Mali’s promising constitutional reform process: Cementing peace through devolution of power

The constitutional reform process in Mali is central to efforts to settle and prevent recurrent conflicts and to accommodate the ethnic diversity of the nation. While there seems to be political and popular support to the reform process, divisions on substantive issues that surfaced in previous failed reform attempts may undermine the process – write judge Bamassa and Aboubacar.

Background

Mali has a rich constitutional tradition. The Constitution of the Empire of Mali, known as the Manden Charter, proclaimed in Kouroukan Fouga (Subdivision of Kangaba, region of Koulikoro, Mali) in 1236, is evidence of this historic reality. This Kouroukan Fouga Constitution, recognized in 2009 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, makes Mali one of the first civilizations to adopt a fundamental law (constitution) governing the organization and functioning of the institutions that compose it and, above all, guaranteeing the basic rights of human beings. It was therefore quite natural that Mali wrote a new constitution following its independence from colonial rule.

The independence Constitution of Mali, adopted in September 1960, constituted the First Republic. It set up a presidential system and a series of institutions, including a court dedicated to ensuring respect for constitutional supremacy. Nevertheless, the functions of this court were subsequently delegated to a special division of the Supreme Court. The independence constitution and the political regime it established were abrogated following the November 1968 military coup d’état, and replaced with a basic law on the organization of public powers. A constitution drafted under the military regime was adopted in a referendum on 2 June 1974. This Constitution, which marked the advent of the Second Republic, formalized the one-party system.

The totalitarian excesses of the military regime led to a popular uprising that culminated in the revolution of March 1991 and the fall of President Moussa Traore. The Fundamental Act No. 1 of 31 March 1991 introduced a democratic transition with the aim of rebuilding the state. Following a national conference that provided a crucial platform for consensus among political parties and civil associations on the transition to multiparty democracy and the drafting of a constitution, a new Constitution was adopted in a referendum in 1992, ushering in the Third Republic.

This Constitution, which is still in effect, installed the foundations for the rule of law and multi-party democracy in the contemporary history of the Republic of Mali. It affirms the visceral attachment of the Malian people to the essence of modern constitutionalism and rule of law, namely, the protection of fundamental rights. Furthermore, the Constitution establishes a dual executive shared between the President of the Republic and the Prime Minister and his cabinet, a unicameral Parliament embodied in the National Assembly, and an independent judiciary unified under the authority of the Supreme Court. The Constitution also establishes a Constitutional Court specifically charged with ensuring the protection of fundamental rights and controlling the constitutionality of laws prior to their entry into force.

Failed constitutional reform initiatives

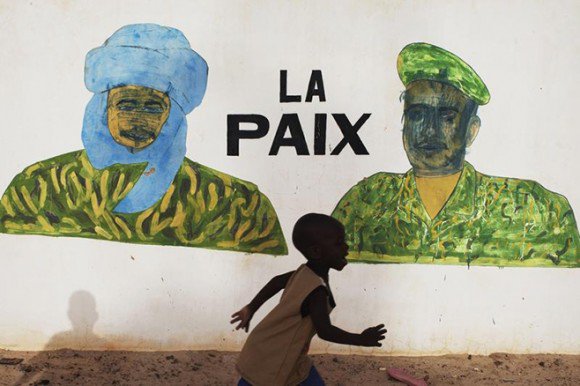

Ancient Greeks asked the wise Solon: ‘What is the best constitution?’, to which he responded, ‘Tell me first for what people and at what time’. These words, quoted by the former President of the French Republic Charles De Gaulle, affirm the idea that a constitution, as good as it might be, must evolve to fit the needs of the people and the circumstances of the time. Indeed, although the 1992 Constitution has never been amended, Malian political actors have on occasions attempted to change some aspects of it. The ongoing constitutional reform process, which is principally intended to incorporate relevant aspects of the peace agreement between the government and Tuareg rebels, is the most promising yet likely to lead to the first round of constitutional reforms.

In 2001, President Alpha Oumar Konare initiated several constitutional amendments. Nevertheless, the Constitutional Court declared the proposed amendments unconstitutional. The President amended fourteen articles of the draft amendment law after their examination in the National Assembly but before their planned submission to a referendum. This irregularity, contested by the opposition led at the time by the Le Rassemblement pour le Mali (RPM), the current ruling party, and noted by the Constitutional Court, led to the annulment of the amendment law.

Nearly a decade after this failure, President Amadou Toumani Toure launched a second constitutional review initiative. A committee of experts in charge of ‘thinking on the consolidation of democracy in Mali’ was established. The goal was to consider the possibility of amending the Constitution in order to address its democratic weaknesses and to modernize the institutions to adapt them to socio-political changes, in terms, for example, of funding political parties or building the capacity of the opposition against the president and his supporting majority in parliament.

