Benin’s fourth failed constitutional reform effort: The decisive legacy of participatory processes

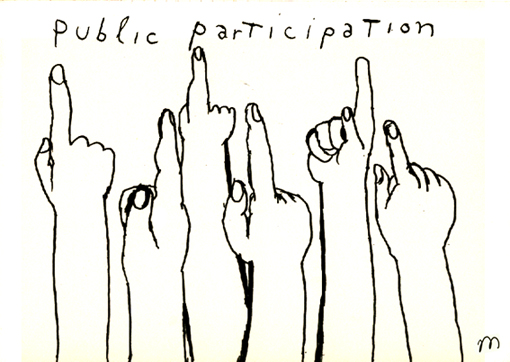

Although they addressed crucial issues in Benin’s constitutional experience, parliament rejected President Talon’s proposed amendments, principally due to concerns regarding the hasty and nontransparent drafting process, combined with the fundamental nature of some of the targeted provisions. The experience indicates that a legacy of broadly inclusive and participatory processes in the making of the original constitution could establish expectations of similar levels of participation for significant amendments among the public and other stakeholders, including crucial veto players, such as courts – writes Dr Adjolohoun.

Background to the making of the 1990 Constitution

In March 2017, Benin’s National Assembly declined to consider an executive bill to introduce 15 and to amend 43 of the 160 provisions of the country’s 27-year old, thus-far untouched 1990 Constitution. This was the fourth failed attempt at amending the constitution since 2004, raising the question of whether the fundamental law will ever be amended.

From its independence in 1960 until 1989, Benin experienced political instability with no less than eight coups, and ten constitutions and ten presidents only between 1963 and 1972, earning itself the title ‘the sick child of Africa’. While the 1972 coup brought about stability, it came with a one-party dictatorship. In 1989, against the backdrop of the fall of the Berlin Wall and a regional financial crisis, domestic social forces reverted to indefinite strikes and protests that led to the first successful national conference in Africa. Gathered in that conference, the forces vives de la nation opted for a liberal constitution and a Constitutional Court with extensive powers.

The first debate on amending the constitution emerged in 2004 with the ‘Do Not Touch My Constitution’ civil society campaign in response to perceived wishes to remove presidential term limits, but materialized formally in 2006 when Members of Parliament (MPs) hurriedly passed an amendment extending their term from four to five years. Although the constitution allows amendments through parliament or referendum, the Constitutional Court declared the amendment unconstitutional. The Court held that ‘national consensus’ animated the National Conference which gave birth to the constitution, and any amendment should therefore uphold that principle through a participatory and open process.

State of the amendment discourse before 2017

Before and immediately after the 2006 national consensus decision, the general approach to amendment was ‘Do Not Touch’ as attempts were viewed as ‘opportunistic’, that is aimed at allowing incumbent presidents to run for a third term, against the two five-year term constitutional limit. All attempts failed due to pressure mainly from civil society and political opposition. In 2006, former President Mathieu Kerekou faced opposition when his ministers proposed to extend his term and to merge parliamentary and presidential elections due to resource constraints. Notably, in 2009, when President Boni Yayi’s government introduced an amendment bill to ‘correct’ the imperfections arising from two decades of practice, the process was opposed for lacking openness and being opportunistic, although it preserved critical provisions such as presidential term limit. In 2011, while reviewing a Referendum Bill, the Constitutional Court recognised as ‘unamendable’ the provisions on presidential term and age limits and the presidential system of government, in addition to the expressly protected provisions on territorial integrity, the republican form and secular nature of the state. Commentators, such as Komla Dodzi Kokoroko, perceived this move as abridging the constituent power of the people and their representatives since the Court’s position amounted to either sticking to the current constitution, or requiring a new constitution if these three implied unamendable aspects were to be tampered with.

Subsequent to these failed attempts and jurisprudential moves by the Constitutional Court, the amendment debate inevitably moved from opportunity to substance – in reference mainly to presidential term limits, and momentum, as the public believed changes proposed in early years of a new presidential term are less likely to carry opportunistic motives.

Such was the amendment landscape until cotton magnate Patrice Talon placed constitutional revision on the top of his 2016 electoral campaign agenda in a bid to, among others, prevent any president from replicating the perceived moves of Boni Yayi to extend his terms.

The March 2017 proposed amendments: Consensus and controversy

There are two important aspects of the failed March 2017 attempt to amend the constitution. The first is procedural, and the second substantive. Concerns over the participatory nature of the amendment process and suspicion among the public and some MPs about parts of the substantive proposals, born out of the ‘Do Not Touch’ attitude and attempts of earlier presidents, led to a numerically weak yet politically strong rejection of the proposed reforms.

