Electoral Crises, Peace Process with Taliban and Constitutional Reform in Afghanistan

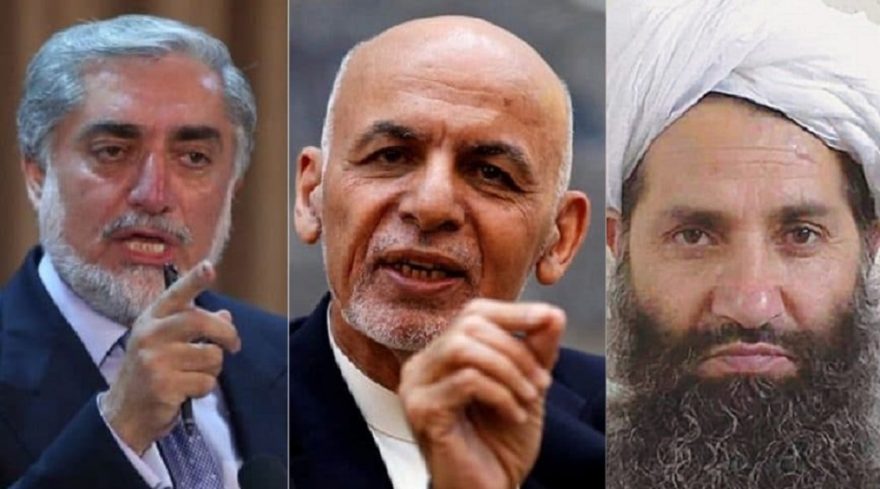

The political crisis over the results of the 2019 presidential elections and potential peace negotiations between ‘Afghan sides’ and the Taliban have once again elevated the constitutional reform agenda in Afghanistan. While there would apparently be no-red lines in the negotiations, a united front among the ‘Afghan sides’ is critical to preserve hard-won democratic values enshrined in the 2004 Constitution – write Shamshad Pasarlay and M. Basher Mobasher.

The 2004 Constitution of Afghanistan creates a highly centralised state with a powerful presidency. Initially, the drafters of the Constitution included a prime minister in the Constitution who would share executive power with the president to help accommodate the interests of Afghanistan’s diverse ethno-religious communities. Critics argued that a highly centralised state with extensive presidential powers could polarise post-Taliban Afghanistan and heighten ethnic rivalries in a deeply divided society. However, the former president, Hamid Karzai, opposed the drafters’ decision arguing that such a system would produce ‘instability in a highly factionali[s]ed and armed society’. Karzai ultimately forced the drafting committee to drop the prime minister and, instead, vested all executive power in the office of the president. As the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, most Pashtuns favour a centralised presidential system, while political elites from other groups tend to support a semi-presidential system and a decentralised state.

Recurrent political crises have highlighted shortcomings in the design of the executive branch.

Sixteen years and four presidential elections since the Constitution’s adoption have revealed that the critics may have been right. The system indeed intensified a ‘sense of winner-take-all politics’ in a post-conflict and heavily armed society by creating disgruntled electoral losers who refused to admit defeat and abandon their claims to the country’s most powerful political office. In 2014 and 2019, Afghanistan weathered severe political storms that almost split the nation.

The political disputes over the results of the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections highlighted the shortcomings in the 2004 Constitution’s design of the executive branch – a considerably powerful presidency. Although on both occasions Afghanistan’s leading politicians ended the political impasse by creating power sharing governments, the crises and the temporary patches underlined an urgent need for a systematic constitutional framework for power sharing that should reflect the country’s political realities. Afghanistan lost an opportunity to do precisely that in 2014, but the recent Agreement between Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah gives the country’s political elites another opportunity to remedy the flaws of the 2004 Constitution.

Afghanistan’s Divisive Elections

Since the fall of the Taliban and the adoption of the 2004 Constitution, Afghanistan has seen ten different elections: four parliamentary elections, four presidential elections, and two provincial council elections. Each of these elections was controversial, and none ‘went smoothly’. Afghanistan’s past two presidential elections were so divisive that they led to intense political crises threatening the country’s fragile stability. These electoral crises revealed several defects in the Constitution, including a centralised state, a powerful presidency, and flawed electoral institutions. In a tacit admission that the current system is problematic, power sharing agreements in 2014 and in 2020 promised to amend the Constitution to move Afghanistan to a mixed executive and implement electoral reform—reforms that only one party to the agreements, Abdullah and his team, favours.

