Indonesia’s stringent presidential nomination requirements: Constitutional Court upholds parliamentary threshold

Indonesia has one of the strictest presidential nomination requirements in the world. While the Constitutional Court has upheld the requirements, an earlier decision that presidential and legislative elections must be held simultaneously has complicated their application. Regardless of the judicial outcomes, the debates on parliamentary threshold requirements are likely to continue in the leadup to future presidential elections – writes Professor Butt.

Introduction

On 25 October 2018, the Indonesian Constitutional Court upheld the constitutionality of the requirement, imposed for the 2019 presidential elections, that aspiring presidential candidates must be nominated by political parties or coalitions who won at least 20% of seats or 25% of the vote in the 2014 legislative elections Notably, this requirement is imposed through legislation, rather than in the constitution, which has paved the way for these court challenges. The retention of the requirement means that Indonesia has one of the most stringent presidential nomination requirements worldwide.

Since its establishment in 2003, Indonesia’s Constitutional Court has heard many challenges from would-be presidential and vice-presidential candidates who have been precluded from standing for election. They have complained about restrictions that favour Indonesia’s larger parties and the candidates those parties nominate. These restrictions, in effect, close off opportunities for smaller and emerging parties to put forward presidential candidates, and even entrench the influence of large parties in subsequent parliamentary terms.

One of these legislative restrictions, found in provisions of Indonesia’s electoral statutes, is that candidates can only stand for election as president or vice president if they are nominated by a party or coalition that meets the so-called ‘presidential nomination threshold’ (ambang batas pencalonan presiden) - that is, the party or coalition obtains a minimum number of parliamentary seats or votes in general elections. For the 2004 elections, this threshold was 15% of seats or 20% of the popular vote; but prior to the 2009 elections, the larger parties in the legislature voted to increase it to 20% of seats or 25% of the vote, hoping that this would guarantee that only their own nominees would be able to stand. This strategy has met some success. Only three candidate pairs contested the 2009 elections and two in 2014; and only two will compete in the upcoming 2019 presidential elections.

Indonesia’s national legislature is notoriously fragmented, with several parties holding seats, but few having ever held more than 20% of seats.

The October decision of the Constitutional Court is the most recent on this threshold. The Court upheld the constitutionality of the 20/25% threshold, retained in the 2017 General Elections Law, rejecting calls for it to reduce the threshold to zero, or to remove the party nomination requirement altogether. This decision maintains the Court’s view, expressed in at least eight decisions issued since 2008, that the Constitution gives the national parliament latitude to impose the threshold, and that the threshold meets two important policy objectives: to ensure that the president and vice president ultimately elected have broad support in the legislature, and to encourage parties to work together, thereby ‘simplifying the party system’. These objectives are deemed particularly important given that, since democratisation from 1998, many new parties have emerged, leaving Indonesia’s parliament highly fragmented, despite efforts in the past decade or so to weed out some of the smaller parties by imposing minimum parliamentary representation requirements. In the absence of a high presidential nomination threshold, there is fear that political fragmentation may lead to the proliferation of presidential candidates.

The October decision, while not particularly significant in the development of the constitutional and legislative framework for the nomination requirement and the threshold, has once again drawn attention to them. This brief article discusses this framework, particularly in view of a 2013 Constitutional Court ruling that required that presidential and general legislative elections be held simultaneously.

Presidential elections in Indonesia

For 32 years (1966-1998), former President Soeharto maintained authoritarian rule under the so-called ‘1945 Constitution’ - which was the constitution Indonesia promulgated the day after it declared its independence on 17 August 1945. Under that Constitution, the President was appointed by the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) the composition of which Soeharto controlled, guaranteeing his re-election every five years. This practice was largely retained in the immediate post-Soeharto era, with the main difference in its operation being that most MPR members were democratically elected, so the MPR’s choices were genuine, not just a rubber stamp, as had been the case under Soeharto.

The threshold is designed to address concerns regarding parliamentary fragmentation and the proliferation of presidential candidates.

