Cameroon’s political crisis: Why a onetime peace haven might be headed for the unknown

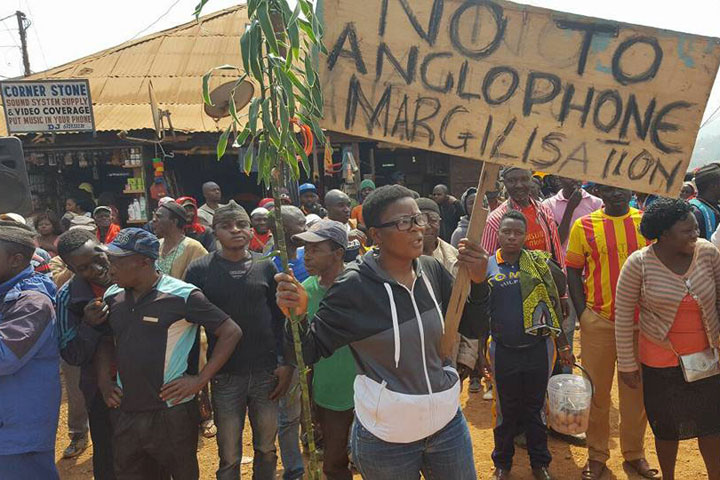

A sense of marginalization accentuated by inadequate corrective measures, but often also violent government crackdown, has triggered popular protests in Cameroon’s two English-speaking regions. Activists and international actors have demanded open and inclusive political dialogue, which may result in significant legislative and constitutional reform, the lack of which will vitalize demands for independence in these regions. Presidential elections in 2018 offer significant prospects for a pathway out, especially if the elections result in regime change. But the lack of clarity regarding incumbent President Biya’s intentions creates an uncertain future – writes Yuhniwo Ngenge.

On 31 October 2017, the UNHRC announced that 5 000 Anglophone Cameroonians fleeing violent political conflict in the English speaking part of the country had crossed into Nigeria, and that it was expecting to receive another 40 000 should the conflict continue. A civil disobedience campaign, which started in late 2016 following inadequate—and often violent—responses by authorities to demands from Anglophone lawyers and teachers for sectoral reforms, quickly morphed into pressure for the government to address the so-called Anglophone Problem. Dismissed and trivialized by Cameroon’s French-speaking majority as a non-issue until now, it refers to decades of perceived assimilationist and discriminatory politics by an entrenched and historically dominant francophone government. This has left English-speaking Cameroonians, who constitute about 22% of Cameroon’s estimated 24 million inhabitants, feeling marginalized.

The crisis escalated when the Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Consortium United Front (SCACUF), an umbrella organization of different Anglophone separatists groups which until recently enjoyed only fringe support amongst Anglophone Cameroonians, unilaterally declared restoration of the region’s independence on 1 October 2017. The government’s response was brutal. Civilians—men, women and children—peacefully celebrating the declaration in the towns and villages of the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon were brutalized and killed on the streets and in their homes. As weak calls from the international community for dialogue went unheeded, hundreds—by some accounts thousands— of civilians were arrested and taken to detention centers in the French speaking parts of the country, while thousands more sought refuge in neighboring Nigeria.

Never in the 56 years of the union has Anglophone nationalism and self-consciousness seen such a surge.

The events of 1 October have widened the growing rift between English and French speaking Cameroon. Never in the 56 years of the union has Anglophone nationalism and self-consciousness seen such a surge. There are more calls than ever for resistance to any form of authority from the central government, which separatists describe as colonialist and annexationist. On the other side, inflammatory language, often bordering on hate speech, has also surged.

Often described as an island of peace and stability in an otherwise conflict-ridden central African region, how did Cameroon get to this point? How did simple demands for better working conditions for Anglophone teachers and lawyers turn into violent political unrest? What are the prospects for a peaceful resolution of the conflict?

As one of the measures to diffuse the situation, the government has so far created a bilingualism commission, suggesting that it sees the problem as being partly, if not only, a language issue. Others have framed it as a crisis of governance, more specifically a bad example of diversity management. Yet, any analysis of the source of Cameroon’s present predicament—or better still Francophone Cameroon’s recurrent problems with its restless Anglophone regions— cannot ignore the country’s political and constitutional history.

A failed decolonization project?

Part of the story begins on 11 February 1961 when the UN Trust territory of British Southern Cameroons, which constitute what is today the two Anglophone regions, voted in a UN organized plebiscite to ‘achieve independence by joining’ French Cameroon, against the only other option which was ‘independence by joining Nigeria’ (the peoples of British Northern Cameroon voted to join Nigeria). French Cameroon had earlier gained independence from France as ‘La Republique du Cameroun’ [The Republic of Cameroon] with Amadou Ahidjo as its President on 1 January 1960. The two Cameroons, formerly a German colony, were split and placed—first as a League of Nations mandate and later as UN Trust territories— under French and British administration respectively after Germany’s defeat at the end of World War I. For administrative reasons, Britain decided to integrate and administer its part of the possession with Eastern Nigeria.

It is tempting to argue that the current political crisis is a product of an ill-thought decolonization process.

Why Britain and the UN refused to consider warnings from some British MPs at the time to the dangers of merging the territories and demands from Anglophone nationalists for full independence as of right is now academic sport. Following the plebiscite, the next step was to determine how to concretize the outcome of the vote in line with international law. Of relevance here is article 76b of the UN Charter. It states, as the basic objective of the Trusteeship system, the advancement of peoples of Trust territories towards self-government or independence, as appropriate. With full independence not an option, the search for a solution that would secure the right to self-government for British Southern Cameroons in the future union with La Republique du Cameroun was on.

Towards this end, the UNGA adopted resolution 1608 of 21 April 1961, comprising a number of decisions which have been central to pro-independence activists’ case for external self-determination. Paragraph 4b set the date for the termination of the Trusteeship Agreement over British Southern Cameroons and independence of the territory through union with La Republique du Cameroun for 1 October 1961, in line with the results of February 11 vote. Crucially, paragraph 5 of the resolution invited Britain as the Trust Authority, the Government of the Trust Territory of Southern Cameroons, and the Government of La Republique du Cameroun to agree, before 1 October, on the ‘mechanics’ by which the declared policies and intentions of the parties will be implemented. The interpretation of the import of this paragraph is polemical. It is unclear what kind of obligation, if any, it imposed on Britain. It is also unclear what kind of ‘mechanics’ for implementing the declared intentions—whether a treaty of union or some other form of legal instrument—was envisaged. Pro- independence activists argue that the option ‘achieve independence by joining’ suggests that the mechanics had to, by necessity, be a Treaty of Union because the merger of the two Cameroons was envisaged as one between two equal states, rather than one state subsuming the other.

Be this as it may, what followed was solely a bilateral, instead of the trilateral process provided in the resolution, between an ill-advised government of the Trust Territory and a more experienced and French- advised Government of La Republique du Cameroun for a federal state. The terms of this merger were framed in a federal constitution drawn up in a constitutional conference in July 1961. Some critics, including interestingly some of President Ahidjo’s closest French advisers, characterized this document as the product of a sham constitutional process as the supposedly new Constitution was nothing more than the basic law of La Republique du Cameroun slightly adjusted to accommodate the joining entity without taking full account of the specificities of the two territories. They argue, crucially, that it violated the principle of equality of the two states.

The constitutional changes and political dynamics that came into play after the first decade of the Cameroonian federation have contributed to disillusionment in Anglophone regions.

Why Britain failed to take part in this process as provided by paragraph 5 of resolution 1608 remains unclear. Nonetheless, pro-independence Anglophone nationalists have seized on this procedural flaw to argue that resolution 1608 was not fully implemented and the union between the Trust Territory of British Southern Cameroons and La Republique du Cameroun could not have been properly constituted under international law. To buttress their point, they further emphasize that neither the government of Southern Cameroons nor its Parliament signed or ratified the Constitution, which bore only the signature of the President of La Republique du Cameroun. The Constitution was ratified and promulgated into law exclusively by the authorities of La Republique du Cameroun on 1 September 1961. Additionally, they point to the absence to date of any written agreement between the joining entities deposited at the UN Secretariat, an obligation imposed by UNGA Resolution 1541 of 15 December 1960, as evidence of their case.

Viewed from this perspective, it is tempting to argue that the current political crisis is a product of an ill-thought decolonization process for the Trust Territory of the British Southern Cameroons of which Great Britain and the UN, as Trusteeship Authority and the Supervisory Authority respectively, were key players.

Bad faith constitutionalism and manipulation?

