Kenya’s failure to implement the two-third-gender rule: The prospect of an unconstitutional Parliament

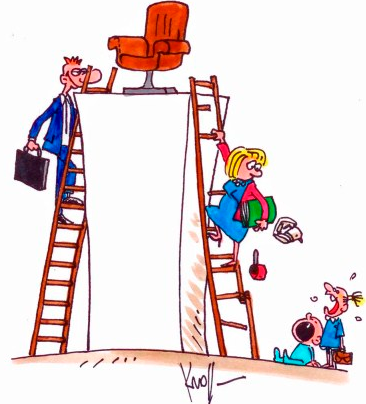

Despite the constitutional requirement to ensure gender balance in the National Assembly and the Senate, the number of women MPs remains low. Considering the advisory opinion of the Supreme Court, failure to achieve the required gender balance could potentially lead to the dissolution of the National Assembly and the Senate - writes Catherine Muyeka Mumma.

Background

On 28 April and 5 May 2016, the Kenyan National Assembly rejected the Constitution Amendment Bill (No. 4) of 2015, which sought to ensure that the National Assembly and the Senate would comprise of a membership that is not more than two-thirds of either gender.

The 2010 Kenyan Constitution entrenches the principle of equality and requires the state to adopt affirmative action programmes and policies to “redress any disadvantages suffered by individuals or groups because of past discrimination”. More specifically, it requires that elective and appointive bodies should be composed of “not more than two-thirds of either gender”. To give effect to this principle, the Constitution requires the provision of such number of special seats “necessary to ensure that not more than two thirds of the membership of the [county] assembly are of the same gender”. In contrast, while the constitution does not exclude the applicability of the two-third-gender principle to the National Assembly and the Senate, the provisions regulating the membership of the two houses do not have provisions to operationalize the principle in these houses.

In practice as well, the two houses of Parliament do not comply with the gender requirement. The National Assembly has a total of 349 members of whom 16 are women directly elected into the constituency seats, 47 women elected to the 47 county women representative seats, and five women among the 12 appointees representing the youth, persons with disabilities and workers. Elected women occupy 5.5% of the 290 constituency seats, while all the women make up 19.5% of the National Assembly. This is short of the two-third-gender ratio by 13.8%. Women constitute 26.9% of the Senate, which is also below the two-third rule. Eighteen of the 20 nominated senators are women. But the Senate does not have any elected woman.

The Supreme Court Advisory Opinion

The debate on the applicability of the two-third-gender principle to the two houses of Parliament began when the laws and regulations for guiding the first (2013) elections under the current constitution were being prepared. In particular, it was not clear whether the gender principle was a minimum that must be applied immediately and that any public elective body that would not meet the minimum gender quota would be unconstitutional. There was argument that, since the provisions on the membership of the two houses do not specifically require the two-third rule, the principle need not be applied immediately.

To avoid a possible constitutional crisis on the composition of the two houses after the 2013 general elections, and following extensive discussions among governmental and non-governmental stakeholders, the Attorney General (AG) sought the advisory opinion of the Supreme Court on whether the Constitution requires the implementation of the two-third-gender principle during the 2013 general elections. Key public institutions and non-state entities and individuals applied to and were admitted as “interested parties” and “Amicus Curiae”.

The Supreme Court, with a majority opinion with the Chief Justice dissenting, noted that the absence of a specific requirement in relation to the two houses of Parliament implied that, unlike in the case of county assemblies, the two-third-gender principle was amenable only to “progressive realization” in relation to the two houses of Parliament. It could not therefore be enforced immediately. Accordingly, the Court advised that, if measures necessary to crystalize the principle into an enforceable right were not taken before the 2013 elections, the principle would not be applicable to the said elections.

Nevertheless, bearing in mind the constitutional duty to promote the representation of marginalised groups in Parliament, and the five year constitutional deadline for the enactment of laws implementing the constitution, the Court advised that legislative measures giving effect to the two-third-gender principle in relation to the National Assembly and the Senate should be taken by 27 August 2015. The mechanisms for the implementation of the two-third-gender principle for the National Assembly and the Senate are yet to be established after Parliament exercised its constitutional power to extend the timeline by one year.

The Technical Working Group Formulae

Following the Supreme Court ruling, the AG constituted a technical working group (TWG) on 3 February 2014 to propose the most viable formula towards the realization of the two-third-gender rule. The TWG consisted of representatives from the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC); Ministry of Devolution and Planning (Directorate on Gender); the Commission on the Implementation of the Constitution; the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission; the Office of the Registrar of the Political Parties; National Assembly’s Committee on Justice and Legal Affairs (JLAC); Senate’s Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights; Kenya Women’s Parliamentary Association (KEWOPA); the Federation of Women Judges in Kenya; and the Commission on the Administration of Justice.

The TWG considered several options and discussed them with the AG, JLAC and the Senate Committee. After these considerations, the consensus was that the best option was to apply the constitutional mechanism set out in relation to county assemblies where women members are elected proportionately from party lists of qualifying political parties to meet the two-third-gender threshold. However, the members of JLAC decided not to adopt the proposed formula because, in the views of the committee, most members of Parliament would reject the proposal.

The “Chepkonga Bill”

The JLAC proposed that the TWG draft a constitutional amendment to the article on the principles of the electoral system to make the two-third-gender principle progressive, but the TWG declined. Consequently, the JLAC directed the Kenya Law Reform Commission to draft the amendment bill (“Chepkonga Bill”) instead of the TWG proposal.