However, this practice was called into question in 1999, when the MPR chose Abdurrahman Wahid as a ‘compromise’ president, even though Partai Demokrasi Indonesia - Perjuangan (PDI-P) - the electoral vehicle for Megawati Soekarnoputri - won far more votes than his party in the 1999 elections. Consequently, Wahid’s presidency lacked legitimacy and eventually collapsed amid allegations of incompetence and corruption, and after a long struggle to impeach him during which he called on the military to help him disband parliament. This controversy inspired the MPR to amend the Constitution to require that the president and vice-president be directly elected, as a pair. Political parties and coalitions must now propose their presidential and vice-presidential candidates prior to a general election (see article 6A(2)). Article 6A(3) also requires that candidates must, in addition to a countywide majority, win more than 50 percent of the vote across more than half of Indonesia’s provinces; and, that if these requirements are not met, then the two pairs receiving the most votes compete in a run-off (Article 6A(4)). The Constitution also authorises the national legislature to enact statutes containing ‘procedures for the implementation of presidential elections’ (article 6A(5)). Article 6 of the Constitution contains some of the requirements that presidential candidates must meet in order to stand.

Indonesia’s first direct presidential election was successfully held in 2004 and there have been two more since then, in 2009 and 2014. All of them took place three months after general legislative elections. As mentioned, Indonesia’s national legislature is notoriously fragmented, with several parties holding seats, but few having ever held more than 20% of seats. This three-month gap has long been considered necessary because it gives parties time to cobble together coalitions to meet the threshold to nominate their preferred presidential candidates.

The Constitutional Court in 2013 ruled that presidential and parliamentary elections should held on the same day, invalidating the legislative provision that provided for the three-month gap.

In 2019, general legislative and direct presidential elections will take place on the same day. This is because of a decision, issued by the Constitutional Court in 2013, invalidating the legislative provision that provided for this three-month gap. The Court took the view that having two separate elections was inefficient and had undesirable consequences - including that it forced presidential and vice-presidential candidates to engage in political bargaining that could undermine the process of governing in the future. As discussed below, this 2013 decision raised practical questions about how the threshold should operate.

Presidential threshold cases

As mentioned, the Court has heard numerous cases challenging the constitutionality of the presidential threshold. The Court gave its first full consideration of the issue in a 2008 case brought by a group of applicants, including several smaller political parties. They put forward various constitutional arguments. One was that the threshold impeded their constitutional right to stand for president or vice-president, if they could not obtain the requisite support. Another was that the threshold was discriminatory and caused injustice, if a candidate had insufficient party support. Yet another was that the threshold was unconstitutional because the Constitution required party nomination but imposed no threshold. Applicants also claimed that the threshold was undemocratic, because it prevented elected representatives whose parties or coalitions did not meet the threshold from nominating presidential candidates.

The Court has invalidated a statutory provision regarding the time of elections (a procedural choice) while upholding the threshold (a substantive choice).

A six-judge majority rejected these arguments. The Court ruled that the threshold was not discriminatory or unjust, because it applied equally to all presidential candidates. The threshold also did not violate the right to stand. On the contrary, it entitled candidates to be nominated by parties or coalitions that had been elected by the people and met the threshold. Also, just because the Constitution did not mention a threshold did not mean that the threshold was unconstitutional. Rather, it was simply an ‘extension’ or ‘elaboration’ (penjabaran) of the constitutional provisions about presidential nomination. As for the anti-democratic claim, the Court decided that whether a party meets the threshold is determined by voters. Indeed, nomination was merely an indication of initial support: whether candidates in fact enjoyed sufficient public support to become president or vice-president was determined in the presidential election.

Three judges dissented. They argued that the relevant constitutional provisions were already clear and required no elaboration. For them, adding the threshold requirement was entirely political. They also opined that the constitution gave parliament the authority to enact implementing legislation on election procedures, but that imposing the threshold went beyond this to tamper with candidacy prerequisites, which were already covered in Article 6 of the Constitution.

Which parliament?