In 2014, after a contested presidential election, a power sharing agreement between the two frontrunners, Ghani and Abdullah, established a National Unity Government (NUG) and provided that Ghani would be recognised as its president while Abdullah would be its Chief Executive Officer – a position not defined in the Constitution. Against the constitutional mandates, the Agreement authorised the President and the CEO to appoint half of the cabinet members each. The Agreement further required that all necessary steps should be taken for a constitutional amendment to create a position of a prime minister in the government.

Reform of the system of government and electoral regime is central to the power-sharing scheme.

However, the continued mistrust and disagreement between Ghani and Abdullah undermined the Agreement and the NUG that they formed. Ghani gradually began to use the Constitution against the Agreement to sideline his political opponents including Abdullah. Abdullah reviled Ghani’s moves, rejected some of his decisions, and called him ‘unfit’ for the presidency. By the end of its term in 2019, the NUG had failed to take the preliminary steps to amend the Constitution. Although a Multi-Dimensional Representation (MDR) electoral system was adopted to replace the Single Non-Transferrable Vote (SNTV) for parliamentary elections, its marks on elections and Afghan politics are yet to be seen because it has not been implemented. Similar to SNTV, MDR is another rarely adopted system that is less likely to help party development at least in the near future due to its candidate-centric voting feature. The other reform was the selection of nominees for the Independent Election Commission (IEC) by the 2019 presidential candidates, but this change failed to prevent electoral chaos during the 2019 presidential election.

The September 2019 presidential election was as controversial and divisive as the 2014 election. When the IEC announced the preliminary results in December 2019, it showed that Ghani won with more than 50 percent of the votes. Ghani’s main rival, Abdullah, rejected the IEC announcement and stated that the results had been engineered. Tensions increased when the IEC announced the final certified results on 18 February 2020 with Ghani as the winner. Abdullah again rejected the results and claimed that he was the rightful winner of the election. On 9 March 2020, both Ghani and Abdullah declared themselves president and were ‘sworn in’, and both pledged to form an ‘inclusive government’.

The power-sharing agreement requires the establishment of a commission to draft constitutional amendments.

The inauguration of two rival presidents paralyzed post-election Afghanistan at a critical juncture – a time when the US had signed a peace agreement with the Taliban with an assurance that negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government would start by 10 March 2020. Shortly thereafter, US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, travelled to Kabul to ‘broker’ a deal between Ghani and Abdullah, but he was unable to convince them to put their differences aside. Eventually, after much domestic and international pressure, Ghani and Abdullah signed another power sharing agreement similar to the NUG Agreement that would accommodate the interests of both presidential teams.

This power sharing Agreement, entitled as Political Agreement, forms a High Council for National Reconciliation which will be headed by Abdullah to take charge of the potential peace process. The Agreement provides that each side should appoint 50 percent of the cabinet ministers and provincial governors. Like the NUG Agreement, this Agreement also stresses the need for constitutional and electoral reform. It states that the government should take all necessary measures to hold district council elections in order to complete the quorum for the Constitutional Loya Jirga, grand assembly, to amend the Constitution. Although it does not provide a timeframe, the Agreement states that both Ghani and Abdullah should cooperate in appointing a commission to draft amendments to the Constitution to ‘change the structure of the government’ and implement electoral reforms.

Negotiation with the Taliban

The need for constitutional reform comes amid ongoing peace negotiation efforts with the Taliban. On 29 February 2020, the US and Taliban representatives signed a landmark deal which opened the door for direct negotiations between the Taliban and the ‘Afghan sides’. In a step to build confidence between the Taliban and the Afghan government, the Deal mandated that by 10 March 2020 the Afghan government would release up to 5,000 Taliban prisoners, and the Taliban would release 1,000 Afghan government prisoners. After an initial setback, the government released a significant number of Taliban prisoners, but the intra-Afghan talks are yet to begin.

If the Taliban and the Afghan government sit down to negotiate a political settlement of the conflict, changes to the Constitution are likely to be central to the process. The Taliban played no role in the drafting of the 2004 Constitution and reject the document. They complain that the Constitution lacks legitimacy because it had been ‘written under the shadows of [U.S.] B-52 aircrafts’. Taliban also claim that the Constitution is not ‘Islamic’ and that an Islamic constitution would be one drafted by ‘Islamic scholars’.

The Taliban’s preferred system of Islamic governance is in deep tension with the system defined in the Constitution.