The committee of experts was composed of lawyers, law professors, politicians and representatives of civil society, and was chaired by the then minister in charge of the reform of the state. In October 2008, the committee submitted its report to the President of the Republic. After the cabinet/government endorsed the report, the President submitted it to the National Assembly for adoption. On 2 August 2011, following discussions in legislative committees, the National Assembly approved the Constitutional Amendment Act by 141 votes in favor and three against. The vote attested to the wide political acceptance of the proposals.

Nevertheless, due to the high regard the current constitution enjoys owing to its participatory origins, some civil society activists and political groups demonstrated against the constitutional reforms under the motto: ‘Do not touch my Constitution’. The movement particularly protested the formation of a Senate as a second legislative chamber. Other controversial proposals included the removal of the referendum as the only mechanism to revise the constitution and the establishment of the possibility of constitutional amendment through parliament, and the removal of the Supreme Court and its replacement with a Court of Cassation (supreme body of the judiciary), a Council of State (the supreme body of the administrative order) and a Court of Auditors (supreme body of public accounts). The reforms also enhanced the powers of the president vis-à-vis the government and the parliament. In particular, it empowered the president to appoint and remove the prime minster and to define public policy. There were also less contentious proposals such as the empowerment of the Constitutional Court to review laws after their entry into force, the elimination of the High Council of Local Authorities, the easing of political party financing, and the establishment of a national agency in charge of organizing elections.

The proposed amendments were planned to be voted on in a national referendum to be held on the same day as the first round of presidential elections on 29 April 2012. Unfortunately, on 21 March 2012, a few weeks from the planned elections day, a military coup overthrew President Toure. The controversies surrounding the proposed constitutional reforms and the insurrection in Tuareg controlled regions contributed to the political crisis that laid the ground for the coup. The Tuareg rebels took advantage of the power vacuum, controlled large swaths of land in northern Mali and declared an independent state. The event immediately disrupted the electoral process and the constitutional referendum. The military group that overthrew the regime pronounced the dissolution of the 1992 Constitution and proclaimed a new fundamental law. Following international and regional pressure, Mali returned to constitutional order, which led to the cancellation of the act declaring the dissolution of the Constitution. Subsequently, the Constitution was reinstated and, in April 2012, Touré officially resigned, allowing the Constitutional Court to declare the presidency vacant, and to herald the transition.

Current constitutional reform initiative to cement peace

Following the signing of the Algiers Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation (peace agreement) with the Tuareg rebel groups in May and June 2013, presidential elections were held on 28 July (first round) and 11 August (second round) 2013, which was won by Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. The agreement contained compromises in particular concerning the establishment of regions with limited legislative and executive autonomy. Because the incorporation of the peace agreement requires some legislative and constitutional reforms, President Keita, in April 2016, established a committee of experts for the revision of the Constitution at the Ministry in charge of the Reform of the State. In July 2016, Mamadou Sissoko, former minister of justice, replaced Mamadou Ismael Konaté, who was appointed as the new minister of justice and human rights, as chair of the committee. In addition to incorporating relevant aspects of the peace agreement, the committee of experts has a broad mandate to propose draft revisions to promote the achievements of the previous attempts at constitutional revision, and to address any shortcomings in the Constitution.

The Prime Minister appointed the members of the committee at the proposal of the minister in charge of decentralization and state reforms, opposition groups as well as CSOs. The committee is composed of a president, experts, and two rapporteurs, and has an administrative support team. The 11 permanent experts and the two rapporteurs are all Malian nationals and include, among others, university professors, lawyers, and judges without party affiliation. Judges of the Constitutional Court were not considered for appointment as members of the committee as they may later have to decide on the acceptability of the proposed amendments. The members were selected solely for their competence, without regard to their ethnic affiliation, origin, gender, or religious believes. Nevertheless, the minister in charge of decentralization and state reforms, who made proposals for appointment, is a Tuareg, and three of the 11 members are women.

The committee is expected to produce a report and submit it to the President within six months of its formation, i.e. by the end of October 2016. The President may make changes to the draft and must seek the approval of the government/cabinet before forwarding the draft to parliament, which may make modifications to the draft. The draft will be submitted to a referendum if parliament approves it with a 2/3 majority. If approved in the referendum, a presidential decree will announce the coming into force of the constitution.

The committee has been conducting public hearings with government institutions, political parties, and civil society groups. Nevertheless, its proposals are not public. The exact scope of the reform proposals will therefore be unavailable until the official submission of the report. Nevertheless, a crucial aspect of the peace agreement includes the devolution of authority and changes to the presidential appointment of regional governors. The possible establishment of a senate, the restructuring/division of the Supreme Court into a Court of Auditors, a Council of State and a Court of Cassation, and other controversial issues in the earlier reform attempts are likely to resurface. While the reform process seems to enjoy broad political and popular support (there is nothing like the ‘Don’t touch my constitution’ movement), reactions may change once the details of the proposed reforms are revealed.

Sissoko Bamassa is a Member of the Constitutional Court of Mali. Guissé Aboubacar is a Technical Advisor to the Ministry of Investment Promotion and Private Sector.