Political rights of Women in Egypt’s Second Republic: Ambitious Aspirations and Dismal Realities

Women took to the streets across Egypt and fuelled the 2011 revolution to a degree unprecedented in Egyptian history, at least partially, due to the lack of political equality in an authoritarian state. What is the status of women in Egypt four and half years after the January uprising? Did women achieve what they aspired to accomplish? How did constitutional texts and socio-political realities affect the struggle for political equality? Contrary to the high expectations that accompanied the uprising little was secured on the ground in the realm of women’s political rights.

Successive Egyptian constitutions granted women a number of socio-economic and political rights but the march for meaningful equality has faltered. Since 1952, policies of presidents Nasser, Sadat and Mubarak have contributed to a male-dominated bureaucratic political order, where women felt exceedingly marginalized and alienated. The substantial female participation since January 2011 promised to change the pervasive status quo. Egyptian women were part and parcel of the massive protest that swept Mubarak out of office in January 2011. In fact, it was a 26-year-old female activist, Asmaa Mahfouz, who has become the face of the call to bring people to the street. The video that fueled the Egyptian Revolution quickly went viral and inspired hundreds of thousands to take to the streets on January 25th, 2011.

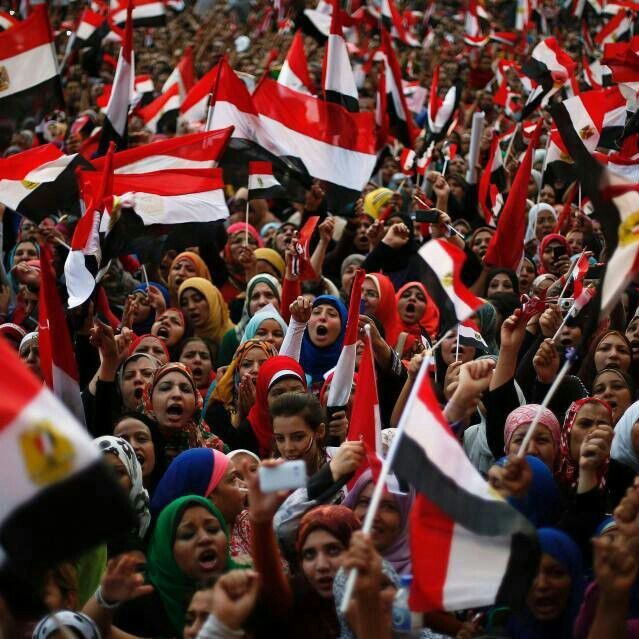

Women of the revolution demonstrated how Egyptian women felt empowered by the presence of women and the camaraderie that was the landmark of Tahrir. Young Egyptians hoped that the democratic model of the “republic of Tahrir” would be the model of Egypt’s second republic. The “new” socio-political order was thought to be a sharp departure from the repression and systematic marginalization of women. Women continued their public involvement during the transition process and the short reign of Mohamed Morsi. Moreover, women participated heavily in the June 30th, 2013 mass protests that were the pretext for Morsi’s removal and the installation of Abdel Fattah el Sisi as Egypt’s fifth president.

El Sisi suspended the 2012 Constitution that was drafted by an assembly selected by the 2012 parliament. The parliament at that time was controlled by Islamists and women were not adequately represented. All of these unfavorable conditions were reflected in the constitutional text. On January 18th, 2014, Egypt adopted a ‘new’ constitution. Article 11 could be considered the backbone of women’s rights as it underscores the twin-principles of equality and political rights, stressing the state’s responsibility to “ensure the appropriate representation of women in the houses of representatives, … guarantee women’s right of holding public and senior management offices in the State and their appointment in judicial bodies and authorities without discrimination.”

In his inauguration address, el Sisi acknowledged the vital role of Egyptian women and vowed to expend every effort so that women have a “fair representation” in elected and appointed posts. Despite this lofty language, little has changed on the ground. The constitutional text would not change actual conditions particularly if state institutions entrusted to implement it are still dominated by officials who perceive women’s rights as part of foreign agenda to undermine the Egyptian state and where women are denied the ability to lobby for their rights.

Women’s representation in elected assemblies at the local and national levels remains unsatisfactory. The regime has extended the tenure of the local councils across Egypt. The majority of members are male, despite the constitutional text that requires 25% female representation. At the national level, Egypt does not have a legislative assembly and the president assumes the legislative powers in addition to the executive authority. Parliamentary elections that should have taken place in March-April 2015 were suspended after the court ruled the electoral law unconstitutional. And the relevant constitutional provisions are not assuring either. Women lost their 64 seats quota (out of 518 seats) guaranteed in the 1971 Constitution. The so-called liberals, who constituted the majority of the army-appointed 50-member committee, objected to granting women such certain representation. Neither does the electoral law enacted by the president guarantee women a fair share. While the law mandated female presence on the electoral lists (7 out of 15 in smaller districts and 21 out of 45 in larger districts), this would have been ineffective for two reasons. First, the law did not require political parties to position women on prime spots on the list, allowing the placement of female candidates in the bottom of the list with no realistic chance of gaining seats. Second, proportional representation districts were only allocated for 120 seats of the 540 seats in the House of Representatives. The rest are allocated to first-past-the-post seats, where women rarely succeeded in the past. Most likely, cultural stereotypes would continue to limit women representation to its historically stumpy levels.

