Uganda’s age limit petition: Constitutional Court demurs on substance, cautious on procedure

The Ugandan Constitutional Court has upheld the removal of age limits on presidential candidates, effectively allowing Museveni to extend his more than three-decade regime. While it invalidated the amendment extending parliamentary and local government terms, it was mainly based on procedure, rather than a commitment to fundamental features of the Constitution. The Ugandan experience demonstrates the current inadequacy of parliamentary and judicial checks on the incumbent president who enjoys unfettered executive power. New tools are needed to ensure a more effective veto on the enactment of self-serving, capricious and unpopular reform initiatives by the entrenched incumbents – writes Karoli Ssemogerere.

On 26 July 2018, the Ugandan Court of Appeal, sitting as a Constitutional Court, delivered judgment in a combined petition challenging the constitutionality of the Constitution (Amendment) Act, No. 1 of 2018. The amendment, which was passed in December 2017 and gazetted in January 2018, has three major provisions. The first repeals and replaces the five-year term for both members of parliament and elected local government officials with seven years. A transitional provision stipulated that the new terms would apply to members of parliament and local officials elected for a five-year term in February 2016.

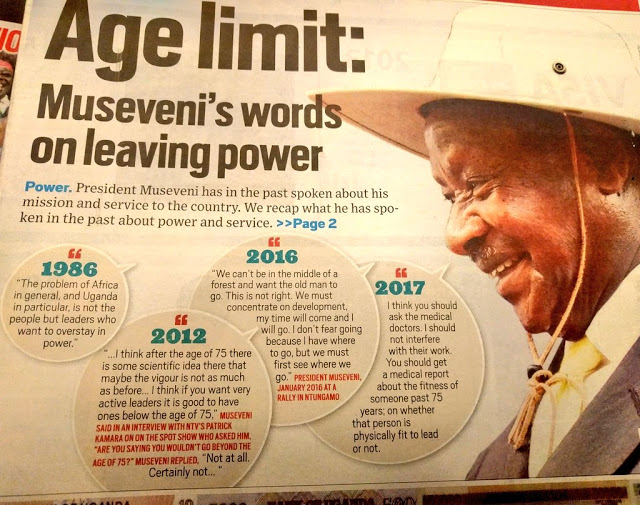

The second measure repealed the minimum and maximum age limits in the constitution for the Ugandan President and Local Government chairpersons. The principal beneficiary of this measure is incumbent President Yoweri Museveni, who will officially attain the age of 75 years in August 2019, and has been in power for more than three decades. Absent this change, Museveni is barred from being nominated for re-election in 2021 at the expiry of his current five-year term. Thirdly, the amendment returned the two-term limit on the occupants of the presidency, which was removed in 2005, and further entrenched this provision, requiring prior to amendment both a two-thirds majority vote in parliament and approval in a referendum.

A minor measure amends the Constitution to increase the time period to file a presidential election challenge before the Supreme Court from 10 to 15 days, for the court to render a decision from 30 to 45 days, and for holding a re-election from 20 to 60 days. The changes gave effect to recommendations made by the Supreme Court in an election petition following the 2016 presidential elections (Amama Mbabazi v Electoral Commission & Another Supreme Court Election Petition), considering that all presidential election petitions since 2001 failed on the basis of insufficient time to file evidence supporting them coming from all over the country. This measure was mostly ignored by all parties in submissions before the Constitutional Court, although it was affected by the five petitions which sought to strike out the entire amendment.

The Constitutional Court upheld the amendment removing age limits in a 4-1 decision, despite recognizing interference in the consultation process.

The Constitutional Court upheld the amendment removing age limits in a 4-1 decision. The Court found the process of amendment in relation to the age limit proper, despite recognizing the imperfections. It also ruled that the age limit was not a core or entrenched feature of a constitution that would require a constitutional referendum. Nevertheless, the Court by a 5-0 majority found that the extension of parliamentary terms and the reinstatement of presidential term limits were enacted in violation of parliamentary rules of procedures, and by implication the constitution, that required them to be formally published in the form of a bill, interrogated by a parliamentary committee, and reported on by the committee of the whole house prior to being debated, passed and enacted into law. The Court noted that, whereas there was no express prohibition on retroactive legislation, the retroactive effect of the amendment extending parliamentary terms violated the sovereignty of the people, who had voted for the members for a five-year mandate. The dissenting judgment struck down the whole amendment because the entire process had been tainted by the same lack of consultation, noting the insufficiency and lack of seriousness of the entire process and failure to employ the provisions of the Commissions of Inquiry Act, Cap 166.

