be seen, the Constitutional Council has fewer requirements for approving the proposals of the Expert Commission and more restrictions for rejecting them.

Two essential milestones of this process have already been reached: the approval of the bodies’ Rules of Procedure and the election of the experts who will make up the Expert Commission and the Technical Admissibility Committee. It has been argued that this constituent process would be founded on uncertainty and fear in the face of the rise of populism that is emerging around the world, so the first great challenge will be for the experts who were appointed by the Congress to reduce this distrust and seek cross-cutting agreements directly beneficial to the country, allowing the proper conduct of this process, which attempts to balance expertise with democratic legitimacy in the hopes of finally producing a new constitution that will satisfy voters.

Gonzalo García Pino is a professor of Constitutional Law and Political and Constitutional Theory at the Law School of the Alberto Hurtado University. Miriam Henríquez Viñas is Dean of the Faculty of Law and professor of Constitutional Law and Political and Constitutional Theory at the Alberto Hurtado University. Both are directors of the Constitutional Nucleus, an initiative of the Law Faculty of the Alberto Hurtado University to contribute to deliberation and informed participation on the current constitutional process. Sebastián Salazar Pizarro is a professor of Constitutional Law and Political and Constitutional Theory at the Law School of the Alberto Hurtado University. He is also academic coordinator of the Constitutional Nucleus.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Gonzalo García Pino, Miriam Henríquez Viñas, and Sebastián Salazar Pizarro, ‘Third Time’s a Charm? Chile Embarks on a New Constitution-making Process’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 3 January 2023, https://constitutionnet.org/news/third-times-charm-chile-embarks-new-constitution-making-process

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in Chile.