The review of constitutionalized ethnic quotas in Burundi: a turning point?

The Burundian Senate has embarked on an assessment of the country’s ethnic quotas as mandated by the 2018 Constitution. These quotas, a pivotal aspect of the power-sharing framework established by the 2000 Arusha Agreement, ensure representation of Hutu and Tutsi in all governmental roles and institutions. Despite fostering multi-ethnic parties, the quotas have not prevented the ruling party from consolidating power. Opinions vary on the continuing necessity of maintaining the quotas, including the prerequisite conditions for their elimination. Nevertheless, if the evaluation is conducted in good faith, this process can offer a platform to reach a shared vision of the future, including by addressing persistent challenges in governance - write Alexandre Wadih Raffoul and Réginas Ndayiragije

♦ ♦ ♦ Lire en français ♦ ♦ ♦

Introduction

On 31 July 2023, the Burundian Senate officially opened an evaluation into the future of ethnic quotas in Burundi, responding to a provision in the 2018 Burundian Constitution that gave the Senate five years to assess whether ethnic quotas in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the state are still relevant (Article 289). This piece provides an overview of the design and practice of ethnic quotas in Burundi since 2005. While the main merit of the quotas system has been to foster the emergence of multi-ethnic parties and a reduction in the salience of ethnicity in politics, this system has not prevented the gradual concentration of power in the hands of the ruling CNDD-FDD party and erosion of the protections that the quotas offered to the Tutsi minority.

“Security for the minority, democracy for the majority”

The previous 2005 Constitution completed, formalised, and ‘sanctified’ the ethnic quotas enshrined in the 2000 Arusha Agreement, a key step to ending the Burundian Civil War. The adoption of this constitution opened a window of opportunity to put an end to decades of inter-ethnic violence that had beset the two main ethnic categories, Hutu and Tutsi, respectively representing 85 per cent and 14 per cent of the population. The resulting constitutionalized ethnic quota system was complex and multi-layered. The government was composed of 60 per cent Hutu and 40 per cent Tutsi, with the president assisted by two vice-presidents coming from different ethnic and party backgrounds. The seats in the lower chamber of the parliament (National Assembly) were distributed following the formula of 60 per cent Hutu, 40 per cent Tutsi, and three Members of Parliament (MPs) from the smaller Twa ethnic category. The proportions were achieved through multi-ethnic closed electoral lists, allowing a maximum of two out of three successive candidates to have the same ethnic background. A mechanism of co-optation by the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) was established to adjust representation in case the electoral results did not align with the quotas, and to appoint the three representatives of the Twa community. The upper chamber of the parliament was composed of 50 per cent Hutu, and 50 per cent Tutsi, with two senators (one Hutu and one Tutsi) being elected by municipal councillors in each province of the country. The design of the electoral system thus forced political parties to present multi-ethnic lists of candidates for both chambers of parliament. Ethnic quotas also extended to the military and police forces (50 per cent Hutu / 50 per cent Tutsi), the local administration (maximum 67 per cent of communal administrators belonging to one ethnic group), and public companies (60 per cent Hutu / 40 per cent Tutsi).

This quota system represented a compromise between the two main factions during the Arusha negotiations and the constitution-making process, which can be summarized by the formula “security for the minority and democracy for the majority.” On the one hand, the G7 group, comprising of parties representing the Hutu demographic majority, demanded a transition to majoritarian democracy after decades of exclusion and Tutsi monopolisation of power. They additionally called for inclusive security institutions to eliminate the risk of Tutsis using their full control of the army as a veto power. This demand was informed by the experience of the military coup by a Tutsi-controlled military faction in 1993, which had put a halt to the democratic process. On the other hand, the G10 coalition, with parties representing the Tutsi minority, demanded guarantees against perpetual exclusion from institutions in the form of ethnic quotas. The ingenious quota system that was finally adopted reconciled these two positions by guaranteeing a minimal representation for Tutsis, while still providing majoritarian democracy for Hutus. The key to this ‘associative’ institutional design is multi-ethnic parties, which can guarantee the representation of minority groups, without segmenting the electorate, nor ethnicizing politics.