The presidential threshold was a matter of significant debate when the national parliament deliberated a new election law in 2017. But the threshold was retained in the statute ultimately enacted in mid-2017, even though many of the smaller parties disapproved and staged a walk out during discussions. One sticking point, which emanated from the decision of the Constitutional Court that legislative and presidential elections should be held on the same date, was whether the threshold should be based on the number of seats or votes obtained at the legislative election held on the same day as the presidential election, or whether the results in the previous legislative election should be used. After much debate, it was decided that the results of the 2014 election should determine the nomination of candidates for the 2019 presidential elections. This approach was adopted despite concerns being raised about its legitimacy, not least because a party that polled well in 2014 might fare badly in 2019 because of poor performance, yet still have a say in who can be nominated for president for the 2019-2024 term.

The decision of the Court may lead to cumbersome coalitions, whose members disagree on fundamental issues, potentially undermining one of the policy justifications for the threshold.

Yet there seemed to be no alternative, at least if legislative and presidential elections were to be held simultaneously, following the Court’s 2013 decision. This is because parties would need to enter into coalitions to nominate pairs before they knew how many votes they would have, leaving them unsure about who to join with or even how many coalition partners they needed to attract to meet the threshold. One result could be that parties would ‘over-coalesce’ – that is, form a coalition that obtains far more votes than they ultimately needed to meet the threshold – to ensure that they can nominate a candidate that will protect at least some of their interests. This could result in cumbersome coalitions, whose members disagreed on fundamental issues. If this occurred, the internal politicking and fragmentation that already characterises Indonesia’s parliamentary practices could worsen, further hampering the national legislature’s ability to effectively perform its functions, including lawmaking. Another result could be to push out smaller parties. The number of votes they would obtain could be difficult to predict, making them less attractive as coalition partners and ultimately excluding them from nominating any candidates.

The October 2018 presidential threshold decision

Several constitutional challenges have been launched against the threshold restated in the 2017 statute. However, the Constitutional Court, as before, refused to invalidate the threshold, pointing to its reasoning in cases about the threshold over the past decade mentioned above, which has emphasised the need for support for the president in the legislature and the need to encourage parties to work together.

Even if the Court had decided to overturn its previous decisions and invalidate the threshold, the decision would almost certainly not have been enforced for the April 2019 elections.

A January 2018 decision about the threshold deserves special note, however. The majority refused to overturn its previous line of cases, but a two-judge minority dissented, putting forward some new arguments. Justices Saldi Isra and Suhartoyo held that a general policy to provide legislative support for the president and to simplify the party system impeded the exercise of various democracy-related rights, including the right to stand for election. Policy could not override constitutional rights, they said. They also observed that the threshold undermined the separation between the legislature and the executive, because it gave the legislature too much power to determine presidential nominations. Critically, too, they objected to the national parliament giving itself power to both set nomination thresholds and nominate candidates for the 2019 presidential elections. Indeed, this would hardly support government stability if the makeup of parliament shifts significantly after the 2019 elections. They would have removed the threshold requirements.

Conclusion

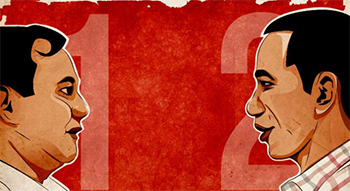

The significance of the October 2018 decision is relatively low. A majority of the Court maintained its stance from earlier cases, and the same two minority judges pointed to their decision in the January 2018 case. In any event, parties in the legislature had already coalesced to nominate their presidential candidates in August 2018. Two pairs will stand for election: the current President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and his vice-presidential running mate Ma’ruf Amin (a conservative Islamic leader); and General Prabowo Subianto (who unsuccessfully competed against Jokowi in the 2014 presidential elections) and current Jakarta Deputy Governor Sandiaga Uno. Even if the Court had decided to overturn its previous decisions and invalidate the threshold, the decision would almost certainly not have been enforced for the April 2019 elections. Undoubtedly, however, the presidential threshold will, as it always has, remain an issue of significant debate in Indonesia in the leadup to future presidential elections. Indeed, if Prabowo Subianto wins in 2019, he may eliminate the threshold and may even do away with direct presidential elections altogether.

Simon Butt is Professor of Indonesian Law at the University of Sydney Law School. He has written widely on Indonesian law.