Triple Talaq: Personal Law and Colonial Shadows in Contemporary India

Following failure to agree on the regulation of personal law, Indian constitutional drafters deferred the issue of a Uniform Civil Code. While the deferral paved the way for the adoption of the constitution, it should have come with a deadline. The absence of such a deadline has led to a political stalemate that continues to subjugate fundamental rights to personal law, which both disempowers women and perpetuates colonial legal frameworks - writes Arundhati Katju.

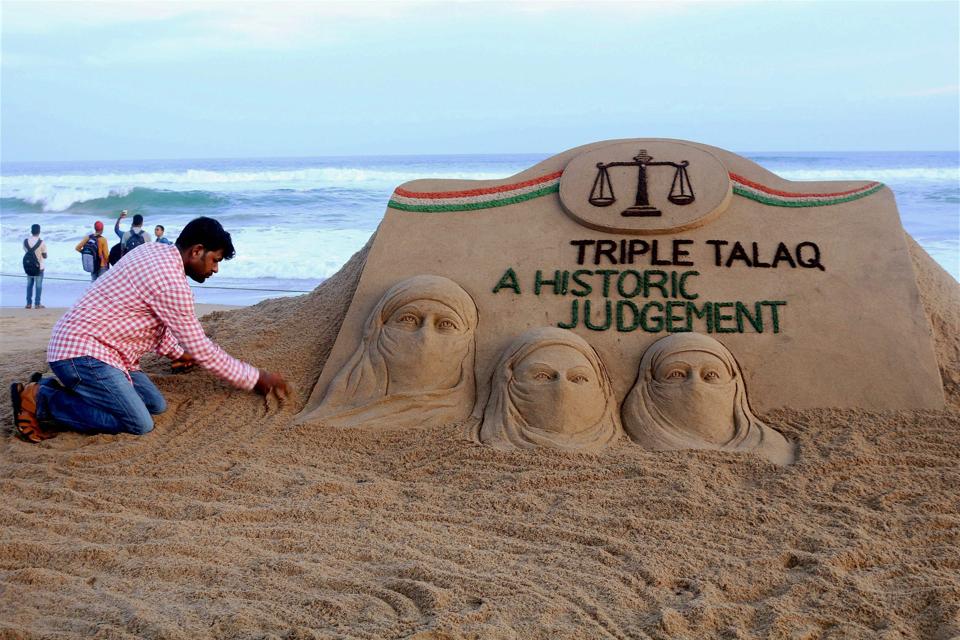

In August 2017, the Indian Supreme Court struck down the practice of Triple Talaq, which allowed Muslim men to divorce their wives by pronouncing ‘talaq’ (‘I divorce you’) three times. Beyond the immediate issue of addressing the acceptability of the practice in Islam, the case refocused an old debate on the extent to which religious laws governing personal matters are subject to review based on constitutional standards, especially fundamental rights provisions, and the need for a uniform civil code.

At independence, the Indian Constituent Assembly pragmatically answered only those questions of minority accommodation that could be resolved at the time and deferred the more contentious issue of the adoption of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC). Article 25 of the Constitution secured freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice and propagate religion to all citizens, both majorities and minorities. By stopping short of express protections for religious personal laws, it paved the way for their codification and eventual reform. Instead of forcing the UCC issue, the constitutional scheme enjoined the state to adopt a UCC under Article 44, in a chapter of the constitution dealing with ‘Directive Principles of State Policy’. Unlike the fundamental rights, these state policies are not justiciable. This constitutional design has been praised for finding incremental solutions while allowing the Constituent Assembly to move ahead with the all-important task of getting the Constitution done.

While deferral can be considered a successful technique of constitutional drafting, it runs the risk of leaving the deferred question unresolved if ordinary legislative or judicial processes prove inadequate. Although the Indian constitutional framers are not to blame for the inadequacies of future generations, deferral had two shortcomings even at the time: firstly, deferring the adoption of the UCC essentially perpetuated colonial legal frameworks by allowing the personal law system to continue. Secondly, deferral protected religious freedoms at the cost of women’s rights.

The Supreme Court has held that Sharia courts have no legal sanction and their fatwas are not legally enforceable.

