Italy towards institutional re-design: a constitutional and political marathon

The constitutional revision process continues to trigger hot parliamentary debate in Italy. The Constitutional Amendment Bill introduced by the government of Matteo Renzi sets out an ambitious plan of reform. If adopted, it would revise the functions and structure of the Senate, simplify the legislative process, and change the distribution of powers between the national and regional levels of government.

Modernizing the Constitution - Ageless Challenge and Damned Temptation

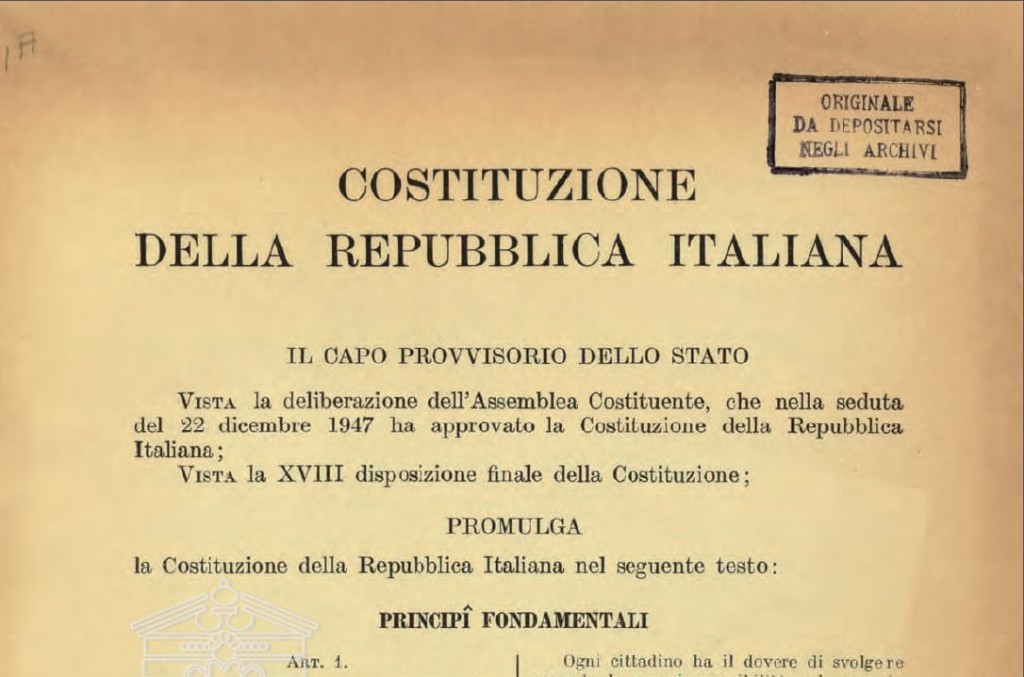

The Italian Constitution was adopted in 1948, following the restoration of democracy after twenty traumatizing years of dictatorship under Benito Mussolini. The primary concern of the Constituent Assembly was to provide guarantees against the excessive concentration of power in order to protect democracy against any possible return to authoritarianism. The institutional design of the constitution embodied this concern for the diffusion of power through the adoption of symmetrical bicameralism, with two chambers of equal power, both popularly elected by proportional representation.

In practice, however, the constitutional diffusion of power has been seen not as a guarantee of good governance but as a hindrance to it. The Constitution has been blamed for institutionalizing policy stasis, instability, and weak ineffectual governments. The question of whether to keep ‘symmetrical’ bicameralism, in particular, has never been truly settled.

Despite the overall agreement on the need for constitutional reform, political instability and failure to broker consensus on the exact ways in which such reform should be brought about has frustrated efforts to pass constitutional amendments. During the past 30 years, a variety of attempts have been made but all - including the work of three parliamentary bicameral commissions, the expert committee of PM Berlusconi in 1994 as well as the ‘wise men’ appointed by President Napolitano and PM Letta, in 2013 – have led to failure.