On a number of occasions, the Taliban have declared that they would only be satisfied with an Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan without providing any details about how it would look like. Many inside and outside Afghanistan fear that the Taliban might restore the repressive Islamic Emirate that they established in the late 1990s. The Taliban have publicly declared that their return to politics ‘will not be in the same harsh way as it was in 1996’. However, they apparently prefer a system in which an Amir Al-Mominin (commander of the faithful) would wield the ‘highest authority’. A council of religious scholars would elect and advise the Amir. The Amir’s consent would be required for any government decisions to be implemented.

The Taliban’s preferred system of Islamic governance is in deep tension with the system defined in the Constitution where a president, whose authorities are not unconditional, is directly elected by the people. The Afghan sides stand firmly on this system and state that the democratic republican system is non-negotiable. In order to avoid a deadlock, the Taliban have recently indicated that they want to ‘build an Islamic system’, not necessarily an Islamic Emirate – something that is reflected in the US-Taliban Deal. The monumental task of how such an ‘Islamic system’ would look like and what powers its head would exercise will be discussed in the intra-Afghan talks.

It remains unclear whether the Taliban want a significant constitutional amendment or an entirely new constitution to accommodate their demands. Afghan political elites are committed to the 2004 Constitution, but they agree that amendments are needed to address issues of equitable access to power. The Taliban, however, might be inclined to draft a new constitution because mere constitutional amendments are unlikely to meet all their demands. The Taliban have long insisted that a legitimate constitution could only be drafted by religious scholars – arguably those who share the Taliban’s interpretation of religion – a demand that might necessitate drafting a new constitution.

Concluding Remarks

Pressure is mounting on the Afghan government to address the problems in the Constitution, notably the failure to accommodate diverse ethno-religious interests. In 2020, Afghanistan dodged yet another bullet by signing a power sharing agreement and agreeing that the Constitution should be amended to restructure the government, break the hold of the president on power, reform the electoral system, and empower local governments. The Agreement, however, does not necessarily guarantee any reform by itself, as the failures of the 2014 NUG Agreement attest to.

Ghani is likely to be reluctant to take the necessary measures towards constitutional amendment. Although he is serving his last term as president, and therefore does not have personal interest, he remains committed to the current presidential system, partly because he would not want to alienate his Pashtun support base, who favour a centralised state with a presidential system. Most Pashtuns believe that a popular Pashtun candidate with two vice-presidential candidates from non-Pashtun groups might have a realistic chance to win the presidency for the foreseeable future.

Although Ghani is serving his last term as president, he remains committed to the current presidential system.

Abdullah and his team, on the other hand, have repeatedly pushed for a mixed executive and a party-oriented electoral system. Nevertheless, with Ghani unable to run again, Abdullah may find his interests best served in maintaining the presidential system in hopes that he might win the prize in the next presidential elections. However, Abdullah’s main support comes from non-Pashtun ethnic groups who have long demanded to include a prime minister’s position in the government in hopes that they might control that institution.

What might affect the political calculations towards both the electoral and political reforms this time is a potential peace deal with the Taliban. Nonetheless, the Taliban remain remarkably ambiguous about what exactly they want, and it is hard to predict the direction of the restructuring of constitutional institutions.

While including the Taliban in the process is vital to sustain constitutional reform, their demands and potentially high influence necessitates caution. It is important that the parties, the Taliban and the Afghan government, conclude a comprehensive peace agreement that binds them to a consensual and inclusive process. Without a peace agreement, it is likely that parties might resort to violence as their main leverage during constitutional negotiations, thereby turning the constitutional arena to another zone of conflict. While including certain non-negotiable questions, especially women and minority rights, might be preferable, both sides have indicated that they want to enter the negotiations with ‘no red lines’. In particular, the Taliban seem unwilling to exclude any fundamental questions about the nature of the state and its ideology from their agenda.

The recent elections and informal negotiations between the Taliban and the ‘Afghan sides’ have revealed that the latter are notoriously fragmented, void of political agenda, and focused on power patronage. Taliban, by contrast, have been highly cohesive and ideologically unwavering. With their current forms and politics, Taliban might have an advantage in any process of constitutional reform. It is thus important for the Afghan sides to put their differences aside and present a united position in the potential talks to preserve the democratic values enshrined in the 2004 Constitution.

Shamshad Pasarlay is a lecturer at Herat University School of Law in Afghanistan and M. Basher Mobasher is an assistant professor of Political Science at the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF).