DRC’s Constitutional Court: Broken shield in overseeing the executive in emergencies?

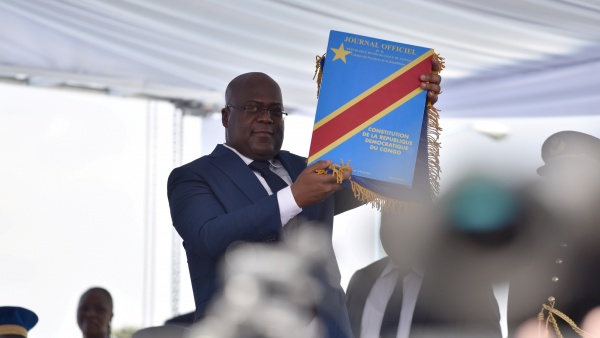

President Felix Tshisekedi’s declaration of a state of emergency to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic raised controversies on whether Congressional authorisation was necessary. Concern over presidential impeachment by Congress, controlled by his coalition partner former President Joseph Kabila, triggered Tshisekedi to refer the matter to the Constitutional Court. The Court’s findings may have kept the fragile coalition of convenience alive but failed to safeguard fundamental rights – writes Trésor M. Makunya.

The National Institute for Biomedical Research (INRB) confirmed the first case of Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) on 10 March 2020. By 18 March, 14 citizens tested positive prompting President Felix Tshisekedi to announce measures aimed at ‘flattening the curve’ and preventing the pandemic from reaching the provinces from Kinshasa (the capital). The government closed schools and churches, and prohibited sports events. It also closed borders and halted movement from and to Kinshasa. The declaration of the state of emergency on 24 March enabled the government, both at the national and provincial levels, to restrict fundamental rights, the most severe infringements being the partial lockdown in Kinshasa, Goma and Lubumbashi.

The emergency declaration sparked political and constitutional criticism partly because Congress (joint siting of the National Assembly and Senate) did not authorise the President to declare such emergency. Facing a potential threat of impeachment, the President approached the Constitutional Court to review the constitutional validity of the declaration and measures adopted under it, which the Court approved of.

Framework for declaring states of emergency

The 20 March state of emergency is the first ever under the 2006 DRC Constitution. The lack of experience was apparent in the controversy over the exact procedure in issuing emergencies, particularly on the requirement for the President to coordinate with the Prime Minster and the presidents of the two legislative houses, and on review by the Constitutional Court. The lack of clarity and presidential vulnerability to impeachment led to the involvement of the Constitutional Court, which helped clarify the process. The president ultimately consulted and received the approval the Prime Minister and presidents of the two houses.

The Constitution authorises the President to declare states of emergency ‘[w]hen grave circumstances constitute a present threat to the independence or the integrity of the national territory or when they provoke the disruption of the proper functioning of the institutions’. The Constitution seems to empower the President to assess the circumstances that justify a state of emergency but requires consultation with the Prime Minister and presidents of the two legislative houses. The form of consultation is unclear, particularly on whether they should approve proposed emergency declaration or merely be informed of it. The Constitution requires the two legislative houses to pass legislation to regulate modalities of application of states of emergency, which is yet to happen. Consequently, the exact role of the two houses in preventing arbitrary emergency declarations is unsettled.

The legislative power to terminate emergencies is an important feature of the 2006 Constitution limiting presidential powers and discretion.

Under the Constitution, the President must officially inform the nation about a declaration, which is valid for 30 days. The National Assembly and the Senate may renew an emergency declaration for 15 days at a time based on referral of the President following deliberation in the Council of Ministers. The two houses may adopt a law terminating at any time a state of emergency. The legislative power to terminate is an important feature of the 2006 Constitution limiting presidential powers and discretion. The two houses have prolonged the state of emergency three times.

Crucially, article 119(2) of the Constitution requires Congressional ‘authorisation’ of declarations of states of emergency. Despite this provision, the President did not seek an authorisation in issuing the 20 March declaration. The acting chairperson of the President’s political party argued this was not needed based on an isolated reading of article 85 as granting him a carte blanche to declare states of emergency.

Threats of presidential impeachment have been recurrent.

Nevertheless, there is no contradiction between articles 85 and 119(2). Whilst the former determines executive powers to declare states of emergency, the latter institutes checks and balances. The requirement for legislative authorisation seeks to prevent the likes of untimely and unrestricted state of emergency former President Mobutu Sese Seko resorted to during the last decade of his 32 years-reign.

Following the controversy over Congressional authorisation, the President was concerned that Congress could initiate presidential impeachment on grounds of violation of the Constitution. This panic emanates from the fact that the president’s party is a small minority in Congress. Although he entered into a coalition of convenience with former President Kabila following contested presidential elections in 2019, threats of impeachment have been recurrent. Under the Constitution, two-thirds of all members of Congress could initiate presidential impeachment before the Constitutional Court. The majority of members of Congress belong to Kabila’s coalition. It is perhaps to preclude this possibility that the President approached the Constitutional Court to rule on the emergency declaration.