The Court unanimously found that the two extraneous amendments, extending the parliamentary/local government term and reintroducing presidential term limits, were introduced during the committee stage and skipped all the mandatory procedures of being introduced as a fresh bill or a motion under the applicable parliamentary rules of procedure. The court further found there was no justifiable basis of this, and that no public consultations were recorded on this subject. The Court found that this failure to consult deprived the public of the constitutional right to a fair hearing. By arrogating themselves the right to extend the term of the current parliament without a fresh election or approval of voters, parliament also violated constitutional provisions for simultaneous elections, and a fixed parliamentary term, which could only be extended for no more than six months in a state of emergency.

Amendments extending the parliamentary/local government term to seven years and reintroducing presidential term limits were unanimously invalidated.

The Justices unanimously agreed that impugned provisions requiring a referendum for certain provisions (including the unpublished harmonization of the seven-year term for the president, parliament and local government) had financial implications, and violated restrictions on parliament’s competence to legislate on financial matters in article 93 of the Constitution and the Public Finance Management Act, 2015. Legislation with financial implications must be accompanied prior to tabling in parliament by a mandatory certificate of financial implications. During court testimony, several key government officials led by the Secretary of the Treasury failed to convince the Court that the certificate tendered in court had not been backdated.

The Court unanimously found that the police and the state had interfered with the consultation activities of a few MPs. Ugandan police routinely rely on the Public Order Management Act, 2013 to issue illegal directives scuttling public meetings. However, the majority ruling found that this was not enough to render the entire amendment a nullity. Led by Justice Kasule, they applied the doctrine of severance to save the core proposal in the original bill – the amendment removing age limits, and strike down the other reforms. The Court further held that the violent parliamentary scenes and forcible removal of some MPs during the parliamentary debate did not fundamentally undermine the validity of the core amendment.

Cautious on procedure, reluctant on substance

The Court made a commendable effort to identify the major precepts underlying the constitutional order in Uganda. Deputy Chief Justice Alphonse Owiny Dollo, a former politician and Minister of State of Foreign Affairs, noted that some of these precepts had been subjected to dilution through amendments prior to their being tested. The Court discussed the ‘basic structure doctrine’ whose core principle is that there are fundamental building blocks in a constitutional order that cannot be amended at whim without upsetting the entire constitutional order. This basic structure doctrine may be linked to the fundamental features recognized in the 1993 Report of the Uganda Constitutional Commission, including the separation of powers, democratic governance and the independence of the judiciary. In particular, the Commission’s report noted the importance of ending ‘the phenomenon of self styled life presidents’ through term limits. Nevertheless, this issue seemed to be completely swept away in the Court’s final ruling as the Deputy Chief Justice simply noted that several well-intended provisions of the 1995 Constitution had not been allowed to function. This was an allusion to the removal of the two term presidential limits by parliament in 2005, which denied Uganda a chance to witness its first peaceful change from one president to another.

Museveni has criticized the decision and indicated that the reforms will be pursued, 'with or without courts'.

The Court concentrated on a scrutiny of the tabling, committee stage, debate and enactment first, then a harmonious interpretation of the various affected provisions of the constitution, restraining itself from raising a ‘political’ question on specifically why the Constitution has faltered in its primary objective to attain peaceful and orderly succession to power. The Court was timid and reluctant to apply on a wholesome basis the basic structure doctrine, perhaps wary of its prior confrontations with the executive. President Museveni has on numerous occasions confronted the courts head on, if he does not have his way. Indeed, following the recent decision, the President stated that judges were not the ones in charge of the country, and that the annulled amendments will be pursued, ‘with or without courts’.

In a 2004 decision, the Supreme Court - the highest court - found that parliament could involuntarily ‘amend’ the constitution by ‘infection’ where the net effect of one amendment could end up by amending by implication or infection other provisions of the constitution. In certain instances, these infected amendments require more stringent amendment procedures, for instance a referendum or a vote by 2/3rd of the district councils. Where such was triggered, an amendment that doesn’t comply with the more onerous standards cannot stand. The doctrine of infection was the first attempt to categorize certain provisions as fundamental building blocks of the constitution in line with the Odoki report, which would require more stringent amendment requirements, including a constitutional referendum. The 2018 decision has in addition emphasized the importance of public consultation in constitutional amendment processes. It nevertheless failed to review the substance of the constitutional amendments.

Despite discussing the concept of the basic structure doctrine, the Court failed to review the substance of the constitutional amendments.