The Committee hopes that by changing the wording in the constitution the responsibility of implementing the two-third-gender principle in the two houses of Parliament will stand postponed indefinitely and will put to rest the debate on the application of the principle in Parliament. The Bill was introduced in the National Assembly and Published in April 2015. Needless to say, women representatives and other stakeholders felt betrayed by and widely criticized the JLAC and called on the chairperson of this Committee to withdraw the Bill. The Chepkonga Bill was subjected to public consultation around the country where many stakeholders indicated their dissatisfaction with it and requested the Committee to withdraw it. The Committee did not withdraw it and the sponsor still plans to submit it for second reading now that the “Duale Bill” failed to pass.

The “Duale Bill”

Following the failure of the JLAC to adopt and work with the recommendations of the TWG and in line with the Supreme Court Advisory Opinion, and that of the AG to submit to Parliament the TWG Bill, the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness (CREAW) filed a suit in the Constitutional Court (The High Court). The CREAW sought to compel the AG and the Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution to discharge their constitutional duty to prepare the Bill implementing the two-third-gender principle and table it before Parliament for passing by the 27 August 2015 deadline.

The High Court directed the AG and the CIC to submit the Bill for the implementation of the two-third-gender principle to the National Assembly within 40 days of the ruling. The Attorney General finalized the draft developed by the TWG and submitted it to the National Assembly as a government Bill (“Duale Bill”). The House leader of Majority in the National Assembly, Hon. Aden Duale, published it on 24 July 2015. The Duale Bill seeks to introduce a clause to provide for the nomination, from party lists, of the number of members necessary to ensure that the membership of the National Assembly and the Senate meet the gender requirement. To ensure that this affirmative action is not permanent, the Bill limits the application of this mechanism to 20 years with a possibility of extension for a further 10 years if the minimum gender quota is not achieved. It also limits to two terms the period that one may be nominated under this mechanism. Each party list should also reflect regional and ethnic diversity and the beneficiaries should include young women and women with disabilities. To cater for concerns that party leaders may use their power to nominate close friends and relatives, the bill requires that elections to the party lists should be based on fair and competitive procedures.

The TWG led by the NGEC with the support of UN Women and CSOs, including KEWOPA, came together to strategize on how to lobby members of Parliament to pass the amendment. Consultations were held with different people including senior government officials, leaders of political parties and some members of Parliament. President Uhuru Kenyatta released a statement indicating his support for the Bill and asked all parliamentarians to attend Parliament and vote in support of the Bill. The leader of the main opposition party Hon. Raila Odinga also supported the amendment, including by discussing the proposal at one of his party retreats. All other party leaders in the opposition also indicated their support. Nevertheless, some parliamentarians indicated that they would not support the Bill on the ground that they did not want a large Parliament that would cost taxpayers a lot of money.

The second reading and voting for the Bill was on 28 April 2016. The Speaker of the National Assembly went out of his way to ensure that the House had at least the minimum number required to pass the Bill (233 members) before he called for the vote. The plan was to immediately call for the third reading if the Bill passed through the second reading. To mobilise for the vote on the two-third-gender principle, the Bill was put to second reading at the same time as another Constitutional Amendment Bill that was popular with MPs, as it sought to shield Parliament and county assemblies from judicial interference in matters under their consideration. Despite the efforts of KEWOPA and the Speaker, the National Assembly failed to pass the Bill. The Bill was submitted to a vote again on 5 May 2016 and was rejected. Although 178 members supported the Bill, the total number of members present was less than the required minimum to pass an amendment.

The prospect of an unconstitutional Parliament

As indicated earlier, the Supreme Court Advisory Opinion required Parliament to provide for mechanisms to implement the two-third-gender principle by 27 August 2015. The National Assembly extended the deadline by one year in line with its constitutional discretion to do so, but only once. According to the Court’s opinion, parliament is to be dissolved where it fails to enact legislation required by the constitution on a particular matter. It follows that the National Assembly and the Senate may be dissolved unless the mechanism to implement the gender principle is passed by 27 August 2016. Kenyan women are preparing to move the Court accordingly.

Some parliamentarians would reportedly like to pass the Chepkonga Bill to preclude any court action to send them home. Nevertheless, the Bill simply introduces the word “progressively” in certain constitutional provisions prescribing the gender principle. This addition cannot change the interpretation of the constitution since the Supreme Court has already interpreted the principle as being progressive. The passing of the Chepkonga Bill would therefore be an exercise in futility.

There are currently two viable possibilities for the implementation of the two-third-gender principle. First, the Senate can pass the “Sijeni Bill” and submit it to the National Assembly. This Bill largely replicates the Duale Bill, save the order of clauses and some small variations on the maximum time that beneficiaries may be members of Parliament through this mechanism. The second option is to submit the Duale Bill in the Senate, pass it, and bring it back to the National Assembly. In both cases, the period within which the mechanism for implementing this principle should be in place will lapse. Representatives of women are likely to move to court to order the President to dissolve Parliament to send a message on the importance of all institutions and persons respecting the constitution and the rule of law. While the courts will likely allow the legislative process to end before dissolving Parliament, particularly if the Senate passes the Sijeni Bill, the prospect of an unconstitutional Parliament remains a possibility.

Catherine Muyeka Mumma is a human rights lawyer and a former commissioner with the Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution and the Kenya National Commission on Human rights.