A broken shield? The Constitutional Court ruling on emergency measures

The President approached the Constitutional Court to review the constitutional validity of the emergency declaration and related measures 15 days after it was proclaimed. This referral is required under the Constitution and the Constitutional Court Act and ensures equilibrium among the arms of government and safeguards fundamental rights and freedoms.

While the President is not required to refer an emergency declaration to the Court, referral of ordinances giving effect to the declaration is mandatory. There must exist two types of ordinances, one declaring states of emergency (article 85) and the other on emergency measures after deliberation in the Council of Ministers (article 145). However, the president did not follow this logic and adopted one ordinance containing the declaration and the emergency measures.

The Court unanimously approved the emergency declaration.

Be that as it may, in a unanimous decision, the Court ruled the declaration was constitutional as formal requirements were respected and that COVID-19 related restrictions were aimed at preserving the right to life, health and to a healthy environment. Because the drafters of the Constitution did not define the nature of circumstances which may spur states of emergency, the Court ruled that the President could choose between declaring a state of emergency with the approval of Congress (under article 119(2)) or without Congress’ intervention (under article 85).

The Court essentially found that conditions under the two provisions could be applied alternatively and not cumulatively, depending on the circumstances. The legislative houses had suspended their sessions due to COVID-19 before the emergency declaration. The Court perhaps assumed that, in view of the circumstances, it was absurd for the President to seek Congressional authorisation.

The Court’s decisions of 2007, 2019 and 2020 on the need for Congressional authorisation of emergencies are confusing.

The Court’s ruling raises more questions than it answers. The ruling departs from two earlier decisions without explaining the reversal. When the Supreme Court (acting as the Constitutional Court) reviewed the Congress Standing Orders in 2007, it confirmed that the President did not require Congressional authorisation to declare states of emergency. In 2019, the newly established Congress approached the Constitutional Court to review the Orders which contained a provision requiring the President to obtain authorisation before declaring states of emergency. This time, the Orders were declared valid.

In finding that the President does not need Congressional authorisation in the current case, the Court effectively reversed its 2019 ruling without explanation. In the absence of appropriate reasoning to clarify the relationship among the 2007, 2019 and 2020 decisions, these reversals could sabotage the Court’s authority and undermine its legitimacy.

Endangering non-derogable rights

In addition to the lack of explanation for the reversal of its past judgments, the Court failed to clarify the constitutionality of presidential measures restricting numerous rights, despite constantly claiming it was the ‘gatekeeper’ of fundamental rights and freedoms. This sets a bad precedence as it gives the impression that executive authorities can restrict rights without proper legal basis using health, or other exceptional circumstances, as an excuse.

The 2006 DRC Constitution includes a list of rights and ‘principles’ - the right to life, prohibition of torture, slavery, the freedom of thought, conscious and religion among others - that cannot be derogated from even in exceptional circumstances. It also prohibits constitutional amendments during exceptional circumstances and any amendments that ‘reduce’ the scope of fundamental rights and freedoms.

Under the Constitution, ordinances giving effect to states of emergencies must be reviewed by the Court before their implementation.

To ensure the effective protection of these rights, the Constitution requires that ordinances necessary to tackle emergencies be taken by the President after deliberation in the Council of Ministers. The ordinances must after their official signature automatically be submitted to the Constitutional Court to determine whether they derogate from the Constitution. Despite this constitutional requirement, the measures were not submitted to the Court, and the case reached there only following the controversy over Congressional authorisation. But even then, the Court failed to properly scrutinize the impact on fundamental rights.

The normative protection of fundamental rights during exceptional circumstances is robust but needs clarification, for example, on the nature and scope of the right to the non-derogable freedom of religion. Apart from the freedom to ‘have or adopt a religion’, does the Constitution envisage the right to include the ‘freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching’? If so, can it be logically concluded that a measure suspending church gatherings violates the Constitution?

The decision of the Court raises more fears than hopes for the future of constitutionalism in the country.

Similarly, partial and temporary lockdown impacted economic activities of many citizens who could not work. How can the right to free enterprise, to work and to food security be reconciled with government measures?

The fact that the President announced some of these measures through a television message on 18 March before he declared the state of emergency raises additional questions about their conformity with the Constitution and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter). Both the Constitution and the African Charter permit restrictions when they are provided by ‘the law’ and a television message is anything but a ‘law’.

The Constitutional Court thus missed an opportunity to lay down a robust framework for the exercise of rights and political power during exceptional circumstances. Such clarification would have been useful considering the absence of specific legislation regulating states of emergency. Its approach was formalistic, timid and human rights unfriendly, raising more fears than hopes for the future of constitutionalism in the country.

Trésor M. Makunya is an Advocate of the Court of Appeal of North-Kivu (DRC), a Visiting Lecturer at the Notre Dame University of Tanganyika (DRC) as well as a Doctoral Candidate and Academic Associate, Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria.