Irish constitutional debate on abortion and the resort to Citizens’ Assemblies

While the establishment of a Citizens’ Assembly embodies the central role of the people in constitutional reform, the strategy may have been used to avoid the responsibility of making difficult value decisions and a potential electoral backlash – writes Anne Marlborough.

Introduction

On 21 June 2016, the Irish Government called for a Citizens’ Assembly, a decision approved by resolutions of both the Dail and the Seanad (lower and upper houses of parliament) on 13 and 15 July respectively. While this appears, prima facie, to be an innovative use of a deliberative and participatory assembly to promote citizen engagement in constitutional reform, it has been heavily criticised as a cynical political tactic to remove the issue of abortion from parliamentary consideration. The Government is perceived as being unwilling to tackle the difficulties this controversial subject engenders.

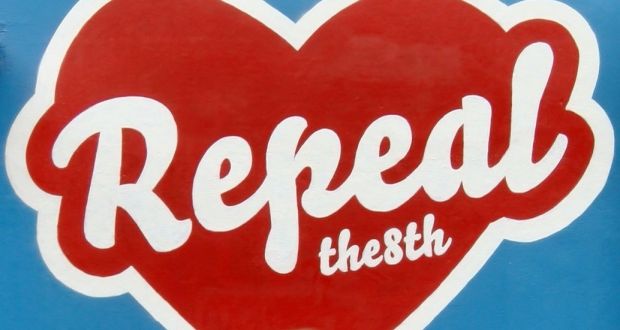

An agenda of five items has been allocated to the Citizens’ Assembly. The focus of this piece, and the most contentious of the themes, is the eighth amendment to the Constitution, i.e. the prohibition of abortion. Other crucial matters within the mandate of the Assembly are fixed-term parliaments; the manner in which referenda are held; responses to the challenges and opportunities of an ageing population; and Ireland’s role in tackling climate change.

Constitutional status of abortion

The eighth amendment to the Constitution, adopted in 1983, added an explicit guarantee of the right to life of the unborn to the pre-existing protection for personal rights. This provision remained without legislative regulation until the enactment of the 2013 Protection of Life during Pregnancy Act. This law provides for access to abortion on the single ground of risk to life of the mother. Burdensome certification requirements by multiple medical professionals must be complied with. Beyond that, attempts to procure or conduct abortions constitute a criminal offence. The strict legal regime has led to a situation where nine women and girls, on average, travel daily from Ireland to the United Kingdom for abortion. In 2015, the figure of those giving an Irish address was 3451.

The constitutional status of abortion has been controversial since 1983. The provision was amended twice (13th and 14th amendments in 1992) to ensure that it did not restrain the rights of pregnant women to travel or to access information. This was because the first judicial interpretation of the provision allowed for restraint on travel and information, where the right to life of the unborn was in jeopardy. The pro-life movement considers the constitutional protection of unborn life inadequate, as a mother may (in theory, though rarely in practice) lawfully solicit an abortion due to a risk to her life, which includes a risk arising from suicide. An attempt to remove the possibility was rejected in referenda in 1992 and, narrowly in 2002, but the goal of achieving same remains.

In contrast, pro-choice lobby groups seek the complete repeal of the eighth amendment. Several political parties, most significantly the Labour Party and Sinn Fein, espouse a pro-choice stance. The position of the parties within the governing coalition is more nuanced, with Fine Gael and Fine Fail both opposed to abortion on demand, but committed to respecting and facilitating the limited constitutional entitlements to abortion, while harbouring divided opinions within members of government. There is also a significant civil society movement advocating change, led by Amnesty International Ireland. Proposals as to the legislative regime to be installed range from permissive, of abortion on demand, to abortion in certain narrow circumstances, such as in the case of fatal foetal abnormality, or rape.

Political context

The political landscape within which the controversy on the constitutional status of abortion has been taking place has changed significantly since 1983. The original amendment was enacted due to a confluence of factors including a weak government and a strong Roman Catholic Church. The power of the Catholic Church has diminished significantly over time, with the evidence for this most clearly manifest in the outcome of the marriage equality referendum in 2015, when Ireland became the first state in which a plebiscite conferred constitutional status upon the right to marry for same-sex couples. The passage of the marriage equality referendum revitalised the campaign to repeal the eighth amendment.

There is also clear evidence that popular attitudes to abortion have changed since 1983. A recent poll indicated that a significant majority of Irish people support abortion in some cases. Similar support is also manifest in political circles during several parliamentary debates, in particular on access to abortion where the condition of the foetus is incompatible with life after birth. While a private members’ measure, the Fatal Foetal Abnormality Bill 2016, was defeated on 7 July, the content of the parliamentary debate indicated the existence of extensive support for law reform. The constitutional provision, however, was an obstacle to legislation, with the Attorney General advising that there could be no legislative change without constitutional change.

Constitutional change appears inevitable. Ireland’s current constitutional regime is unpopular domestically and is in violation of several of the state’s commitments under international law. The appetite of government for a referendum is, however, absent, so it remains uncertain when one will take place. A Citizens’ Assembly has been created, in what is widely viewed as a stalling tactic to avoid the holding of a referendum. This initiative is rejected by pro-choice actors, who are demanding an immediate referendum, and, more vehemently, by pro-life actors who allege that the outcome of the Assembly (that of recommending repeal) has been predetermined. The pro-life movement favours retention of the eighth amendment and rejects the conduct of any referendum on the matter.

The use of Citizens’ Assemblies in constitutional reform

Two deliberative and participatory initiatives on constitutional reform have been conducted in Ireland in the last decade. An entirely citizen-driven process, “We the Citizens”, was an academy-led civil society initiative in 2011, followed in 2012 by the creation of the Convention on the Constitution. The resort to citizen-driven reform processes has its origin in the widely-shared demand for political and constitutional reform arising from perceived political failures which contributed to the 2008 economic crisis. Government and parliament were seen to be too centralised and unaccountable, so a shift in power towards the citizen was mooted. The Labour Party spoke in April 2010 of the need for a people’s process, a constitutional convention, which would lead to parliamentary reform and devolution of power towards local democracy. Fianna Fail, in their 2011 election manifesto, proposed citizen involvement in constitutional reform, while the 2011-2016 programme for government of the Fine Gael and Labour government proposed the creation of the Convention on the Constitution with a mandate for constitutional review.

The 2012 Convention was an innovative entity comprised of 66 randomly-selected members of the public, 33 politicians from both north and south of the border, and an independent chairperson. While similar initiatives had functioned in Canada, the Netherlands and elsewhere, mainly in the context of non-constitutional electoral reforms, the Irish Convention was unique in bringing together both members of the public and serving politicians. This arrangement, viewed retrospectively, seems to have been mutually beneficial, with politicians and citizens complementing one another.

When established, there had been great scepticism as to the potential contribution of the Convention on the Constitution to constitutional reform. Critics had anticipated minimal or insignificant recommendations from an entity initially allocated a limited mandate (review of the voting age, and the length of the term-in-office of the president) as a means of sidelining contentious issues upon which the coalition partners could not agree. Civil society groups had raised concerns at the failure to include human rights groups within the Convention, while many commentators feared domination of citizen members by the politicians. The outcome was, however, widely perceived to be positive, with two of the recommendations having been put to referenda in May 2015, and the government accepting several others. The referendum on same-sex marriage was successful, while a proposal to lower the age of candidacy for the office of president was not carried. Political enthusiasm has, however, waned over time, and many of the 38 proposals are now being neglected, although they remain on the political agenda.

A similar initiative is now being born, in the form of the Citizens’ Assembly, a body conceived of in the programme for the current partnership government in May 2016. While this indicates that citizen deliberation and participation is becoming accepted as an element of the political process, it is arguable that it is being used as a vehicle to divert controversial and polarising issues away from mainstream political life. The Assembly differs significantly in composition from the Convention on the Constitution, in that it will be composed of 99 randomly-selected citizen members, without politicians, with an independent chairperson. A polling company will select the 99 people to be broadly representative of the electorate as a whole. Geographical and socio-economic distribution will be considered, but no attempt has been made to ensure that particular groups, such as women who have been denied abortions in Ireland, are included. The exclusion of politicians from the Assembly has been justified on the grounds that this will allow for greater public ownership and participation.