This uneasy resolution of the personal law issue has been highlighted most recently in the Indian Supreme Court’s August 2017 judgment in Shayara Bano v Union of India, where a five-judge bench of the Indian Supreme Court struck down the practice of triple talaq by a tight 3:2 vote. Under the Shariat, divorce takes place instantly when a Muslim husband pronounces ‘talaq’ three times in one sitting. The practice of triple talaq has been outlawed in many Muslim countries, including Pakistan and Bangladesh. In India, the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 (‘the Shariat Act’), a colonial-era statute, provides that Muslims will be governed by their personal law (i.e., the Shariat) in questions of marriage, divorce, and succession. The Bano Court could not achieve a clear majority on the key questions before it, instead deciding the case through three plurality opinions. The issues on which the plurality opinions split show how the Court still grapples with issues left unresolved by the ‘deferral’ technique of constitutional drafting.

Secular Courts, Religious Laws

The Shayara Bano case highlighted religious tensions from its very inception. The issue was taken up suo moto by a two-judge bench of the Court in a completely unrelated case regarding the share of Hindu women in Hindu Undivided Family property. One of the judges who made the reference, Adarsh Kumar Goel, was a former General Secretary of the All India Adhiwakta Parishad, the lawyers’ wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the parent organization of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). When the Bano bench was eventually constituted, it consisted of one Hindu judge and four judges belonging to different religious minorities.

The entire judgment is silent on the colonial origins of the personal law framework.

By staffing the bench with judges from different religious backgrounds, the Court cut short the argument that Hindu judges would be imposing their views on the Muslim minority. The All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) nonetheless argued that the Supreme Court should not interpret the Shariat. Accepting this argument, Justice Khehar, speaking for himself and Justice Nazeer, declined to decide between hadiths expressing different opinions on the validity of triple talaq.

The Court still had to confront the question whether triple talaq is an ‘essential religious practice’. While Article 25(1) protects the right to ‘profess, practice and propagate’ religion, Article 25(2) enables the state to regulate ‘secular activity which may be associated with religious practice’. This has led to a line of Supreme Court decisions that call on constitutional courts to determine what constitutes an ‘essential religious practice’, which are left for religious regulation. Although there are no formally established Sharia Courts in India, the Imarat-e-Sharia of different states have established Dar-ul-Qazas where trained Qazis administer justice to Muslims as per the Shariat. However, the Supreme Court has held that these courts have no legal sanction and their fatwas are not legally enforceable. Regular courts may have to interpret religious law when issues arise in cases before them during the exercise of their statutory or constitutional jurisdiction.

In Shayara Bano, the bench was divided on the question whether talaq is an essential religious practice. Justices Nariman, Lalit and Kurien took the view that triple talaq, being permissible in law but unQuranic, is not an essential religious practice and therefore is not protected under Article 25(1). Differing from this majority, Justices Khehar and Nazeer held that triple talaq was an integral part of religion for Hanafi Sunnis.

Given the high variation between laws and custom in different regions, and to lessen their dependence on ‘native’ clerics, the British were keen to codify Hindu and Muslim law.

The judges then had to determine whether personal law is ‘law’ under Article 13 of the Constitution, which makes ‘laws’ subject to the test of the fundamental rights. Here, Justices Khehar, Nazeer and Kurien endorsed a decision of the Bombay High Court in State of Bombay v. Narasu Appa Mali which held that personal laws are not ‘law’ under Article 13 of the Constitution and, therefore, are not subject to fundamental rights analysis. Justices Nariman and Lalit sidestepped this question by proceeding directly to the fundamental issue whether triple talaq was personal law at all. They held that Section 2 of the Shariat Act recognized and made Shariat (including triple talaq) the rule of decision where parties were Muslim. Shariat was adopted in Indian law by a statutory mechanism and was law under Article 13. Here, Justices Nariman and Lalit were in the minority, though their interpretation appears logical and lucid. Justices Khehar, Nazeer and Kurian resorted to the maneuver that the Shariat Act did not legislate on the Shariat, rather, merely made Shariat (rather than custom) applicable to Muslims.

History Repeats Itself

Most surprisingly, the entire judgment is silent on the colonial origins of the personal law framework. The Court would have benefitted from examining these origins, as some of the questions that it grappled with are as old as the history of colonialism in India.

As the East India Company gradually expanded the reach of its courts in India, questions arose regarding which laws would apply to the ‘natives’. Warren Hastings, Governor of Bengal, introduced a Plan that was later incorporated under Article XXIII of the Regulating Act, 1773:

(I)n suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste, and other religious usages and institutions, the laws of the Koran, with respect to Mohammedans, and those of the Shaster with respect to the Gentoos, shall be invariably adhered to; on all such occasions, the Maulvies or Brahmins shall respectively attend to expound the law, and they shall sign the report, and assist in passing the decree.

The Hastings Plan thus required Maulvis and Brahmins to remain physically present in court to aid British judges in interpreting Hindu and Muslim law. Given the high variation between laws and custom in different regions, and to lessen their dependence on ‘native’ clerics, the British were keen to codify Hindu and Muslim law.

While ostensibly applying religious law, the Hastings Plan gradually contracted the sphere governed by religion. Religious law had originally governed all spheres of life, but was now restricted to matters of ‘inheritance, marriage, caste, and other religious usages and institutions’. Hindu and Islamic criminal and evidence laws were superseded entirely by the Indian Penal Code, 1860 and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Economic transactions, which were originally governed by religious law and kinship ties, were eventually taken out of the purview of personal law. With time, the Hindu Undivided Family was regulated by colonial law, and a slew of legislation replaced traditional economic units: the Indian Companies Act, 1882, the Indian Income Tax Act, 1886, and the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881.

Further, despite their avowed intent not to interfere with personal law, the colonial government passed many statutes on issues of marriage, divorce and succession - the Indian Divorce Act, 1869, the Indian Christian Marriage Act, 1872, the Anand Marriage Act, 1909, the Indian Succession Act, 1925, and the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936, and the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939.

Hindu Men Saving Muslim Women from Muslim Men?

The triple talaq issue gave the Hindu right-wing BJP government the opportunity to position itself politically as the savior of Muslim women. Paradoxically, BJP government now speaks the language of progressive politics and gender equality in calling for the adoption of the UCC. In Court, the Attorney General made arguments that one expects to hear from feminist lawyers: that Muslim women were suffering discrimination on account of their religious identity, that dignity and gender equality were ‘non-negotiable’, and, quoting Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, ‘patriarchal values and traditional notions about the role of women in society are an impediment to achieving social democracy’. Following the judgment, the BJP tried to pass the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights in Marriage) Bill, 2017, criminalizing triple talaq. Although this drew protest from the AIMPLB and some women’s groups, the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, one of the Petitioners before the Supreme Court, supported criminalization, though it wanted the criminal sentence to be more lenient. Shaista Amber, President of the All India Muslim Women Personal Law Board, criticized the AIMPLB, asking: ‘Why don’t they consider Muslim women as equal partners … Why do they want to create a communal feeling among Muslims when the society is going for reforms?’

The conflict between group rights and women’s rights is not limited to Muslim women.

In an essay on colonial judgments on divorce amongst Muslims, Mitra Sharafi speculates that Hindu judges may have ruled in favor of Muslim wives under the influence of nationalist discourses that ‘portray[ed] Muslim men as conservative, hyper-religious and oppressive towards their wives and female relatives’. Sharafi recalls Spivak’s famous phrase, ‘white men saving brown women from brown men’. What we are seeing today is perhaps a case of ‘Hindu men saving Muslim women from Muslim men’, except, as lawyers Warisha and Shadan Farasat remind us, ‘Muslim women don’t need saving’.

It is worth noting that the conflict between group rights and women’s rights is not limited to Muslim women. In the coming months, the Indian Supreme Court is set to hear a case challenging the ban against women entering the Sabarimala temple. Article 25 will be debated here as well, particularly inasmuch as it reserves the legislative power to open Hindu religious institutions to ‘all classes of Hindus’.

The broader lessons for constitutional drafters are, firstly, that deferrals need to come with deadlines, otherwise they risk creating an unbreakable stalemate. Secondly, the Indian experience shows that subjugating fundamental rights to personal law both disempowers women and perpetuates colonial legal frameworks, with their concomitant social rifts and political fault lines. Constitutional drafters would be better off creating strong anti-discrimination guarantees, protecting individual liberties, and strengthening institutional vetoes, while creating uniform codes. Proponents of a UCC for India need to keep in mind, however, that a truly uniform code will also abolish the Hindu Undivided Family – a legal entity that presently affords Hindus considerable tax benefits.

Arundhati Katju is an Associate at the Center for the Study of Law and Culture, Columbia Law School. She practices law in New Delhi and is currently awaiting admission to the New York bar.