Another difficulty is posed by the lengthy and burdensome amendment process set forth by Article 138 of the Constitution. This requires the two Chambers to approve the same text a total of four times, with a three-month reflection period after initial approval, and to endorse the amendment with an absolute majority during the last two readings. If the bill has not been approved by a two-thirds majority, a referendum on the amendment may be demanded by any five of the country’s twenty regional councils or by 500,000 voters.

The Bill - An ‘Imposed’ Constitutional Revision?

Despite these hurdles, and after so many failed attempts to

reform the Constitution, the current Amendment Bill seems to have a real

possibility to succeed. It

has already been approved by the Senate in August 2014 and by the Chamber of

Deputies in March 2014. It is now set for a second vote in the Senate to

approve changes introduced by the Chamber. Nonetheless, the highly contested

Constitutional Amendment Bill still has to face several legislative

(and political) challenges before its final

approval. Indeed, the majority which approved the first reading

at the Senate in 2014, initially set up by PM Renzi, has already reduced.

Concerns arise regarding both the process and the substannce of the reform. Procedurally, the government chose to avoid any preliminary public, expert or parliamentary consultation or general debate on the contents of the reform prior to drafting the Constitutional Amendment Bill and submitting it directly to the Senate. The parliamentary process has not only been characterized by breaches of parliamentary customs by the government to accelerate the process, but has also brought about disputed political deals, including a new Electoral Law to cement the parliamentary majority of the resulting ruling party. Given the failure of previous administrations to forge alliance and build consensus on the contents of constitutional reforms, the ongoing revision appears to avoid political dialogue or parliamentary debate outside governmental circles in order to decrease the chances of failure. The lack of inclusiveness of the amendment process has increasingly created the impression of an ‘imposed’ reform.

Stability

vs. Representativeness? - Perspectives on Differentiated Bicameralism

The main substantive change proposed in the Constitutional Amendment Bill is to simplify the institutional set-up, primarily by differentiating the functions of the two chambers. The overall aim is to overcome legislative ‘paralysis’ so often brought about by the symmetrical bicameral design. Instead of an equal division of the legislative power between the two chambers, if the Amendment passes, the legislative power will be concentrated in the Chamber of Deputies. The Chamber, with a few exceptions, will also enjoy supremacy over the Senate and hold the exclusive power to cast a vote of confidence initiated by the government.

According to the proposed Amendment, the Senate will no longer be elected directly, but will be composed of regional councilors and mayors. The number of members will be reduced from 315 to 100. Nevertheless, it will continue to play a role in the election or impeachment of the President of the Republic, in the election of the Constitutional Court Judges as well as the members of the Supreme Council of the Judiciary. The differentiation is due to the new role of the Senate throughout the legislative process. There will be only a few “fully bicameral” laws that will continue to require the equal support of both chambers to pass. Although the Constitutional Amendment Bill does not define fully bicameral laws explicitly, it requires such legislative procedure for laws that concern regions and local entities, Senate elections, Italy’s EU membership, constitutional amendments or “constitutional laws” as defined by domestic law. Given that the Amendment will also re-shape the legislative competencies between the central government and the regions, with the abolition of the so-called concurrent competencies, the Senate will be transformed into a regional chamber, where nevertheless local authorities will continue to be involved in the new legislative process. This modification seeks to give more consistency to the two legislative dimensions and to clarify the competencies assigned to each entity in order to put an end to continued competency clashes - an issue that has been disputed before the Constitutional Court for decades.

Besides

the procedural and substantive aspects of the Constitutional Amendment Bill

itself, the new Electoral Law has been closely linked to the reform process. Nicknamed

the “Italicum”,

the law was adopted earlier this year in a highly

contested atmosphere due to the government breaching yet

another parliamentary custom.

This Electoral Law appears to support the concentration of power in the hands

of the winning party through a majority bonus that would guarantee 55% of the

seats in the Chamber of Deputies to the party winning the plurality of votes. Besides

enabling the winning party to dominate the only national chamber, the Amendment

would also allow the Prime Minister to govern without forging alliance with any

other party.

The constitutional amendment and the electoral reform have been pushed forward hand-in-hand, with the presumption that by the time the new Electoral Law comes into effect in July 2016, the Constitutional Amendment Bill will already be passed. However, since the amendment would entail the replacement of a directly elected Senate with an indirectly elected one, the new Electoral Law does not regulate the election of Senators. This might leave the country in a constitutional and institutional crisis, should there be a delay in the constitutional reform process or a governmental crisis resulting in the dissolution of the Parliament; something Italy is known for, having had 63 governments in the past 69 years.

Overall, the reform proposes

an asymmetric bicameralism, with a strongly majoritarian parliamentary system

as a result of the Electoral Law, where the Chamber of Deputies, the only ‘national’

chamber, would enjoy supremacy over the Senate. The reform would introduce the

direct election of the Prime Minister, who will be only accountable to the

Chamber of Deputies whose majority would be guaranteed through a considerable bonus in favour of the winning party list. This would entail the strengthening

of the Executive through bringing the prime ministerial role from the President

of the Council of Ministers closer to the Premier model. Just as the Constituent Assembly

over-compensated for dictatorship, and created a system in which power was too

diffuse, could these reforms also over-compensate for the years of stasis and

instability by creating an excessive concentration of powers

with few effective checks and balances?

The

continued legitimation crisis of the Government and the Parliament supports the

need for revision and, at the same time, weakens popular trust in the actors participating

in the reform process. After the Monti and the Letta goverments, Renzi’s is the

third

government in a row that was not directly endorsed by an

electoral mandate. Parliamentary legitimacy is called into question as well,

given that the Parliament was elected according to the previous Electoral Law

that was declared unconstitutional

by the Constitutional Court. To remedy a future legitimation crisis, the Constitutional

Amendment Bill would also introduce a novel preliminary judgment procedure by

the Constitutional Court on the legality of future electoral laws adopted by

the Parliament, provided that a minimum number of parliamentarians request the constitutional review before the law enters into force. Notwithstanding some favourable proposals, a group of prominent

constitutionalists, including former Constitutional Court Judges, already launched an appeal against the

Constitutional Amendment Bill.

The Renzi administration’s overall argument in support of the Bill is that, while the new Electoral Law would finally bring stability and governability to the Executive, the constitutional reform would guarantee efficiency in the Legislative. The Government has pledged to put the Bill up for referendum, provided that it is adopted in the Parliament. And hopes are high that despite all criticism, the reform will manage to bring efficiency through the institutional re-design and stability through the majoritarian system. Another welcome feature of the proposed Amendment is the heightened role of the regions in line of Article 5 of the Constitution, which “recognizes and promotes local autonomies” and with Article 114 that emphasizes the autonomy of local and regional authorities.

The Constitutional Amendment Bill is expected to be adopted by July 2016. Parliamentary clashes and tensions between the Parliament and the Government are ongoing, yet the political determination of Prime Minister Renzi continues to fuel the reform process. The youngest PM in Italian history is determined to succeed, where all his predecessors have failed. PM Renzi, who has become known as the ‘demolisher’ of the old political establishment, has so far managed to push through structural reforms rapidly, but this time might have to recognize that political dialogue is unavoidable to build consensus on constitutional changes.

The current design of Italian bicameralism is obsolete and is one of the causes

– yet not the only one – that have frustrated efforts to bring about structural

reforms. This reform, despite all procedural and substantive concerns, seems to have a reasonable chance to modernize the institutional system and to solve longstanding critical issues. However, it would

benefit from increased checks and balances and a more careful consideration of the Electoral Law's effect on the constitutional reform. Today Italy is closer to bringing

to completion a constitutional reform process than any time in the past 60

years. Whether it will be a step forward for Italian democracy will largely

depend on whether the Amendment can strike a fair balance between stability and

representativeness.