On 27 July, the Government appointed Ms. Justice Laffoy, a serving judge of the Supreme Court, to chair the Assembly, which will commence work in October, with an agreed lifetime of twelve months. Submissions will likely be invited from the public and from interested parties, as was the case for the Convention, which received thousands of submissions and conducted nine public meetings.

The passage through parliament of the motion to establish the Assembly was quite difficult, although it was ultimately achieved. While Sinn Fein, the Labour Party and several independents opposed the resolution, Fianna Fail, the partner in supporting the minority Fine Gael government, abstained on the vote, allowing it to be carried. The principal reasons for opposition were the desire to proceed directly to a referendum without further delay, the absence of politicians from the construct, the inclusion of abortion in the mandate, and the vague and uncertain nature of the other topics. Civil society is divided in response to the creation of this Assembly, with the pro-choice lobby unhappy with the delay engendered prior to conducting a referendum, but refraining from significant opposition to the entity, anticipating an outcome that will lead to repeal of the eighth amendment. The pro-life lobby, by contrast, has indicated the intention to challenge the Assembly and the review process, reflecting their opposition to any movement towards repeal, an outcome which they fear is gathering momentum.

The vanishing trick: Abdicating political responsibility

The referral of the constitutional status of abortion to the Citizens’ Assembly has been uniformly characterised, by political opinion outside government, by civil society, and by the commentariat, as an act of political cowardice, designed to delay debate on an issue which is long overdue for parliamentary consideration. The sole reason for the establishment of this Assembly is believed to be the removal of the eighth amendment from the political agenda, as Government is unwilling to grapple with this sensitive issue.

There is an important difference in the status of the proposals which will emanate from the Citizens’ Assembly (reached by a majority through secret ballot) compared to those from the previous Convention on the Constitution. In the earlier case, government was obliged to respond within four months to the proposals submitted to it. In this instance, the proposals will be sent to parliament, and then referred to a committee of both Houses, which committee will subsequently bring its conclusions back to the Houses for debate. While the Government will be then obliged to provide a response to recommendations, there is no temporal limit as to when this should take place. In neither instance was there any obligation that the proposals be accepted. Should a proposal be accepted, the government must then indicate a timeframe for the holding of a referendum, which is required for all constitutional amendments.

Constitution reform on abortion and international human rights law

With Ireland a state party to a plethora of international human rights instruments, the human rights system has played an important role in steering the debate on reform of the eighth amendment. The decision of the European Court of Human Rights propelled the enactment of the 2013Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act, albeit thirty years after the eighth amendment. On 9 June 2016, the UN Human Rights Committee, predictably reiterating previous criticisms of Ireland, delivered an opinion condemning Ireland for forcing the continuation of non-viable pregnancies. The decision of the Committee has added renewed impetus to the campaign to reform the eighth amendment.

Ireland is obliged to amend the Constitution to comply with its international human rights obligations. The creation of the Citizens’ Assembly does not, however, indicate that this is likely to happen anytime soon.

Conclusion

The decline of powerful traditional pro-life entities and changing societal attitudes, coupled with decisions of international human rights tribunals, have recently reignited the debate on reforming the eighth amendment. The issue remains socially and politically sensitive and divisive. The political class has pushed the debate back to the people. While the establishment of a Citizens’ Assembly embodies the central role of the people in constitutional reform, the strategy appears to have been deployed to postpone the responsibility of making difficult value decisions and to avoid a potential electoral backlash.

Beyond any negative construction of the abdication of political responsibility reflected in the creation of this Citizens’ Assembly, there is a positive, normative dimension to the creation of a second national deliberative entity. Political party manifestos for two successive general elections have contained competing and complementary articulations of such assembly, with the rationale for such proposals seemingly now beyond question. The success of the initial Convention on the Constitution in making recommendations, many of which were acclaimed and accepted, means that these assemblies are becoming part of standard practice in constitutional reform, particularly on socially controversial issues. As the demise of trust in politicians during the last decade persists, it seems likely that such assemblies will continue to be relied on to consider legal and political reform.

Anne Marlborough is an Irish lawyer working on the legal analysis of elections and democracy.Most recently she worked as legal expert on the EU EOM Myanmar 2015, and the Carter Center EOM to the Philippines 2016. She has a strong research interest in women and the law.