Another historical aspect of this crisis is revealed by the constitutional changes and political dynamics that came into play after the first decade of the federation’s existence. The first defining change –perhaps most indicative of what was to come later —occurred in 1972. In a compelling argument emphasizing the need to maximize limited resources and to forge a closer and stronger union between the two historic peoples, President Ahidjo, who had all along remained at the helm of the state, convinced his Anglophone colleagues to abolish the federal system. As such, following a constitutional referendum on 20 May 1972, the Federal Republic of Cameroon was abolished and replaced with a unitary state: the United Republic of Cameroon. Moderate Anglophones who favour a return to the federal system of 1961 as the only way out of the current crisis see this as the beginning of today’s problems. Pro-independence Anglophones, however, see this as the constitutionalisation and consolidation of the annexation agenda of La Republique du Cameroun over Anglophone Cameroon, the foundations of which were laid at the sham constitutional discussions in July 1961.

The abolishing of the federation violated the constitution which placed an absolute prohibition on any form of amendment that impaired the federal form of the state.

Over the years, as relations with Francophone Cameroon started deteriorating over perceived systemic marginalization of English speaking Cameroonians, many Anglophone activists, in particular those leaning towards a return to the 1961 status, have questioned the 1972 vote. One challenge is premised on the conduct of the referendum process itself. It alleges that the procedure was carefully manipulated to ensure exactly the same outcome by printing the same answer options ‘Yes’ or ‘Oui’, on the ballot paper, to the referendum question of whether voters wished to abolish the federal form of state in favour of a unitary form of state. This may sound like legend. Yet, it is odd that the government— which has established a reputation for taking even on the most obvious fake news— has never confirmed nor refuted the allegation since it first surfaced. It has remained silent even in the face of supposed documentary evidence of fraud in the form of a ballot paper used during the vote. Legend (or not) aside, the 1972 referendum also fails substantive legal validity tests. The first is that the referendum as a way of amending the constitution violated paragraph three of article 47(3) of the federal constitution which stipulated that proposals for reform must be adopted by a majority vote of the members of the Federal National Assembly, provided, however that said majority included the majority of the representatives of each of the federated states. Crucially, the entire process violated article 47(1) of the federal constitution which placed an absolute prohibition on any form of amendment that impaired the federal form of the state.

Current President Biya's government removed the word ‘United’ from the official name of the country.

An additional legal challenge is grounded in the public and administrative law principle according to which an act constituted by a specific means or authority can only be validly abolished through the same means or by the same authority. These are the principles of congruent form or parallelism [parellélisme des formes et compétences]. Accordingly, since it was English speaking Cameroon which decided as part of the process of terminating British Trusteeship to join French Cameroon in a federal system, during a plebiscite in which only citizens of this territory voted, and also because they stood to lose more from the abolition of the federal system, the 1972 referendum should have been limited to citizens of the federated state of West Cameroon (official name of former British Southern Cameroons within the federal structure). Thus, it is possible to challenge the proper constitution of the present Cameroonian state.

Anglophone activists, while in agreement that the status quo is unacceptable, remain deeply divided.

To exacerbate the situation, a predominantly francophone government in 1984 led by Paul Biya, who succeeded Ahidjo in 1982, removed the word ‘United’ from the official name of the country. As such, the United Republic of Cameroon, purportedly established by the constitutional referendum of 1972 effectively reverted to being ‘La Republique du Cameroun’. Recall that this was the official name of French Cameroon following its independence from France and before reunification with British Southern Cameroon in 1961. Thus, Anglophone nationalists today consider the 1984 name change as constituting a constructive, unilateral withdrawal of French Cameroon from the union, thereby entitling Anglophone Cameroon to severe links and chart its own destiny. This may look like an unnecessarily emotive interpretation. Yet, it raises deep questions not only about the Anglophone identity within the Union but also official recognition and respect for that identity by the Francophone majority. Part of that identity, the common law and the educational systems, have come under increasing threat, culminating in yet another crisis between these two groups in 2016—when civil law judges and Francophone teachers were deployed to practice their trade in these regions without regard to their specificities derived from British heritage.

International response

Despite strong condemnations of the violence and calls for genuine dialogue from the UK, EU, UN, AU, the Commonwealth, la Francophonie and France, no serious effort has been made to force the government, which alone has the power of initiative to call for such dialogue on terms agreeable to both sides. The UN has asked the Cameroonian government to address the ‘root cause’ of the problem, suggesting it has a different understanding from the government of the fundamentals of the issue. Yet, it has conspicuously avoided articulating further on the term ‘root cause’. In its strongest statement on the crisis so far, the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights has recently said that the government of Cameroon must engage representatives of English-speaking Cameroon in a meaningful political dialogue, and immediately stop violations. Similarly, the AU through its political affairs department indicated that crises such as those presently afflicting Cameroon must be analyzed as an issue of self-determination rather than terrorism—a term preferred by the Government of Cameroon. In an even stronger and more direct statement, the AU’s Chairperson requested the conflicting parties to respect the boundaries as they existed at independence without articulating further. Considering the direct parties to the conflict have different understandings of what the root cause is, and that the boundaries at independence is a rather incoherent concept as both French Cameroon and British Cameroon gained independence on different dates, it would seem the international response has actually exacerbated the confusion.

What next?

At the moment, the crisis seems to have reached a stalemate with no clear end in sight. Anglophone activists, while in agreement that the status quo is unacceptable, remain deeply divided. One group seeks internal self-determination through greater autonomy for the regions, but with a specific preference for the federal system of 1961. Federalism in their view is a midway compromise between those (predominantly Francophones and regime apologists) who want to maintain the status quo—a decentralized unitary state— and the Anglophones who want outright independence. Previously in the majority, federalists as they call themselves, have lost significant ground, as a result of government mismanagement of the crisis so far, to the former. Within the pro-independence group, divisions are also rife. One factions seek international mediation and diplomacy as the way to independence. A more radical wing argues that absent outright armed conflict against the central government, independence will remain unachievable. The sheer imbalance of military capabilities between the two sides makes the success of the latter strategy questionable. Yet, it might pressurize the international community, more than ever, to force the government to make some reasonable concessions, more likely some form of greater internal autonomy such as federalism rather than outright independence.

Regime apologists see federalism as just another way of breaking up the country rather than a tool for managing diversity-driven conflicts.

However, incumbent president, Paul Biya—himself a key actor in the reunification politics of the 1960s and 70s— has always categorically maintained that neither is an option. Regime apologists see federalism as just another way of breaking up the country rather than a tool for managing diversity-driven conflicts. In the 199os, when this issue, which keeps recurring as an unpleasant ghost from the country’s past, threatened to plunge the country into conflict, the government introduced decentralization in the constitutional reforms of 1996 but then denied it in every aspect of its application. Yet more Francophones now seem to grasp the issue better than before, and are increasingly amenable to the idea of greater internal self-determination— beyond the current administrative decentralization — for the Anglophone regions as a workable compromise. Surveys show federalism is gaining traction, although differences remain on how the constituent units of that federal structure will or should be carved out. Either way, this will require a profound soul-searching and candid constitutional conversation about the cornerstones of such a compromise.

Presidential elections are scheduled for October 2018, and could offer significant prospects for a pathway out of the crisis. Most of the formal political opposition— including the once revered Social Democratic Front (SDF) party of John Fru Ndi which favors a federal system of government— remains in disarray, and too discredited to pose any real challenge to Biya. At the same time, Akere Muna, a well-known lawyer and anti-corruption activist from the civil society, with broad appeal and national and international pedigree is emerging as a serious contender. He has promised broad dialogue and a new republic based on a federal system, if elected.

President Biya's exiting the political stage may offer a genuine chance for real solutions to the crisis.

Two important factors must be considered though. First, the English-speaking regions may remain, physically and politically, an integral part of Cameroon. Yet the psychological divorce seems so profound that elections organized by central government are already being portrayed as an external event, irrelevant to the needs of the regions. The line between ‘them’ and ‘us’ seems inevitably drawn. Without the ability, willingness or strategy to mount a full-blown insurgency, pro-independence activists nonetheless want to make the regions ungovernable by all means. This means making it impossible to hold elections there or encouraging a general boycott. The new wave of guerilla style ‘hit and run’ strikes recently launched by more radical wings of SCACUF such as the Ambazonia Governing Council (AGC) on military targets is likely a step in that direction. It reinforces the ongoing civil disobedience campaign dubbed ‘ghost towns’. Second, a critical question is whether President Biya will stay or step down when his current term expires. At 35 years in power, Biya is one of Africa’s longest-serving head of state, but his exiting the political stage may offer a genuine chance for real solutions to the crisis, especially if he does so without seeking to replace himself with equally conservative and perhaps more hawkish elements of his regime. However, should he decide to stay in the race, this will dampen such hopes especially as the current electoral playing field and rules remain stacked against any challenger. While potential candidates are already lining up and slowly articulating their agenda, the President characteristically continues to play his cards close to his chest.

Yuhniwo Ngenge is a lawyer with expertise on constitutional, governance and political developments in Sub-Saharan Africa.