On Procedure: How public should ‘public consultations’ be?

During the campaign and on several occasions after he took power, President Talon publicly restated his promise to amend the constitution by late 2016, which was within eight months of assuming power. Furthermore, while launching the Political Reforms Commission, an organ established unilaterally by the president to lead the amendment process, he restated that he will allow as broad consultations as possible in the amendment process. Many therefore expected consultations to take place before mid-2016, but there was no shared understanding of what ‘consultations’ would actually involve.

For the government, ‘popular consultations’ meant involving representatives of major stakeholders from previous amendment processes. Participation of renowned legal scholars, lawyers, historians, political scientists and sociologists, many being members of previous reform commissions, and leaders of the former ruling coalition in the Reforms Commission attest to that perception. On the other hand, the public and a number of relevant stakeholders, including an academic and former minister of justice, the Constitutional Court (informally), trade union leaders, civil society groups, and political parties, expected that consultations would involve wider popular dissemination of the proposed amendments well ahead of any political process, specifically prior to the consideration vote in parliament, and possibly before a potential referendum. So, the Minister of Justice and Head of the Reform Commission stirred public outrage when he announced, in mid-March 2017, that ‘March will be the month of amendment of the Constitution’. His statements were understood as meaning that the amendment would be completed within two weeks, and therefore without wider popular consultations.

Opposition to the bid mounted as government ignored calls to publicize the proposed amendments, which built greater suspicion about the intention and contents of the proposals. Obviously, the ‘Do Not Touch’ attitude and the national consensus decision further fueled the public rejection. Even voices from within parliament, including those supporting the ruling coalition, lamented that they had not been privy to the framing of the proposed amendments. The government responded that it was not legally compelled to make the proposals public before their formal submission to parliament, after which consultations would follow.

Fear of opening a Pandora’s Box

When the amendments eventually reached parliament, civil society and political leaders, who were already on the defensive, launched a wide media confrontation and demonstrations at the National Assembly demanding that MPs block the consideration. Any amendment requires a double vote of three-quarters (63 out of 83 MPs) to ‘agree to the idea of the amendment’ (consideration vote), and four-fifths (67 MPs) to approve the actual amendments in parliament (or alternatively a referendum).

The procedure in parliament unfolded in three stages. First, the President of the Republic requested an expedited procedure during an extraordinary parliamentary session, which stirred greater debate and suspicion among the public about the intention to hasten the process and the unpopular nature of the contents of the bill. The request for that specific type of procedure therefore led to demands from the public that MPs should block the process altogether, and was unanimously rejected by parliament. Second, the Parliamentary Law Commission held its sessions and drafted a report in support of the consideration of the bill. Meanwhile, the government provided funds to MPs from all political sides to ‘conduct’ ‘sensitization’ visits (‘field consultations’), apparently in a bid to curb the discontent expressed among civil society groups and political elites, and to obtain as much support as possible directly from local constituencies.

When the report was tabled before parliament, it did not receive the strong backing the government anticipated following the positive Commission report and the last minute ‘field consultations’. Despite calls from within and outside parliament that MPs should agree to consider the bill in order to debate each amendment and to reflect their opposition by changing the proposed amendments, the debate moved from a vote to determine if a substantive consideration should follow, to the actual substance of the proposed amendments, in particular changes attracting strong public criticism, such as presidential term limit and immunity for MPs and the executive. In the end, only 60 MPs (three fewer than required) agreed to consider the bill, thereby ending the process. The 22 MPs who voted against the proposal and the one who abstained blocked the entire process for fear of opening a Pandora’s Box which they believed they may lack the political ability to control.

Substance of the Bill: Refurbished Edifice or New Castle?

The major question raised by the proposed bill coincides with the very reasons for its rejection: was the bill for a toilettage – cleaning up – of the constitution, or was it looking to make a new constitution? Overall, the proposed changes would have affected 58 of the current 160 provisions. While only 15 of these were new provisions, the overall change targeted about one-third of the text.

Beyond the controversy on the scope of the proposed changes, the bill addressed some of the major and recurring concerns facing Benin’s constitutional debates in the past two decades. In particular, the proposed amendments would have strengthened the separation of powers and judicial independence. Specifically, the amendments sough to largely insulate the Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature – the equivalent of a judicial service commission – from executive interference by excluding the President of the Republic and the minister of justice from the composition of the Council, as is currently the case. Moreover, the amendments would have reduced the direct role of the president and parliament in the process of appointment of members of the Constitutional Court, although they simultaneously rescinded some significant powers of the Court, such as the suo motu monitoring and declaration of outcomes of presidential and parliamentary elections. In addition, the Haute Cour de Justice, the body responsible for trying presidents and ministers, would have been depoliticized and turned into an actual court composed exclusively of judges, thereby excluding politicians, who currently sit in it.

Furthermore, the reforms would have enhanced the political representation of women by requiring political parties to enlist women for elective positions, although this does not apply to appointed positions and no specific quota was established.

The proposed amendments would also have addressed the proliferation of political parties, which has earned Benin the name: ‘the country of a thousand political parties’. Only political parties that obtain at least 10 per cent of the votes in any general elections would have obtained seats, while a share of one-fifth of parliamentary seats would have been required to be eligible for public funds to political parties. As an additional reform, national and local, but not presidential, elections would have been merged. The aim was to encourage the conflation of the current list of about 300 existing political entities to around two or three major coalitions.

Lastly, the changes proposed would have abolished the death penalty, and enhanced the independence of the media regulating authority, with media professionals appointing the majority of its members who have been appointed so far by the executive and parliament.

Despite these crucial issues, parliament rejected the proposals before they even reached the formal substantive deliberation stage. What proved fatal for stakeholders was partly the formula adopted to address the said issues, and partly the controversy regarding the proposed enhancement of immunity of parliamentarians and ministers before, during and after their time in office. Also controversial was the desire to turn a personal vow to run only for a single term into a constitutional prohibition on re-election. Considering the particular significance of the issue of term limits, it is discussed below.

Presidential term limit: From personal vow to constitutional policy

Here is probably one of the most important proposals that explains the controversy over the entire reform process. During his electoral campaign, President Talon consistently pledged to run for only one five-year term while the constitution allows two terms. Such pledge is laudable in the recent African context characterized by abuse of term limits by incumbents. What attracted less praise was the desire to superimpose a personal pledge onto the people’s will. The proposed provisions sought to extend the current five-year term by one year and to reduce the number of terms from two to one. Public opposition to this bid was stronger as the change would have tampered with a key pillar of the national consensus edifice. As alluded to earlier, the Constitutional Court has carved both the duration and number of terms in the stone of national consensus and prevented even the original constituent, that is the people, from making any change thereto, except by adopting a new constitution. To many stakeholders, including some MPs concerned about opening a Pandora’s Box, the very idea of this change made the bill unacceptable, even at the consideration vote level.

The strong opposition to this proposal was compounded by the concluding section of the bill, which stated that ‘the present constitutional bill does not seek to establish a new constitution and does not enact a new republic …’. This conclusion was perceived as seeking to conceal a hidden agenda, that is to enact a new republic in which constitutional clocks will be reset and the political pledge to term limit will become meaningless, as was the case in the Senegalese 2012 presidential election. The President’s insistence to constitutionalize a personal pledge is also questionable as it came in response to his predecessor’s overall governance and particularly the latter’s attempt to run for a third term. The related apprehension is whether the framing of such an important law as the constitution, and as critical provisions as that on term limit, should be based on the behavior of a particular leader, whatever it may be.

Concluding remarks and the way forward

The rejection of the proposed amendments was surprising for an independent candidate who won the presidential election just a year ago with support from major political quarters. In fact, parliament declined to even consider the proposed changes, though it would have had ample discretion to accept or reject them after a substantive debate. While a combination of factors explains the rejection, the fact that the proposals failed at the first stage before formal substantive discussions seems to suggest that the reluctance to consult the broader public, and the suspicions it engendered including among the decisive minority of MPs, played a major role. Although there were significant concerns regarding some of the substantive issues, which strengthened the suspicion and impetus to reject the reforms at the earliest possible stage, they could have been addressed at the substantive discussion stage.

In an initial reaction to the rejection, the president stated that ‘it is over with the issue of amendment; it is over with the single term; all these are behind me’. With specific reference to his promise to run for a single term, he added: ‘I will advise in 2021’. However, in a subsequent interview, he stated that the rejection was political and that he will make a new attempt when ‘the political environment will be more conducive’. These inconsistent statements reflect the dilemma that the president caused for himself by pledging for a single term in the beginning.

Whether the 1990 constitution will be amended, and when, remains anyone’s guess. Nevertheless, the latest experience affirms the value of a transparent and participatory amendment process to push through even substantively desirable constitutional amendments enhancing the separation of powers. Most importantly, broadly representative, inclusive, and participatory processes in the making of the original constitution could establish expectations among the public and stakeholders, and crucial veto players, such as courts, of similar levels of participation for significant reforms, especially when the changes target crucial constitutional provisions.

Dr Sègnonna Horace Adjolohoun is a Beninese lawyer with specialization in human rights and constitutionalism in Africa. He currently works as Principal Legal Officer at the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and is a Visiting Professor of Human Rights Law and Comparative Constitutional Law at the Central European University, Department of Legal Studies.