The 2005 Constitution provided a blueprint for a remarkably peaceful transition to peace and a decrease in, though not a complete disappearance of, the political salience of ethnicity in the post-war period. After decades of ethnic conflict, the political parties (some with a history of quasi-ethnic homogeneity) presented multi-ethnic lists of candidates in the first post-conflict elections, and continued to do so in the following elections. Explicit ethnic mobilization all but disappeared from campaign rhetoric as politicians stressed (at least in their official communications) the importance of national unity. Even when ethnic tensions and discourses reappeared during the political crisis surrounding Pierre Nkurunziza’s bid for a third presidential mandate in 2015, ethnic discourse failed to resonate amongst the population. A key reason for this resilience is that the main political fault lines are not ethnic anymore but instead based on party affiliation: the two biggest political blocs (the ruling CNDD-FDD party and the main opposition party CNL) are both former Hutu-dominated rebel groups, but there are Hutus and Tutsis in the ranks of both the government and the opposition. While power-sharing is known for its inclination towards ‘the lowest common denominator’ policy-making at best and to immobilism at worst, the Burundian experience tells a markedly different story. Even policies that have an important ethnic salience (e.g., land restitution and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission) did not result in ethnic voting or positioning in the parliament.

The ruling party strategically distributed most influential ministerial positions to Hutu loyalists and increasingly shifted the exercise of power to parallel structures where ethnic quotas did not apply.

However, an overly rosy picture of the situation should not be painted. While the quotas might have turned the ruling CNDD-FDD party into a champion of ethnic diversity (in public), they did not succeed at preventing it from progressively monopolizing power. The party could easily accommodate quotas by co-opting Tutsi candidates, but its internal decision-making structure remained dominated by Hutu wartime generals. The CNDD-FDD strategically distributed most influential ministerial positions to Hutu loyalists and increasingly shifted the exercise of power to parallel structures where ethnic quotas did not apply. The leadership and functioning of the UPRONA – the former flagship party for Tutsi representation – were hijacked by the CNDD-FDD through governmental interference in its internal organisation. As the opposition boycotted elections in response to repression, intimidation, and an uneven playing field as early as 2010, the CNDD-FDD dominance in political institutions grew. As a result, most Tutsis accessing positions of power gradually did so through the CNDD-FDD or its associates (and to a lesser extent through other parties once dominated by Hutus). A controversial decision by the Constitutional Court in 2007 ruled that the seats of parliamentarians expelled from their parties were considered vacant. This created a precedent whereby it became extremely difficult for parliamentarians to oppose party lines to defend their ethnic communities. Hence, the question of meaningful, substantive representation as a consequence of descriptive representation is brought to the forefront.

Quotas evaluation: Threat or opportunity?

The new constitution, adopted by referendum in 2018 under the initiative of then-President Pierre Nkurunziza, introduced notable changes. Most importantly, the new constitution eliminated the requirements for a ‘national unity’ government (former Article 129) and brought about a shift from a presidential to a semi-presidential system. One of the two vice-presidents was replaced by a prime minister, without party or ethnic affiliation restriction. The vice-president (from a different ethnic and party background than the president) was preserved, but the role was reduced to ceremonial functions. Moreover, the 2018 Constitution removed the requirement of having a qualified majority to adopt ordinary laws, which previously provided some veto powers to minority groups. While this constitution opened the possibility for President Nkurunziza to extend his rule with two additional terms, he eventually stepped down in 2020 before his sudden death from a suspected case of Covid-19. The CNDD-FDD candidate, Évariste Ndayishimiye, won the presidential election the same year.

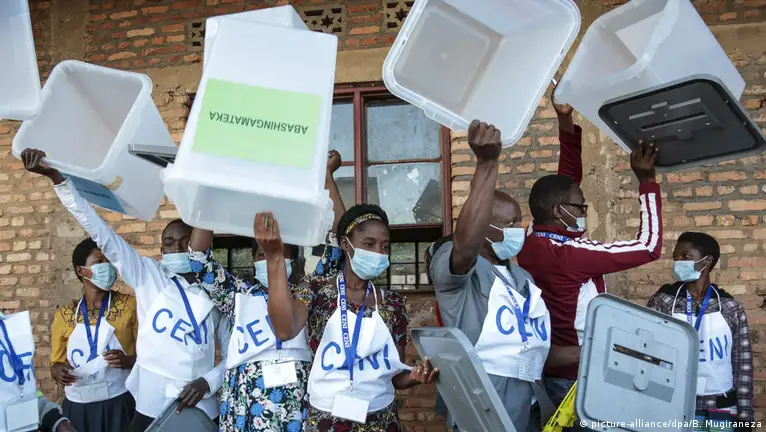

In practice, the quotas evaluation consists of a series of stakeholder consultation meetings organized by the Senate in every province of the country, which will form the basis of a report to be delivered by the Senate to the Government within two years.

Besides the above-mentioned changes, ethnic quotas in the government, legislature, and security forces were otherwise left largely untouched, and have even been extended to the judiciary. However, the new constitution mandated the Senate to evaluate the pertinence of maintaining ethnic quotas, which had always been conceived of as a transitional device. In practice, the evaluation consists of a series of stakeholder consultation meetings organized by the Senate in every province of the country, which will form the basis of a report to be delivered by the Senate to the Government within two years. Somewhat surprisingly, this process does not seem to be backed by an evidence-based study on the impacts (or lack thereof) of the quotas in addressing ethnic imbalances and protection of minorities. While there seems to be room for diversity of opinions during the meetings, the consultative format could raise concerns of a purely cosmetic process. Nevertheless, any eventual elimination of the ethnic quotas would necessitate a revision of the Constitution, which would not be insurmountable given CNDD-FDD’s total dominance of the legislative institutions and the possibility to resort to a referendum. Although the stakes involved are high for Tutsi CNDD-FDD MPs, it is unlikely that they would oppose elimination of the quotas. This is mainly because the voting system in the Burundian parliament lacks anonymity, and being expelled from their party would result in the loss of their seat.

What conditions should be met for eliminating the ethnic quotas? Opinions diverge in the Burundian public debate. One perspective (largely championed by the ruling party CNDD-FDD) asserts that ethnic quotas should be removed since they entrench ethnic divisions and violate the principle of meritocracy. “It is high time”, remarked the president of the Senate recently, “that people be appointed to different functions based on their competences, not their ethnic identity.” Another argument, also often espoused by CNDD-FDD members, is that ethnic quotas represent a form of ‘affirmative action’ to address ethnic imbalances in public institutions, and in particular the historic exclusion of Hutus before 2005. According to this view, quotas should persist only if such inequalities persist, but would become unnecessary if they have disappeared. Finally, another view (mostly from the opposition) considers ethnic quotas as guarantees for the Tutsi minority, addressing the fear that state institutions could be used against them. Since this fear, which results from a violent history, has not disappeared, proponents of this stance advocate for the continued use of quotas.

Conclusion

The consequences of eliminating ethnic quotas are difficult to predict. On one hand, the elimination would largely formalize the existing de facto situation of minimal Tutsi influence on political power. On the other, removal of the quotas could possibly result in the end of multi-ethnic parties in Burundi. Moreover, the symbolic impact of eliminating one of the last components of the Arusha Agreement still standing could spark further anxieties and resentment amongst segments of the Tutsi community.

While ethnic power-sharing has contributed to significantly defusing the political manipulation of ethnicity, this evaluation could also become an opportunity to set new and ambitious goals, restore trust in public institutions, and reinforce national unity. This evaluation could serve to build a common understanding of the existing quota system, including its flaws and limitations. It can also be an opportunity to perfect the system, define measurable indicators of success, and improve the representation of ‘others’, that is, non-dominant groups. If the process is conducted in good faith, the evaluation can offer a platform to discuss issues of misgovernance, including clientelism, nepotism, and state capture – persistent challenges justifying, two decades later, the demand for ethnicity-based representation. To achieve this goal, the evaluation requires a fine-grained methodology, premised on a shared commitment for a transparent, inclusive, and well-intentioned process.

Alexandre Wadih Raffoul is a PhD student at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University, Sweden. His research focuses on ethnic conflict, power-sharing, and peace negotiations.

Réginas Ndayiragije is a PhD student at the Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp, Belgium. His research interests are power-sharing, peacebuilding, and transitional justice.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Alexandre Wadih Raffoul and Réginas Ndayiragije, ‘The review of constitutionalized ethnic quotas in Burundi: a turning point?', ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 4 September 2023, https://constitutionnet.org/news/review-constitutionalized-ethnic-quotas-burundi-turning-point

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in Burundi.

Comments

Post new comment