The Court’s reluctance is in line with a lapse in the constitutional regime since 2002 when government appointed the Ssempebwa Constitution Review Commission to study a limited number of proposed amendments to the Constitution and ended up proposing deletion of presidential term limits, removing the only ‘safety’ in ensuring automatic political transition in Uganda. In 2005, parliament amended the Constitution. Government torpedoed the work of the Review Commission by introducing at the end of public consultations a proposal to delete presidential term limits as an offset to allowing the return to a multi-party system (ending the ‘Movement’ system – a purported no-party system). This matter is yet to be litigated decisively as it directly touches on the recorded views of the population that were collected during the tenure of the Review Commission.

The Supreme Court has feebly attempted to address incidents in Uganda’s notoriously violent election system. In 2001 and 2006, the Court upheld the re-election of the President even after noting widespread use of violence and other abuses of incumbency during the elections. In 2016, the Supreme Court went further allowing to hear a presidential election petition by a second runner up while the immediate runner up, Col. Kizza Besigye, was being held incommunicado at his home unable to consult his lawyers on whether to file an election petition.

A return to political realism, expediency, prospects on appeal?

Ugandan courts have struggled with the central issue of orderly political succession. The limits on presidential tenure, in the form of presidential term and age limits, were included in the original version of the constitution to moderate the influence of the president, the sole authority in whom executive power is vested, conscious of the historical usurpations by Uganda’s post-independence presidents of all state power. Unfortunately, the term limits were removed in 2005. The Court’s upholding of the amendment removing presidential age limits has legitimated the demolition of the last potent hurdle against Museveni’s life presidency.

Museveni’s long presidency has allowed him to dominate all institutions, including appointing government officials to the highest courts.

Museveni’s long presidency has allowed him to dominate all institutions, including the highest courts. As such, while an appeal still lies to the Supreme Court, the fact that it is packed with former politicians and state functionaries is likely to color the tone of the appeal. The rise of politicians to prominence in the judiciary has become a major threat to its independence. The superior courts are home to a former Attorney General, two former ministers (the third retired as Deputy Chief Justice in 2017), a former National Political Commissar of the ruling party, a former Director of Public Prosecutions, two former deputy Directors of Public Prosecution, two former Inspector Generals of Government etc. These have stifled independent voices as prior contact places them in a conflict of interest to defend decisions of a government they once directly worked for. The political imbalance is a major problem for the credibility of the highest court and how it reflects Uganda’s heterogeneous society and diverse political views.

The unintended long presidency, precipitated by the 2005 amendments to the constitution, has just worsened with the 2018 amendment. The unfettered executive power has crippled the most fundamental constitutional checks on abuse of power. Bolstered by a three quarters majority in Parliament, the president enjoys a big sway over its agenda and, by remaining the sole appointing authority of judges on advice of the Judicial Service Commission, has been able to fill the courts with sympathetic appointees whose tenure on the courts will last decades.

The invalidation of the term extension, while upholding the age limit removal, was a futile attempt to balance principle with pragmatism.

The Court’s decision to invalidate the term extension, while upholding the age limit removal, was a futile attempt to balance principle with pragmatism. While it developed new jurisprudence on application of the basic structure doctrine, it missed a final chance to entrench the findings of the Odoki Commission which had sternly warned against the above events happening. Even the future impact of the jurisprudence, where the lack of popular participation may provide ground for future blocking of amendments, is unlikely to be of practical utility, as the court approved the sham consultations in relation to the age limit bill in disregard of evidence indicating that the populace was opposed to the removal of the age limits. The reluctance to scuttle the age limit amendment means that the only check on government power resides in the electorate. The lack of a level playing political field, and outright electoral manipulations, undermine the checking power of even the people in whom ultimately sovereignty is claimed to reside. The decision may have effectively confirmed the unlimited powers and influence of Museveni.

The experiences may indicate that the protection of constitutional safeguards requires the empowerment of the political minority to refer constitutional amendments to a referendum.

The Ugandan experience indicates that parliament, and the courts, may not be solely relied up on to protect the constitutional dispensation against executive entrenchment. In some countries, instead of mandatory referendums (or in combination with mandatory referendums in relation to some provisions), the constitution empowers a certain percentage of the political minority in parliament to request the referral to a referendum of proposed constitutional amendments approved by the required parliamentary supermajority. Uganda unfortunately does not have this procedure to escalate approval or voting requirements. This procedure is flexible enough to enable uncontroversial amendments to be passed without resort to a referendum, with its resource, logistical and security challenges, while encouraging political deliberation and consensus in relation to controversial provisions. In the absence of such broad consensus, the people would have the direct say to decide on the disputed issue. In addition to claiming better democratic legitimacy, such a process creates discretionary but potent veto points to block self-serving, capricious or unpopular amendments.

Karoli Ssemogerere is an international lawyer, legal consultant and columnist. He has appeared before the Ugandan Supreme Court, and is a former Supreme Court Law Clerk and law lecturer.