Representation in appointed positions at the cabinet level and below is no less troubling. El Sisi, despite his rhetoric regarding the role of women, did not see it fit to appoint a single female governor. The President of the National Council for Women, Mervat al-Talawy, generally a reliable regime supporter, condemned the government decision in a public statement. The number of women in the cabinet remained embarrassingly low for a country that granted women equal political rights more than half a century ago. Out of 34 cabinet posts women only have 4, roughly 11%, of the total council of minister seats. Furthermore, women were not granted access to the more powerful portfolios of defense, interior, foreign affairs, treasury, planning, industry or even education, health and housing. No women were appointed as deputy prime minister. Women remained confined to their traditional assignments of third-tier posts, holding the portfolios of Social Solidarity, Urban Development, International Cooperation and Manpower.

Representation in the judicial institutions continues to fly in the face of the constitutional text. Women’s representation in Egypt’s judiciary is only symbolic. Women are permitted to assume judgeship in the ordinary courts in insignificant numbers and are excluded from the public prosecution office and the Council of State. Female activists believed that the new constitution (Article 11) would change this. For the first time in Egypt’s constitutional history, the state committed itself to female representation in the courts. The High Judicial Council (HJC) agreed in February 2015 to appoint a new group of women judges. The HJC, nevertheless, did not accede to allow women equal access to the bench. The HJC interviewed female members from the ranks of the Administrative Prosecution Authority and the State Cases Authority, where women represent roughly a third of the corps. No females were permitted to compete for the entry exam. A tradition that has no basis in the constitution nor the Law of Judicial Authority. The same policies of Mubarak era persisted despite the constitutional guarantees. Even more troubling news came from the administrative courts. After the Constitution came into effect a number of recent female law school graduates attempted to apply for entry posts within the Council of State but were denied access to the applications. Mervat al-Talawy sent a communiqué to the Council objecting to this flagrant constitutional transgression. The Council judges, however, remain steadfast in their opposition to women’s entry into the administrative courts. A number of judges maintained that these constitutional articles do not “oblige” the Council to appoint women, adding that “current circumstances” prevent them from being judges. Some conservative judges even claimed that the idea of female judges is unacceptable in Shari’a Law. The regime, apparently, did not want to take a strong stand that could upset the judicial corps that is crucial to maintaining regime stability.

Furthermore, women were not spared by the regime’s repressive policies that have stifled the voices of dissent across Egypt. Meanwhile, civil society has been facing an unprecedented crackdown from the regime. Over 360 NGOs have been shut down for charges of ties to the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood. Women are suffering from a restrictive political climate. The near complete shutdown of the public space impeded political activism to secure women’s rights.

Many women were either killed or injured during the continuous clashes between security forces and protestors since July 3rd, 2013. Female activists, liberals and Islamists alike, were imprisoned, received lengthy sentences or were referred to military courts. More than 41,000 people have been arrested, charged or indicted with a criminal offense and exemplified how “mass protest was replaced with mass arrest.” The codification of repression is illustrated in the Protest Law, which enables the authorities to criminalize peaceful protests, and permits the security forces to use excessive and lethal force against peaceful protesters with virtual impunity. Targets of repression included not only Muslim Brotherhood members or sympathizers but also liberals, including scores of female activists. This included prominent human rights defenders Yara Sallam and Mahienour El-Massry. Asmaa Mahfouz was silenced after vicious attacks in the government-controlled media of treason and disloyalty to the country. The April 6 Youth Movement, which she helped found and which was critical for bringing young men and women to political life, is now banned.

In addition to a very restrictive political and civil sphere, sexual harassment has become even more pervasive. According to a survey released by UN Women, a staggering 99% of women in Egypt have suffered sexually harassment. (See UN Egypt calls for firm stand on violence against women.) To his credit, el Sisi has acknowledged the increasing levels of sexual violence against women, which is something no former president has ever acknowledged. The government has introduced stiff penalties for the perpetrators of sexual harassment: any verbal, physical, behavioral or online form of sexual harassment is punishable by six months to five years in prison and a fine up to 50,000 L.E ($6250). The enforcement of the law, however, remains feeble and combating harassment does not appear to be prioritized by domestic security forces busy with cracking down on peaceful protests and combating violent extremists.

Twenty months after the adoption of the constitution, little has changed. In fact many of the gains in the realm of political participation and freedom of speech that Egyptians have exercised since Mubarak’s abdication, seem to have been lost. This has hindered women’s ability to mobilize in order to secure their political rights. The current regime seems to be largely a continuation rather than a departure from Egypt’s old order. Despite official gestures to enhance the conditions of women, in many aspects women could be considered worse off than under Mubarak.

The future of women in Egypt remains uncertain and the road to equality is hindered by a plethora of political landmines and socio-economic obstacles. The realisation of women’s political rights would require drastic changes in the polity and the society that far exceeds the constitutional text. It requires a democartic political process, a more egalitarian society, a liberal interpretations of the religious texts, public officials, who actually support gender equality and women’s groups that connect with the masses. All these conditions continue to lack in 21st century Egypt, where the genesis of the problems remains the same.

Mahmoud Hamad is an associate professor of political science at Drake University (USA) and at Cairo University (Egypt). His teaching and research interests focus on Middle East politics, comparative judicial politics, civil-military relations as well as religion and politics. Mahmoud is the editor of Elections and Democratization in the Middle East: The Tenacious Search for Freedom, Justice, and Dignity (Palgrave, 2014). He is also the author of Generals and Judges in the making of Modern Egypt (in progress).